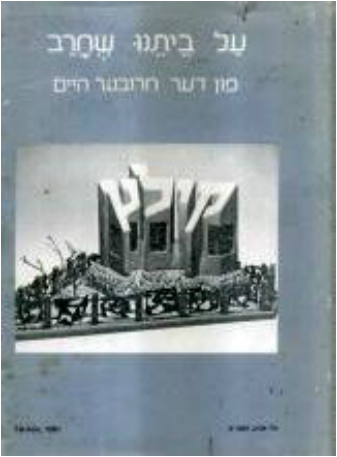

Front cover of yizker bukh, Al betenu she-harav—Fun der khorever heym [About our house which was devastated] (http://goo.gl/naZjA3, accessed 5-22-16). Front cover of yizker bukh, Al betenu she-harav—Fun der khorever heym [About our house which was devastated] (http://goo.gl/naZjA3, accessed 5-22-16). Lately, I have been thinking a great deal about landsmanshaftn and yizker bikher, both of which I will define, shortly. In the last month or so, alone, I have had more than half a dozen meetings and correspondences with clients and acquaintances to discuss the subject of landsmanshaftn in Chicago and New York City, and to translate excerpts of landsmanshaft minutes’ books – handwritten in Yiddish in the 1940s – from a landsmanshaft. This, and my own personal history vis-à-vis landsmanshaftn and yizker bikher prompted me to write this blog about those two very much intertwined subjects. A landsman [pl. landsmen] is Yiddish for “kinsman” or “countryman,” while a landsmanshaft [pl. landsmanshaftn] is Yiddish for the organization or society formed by landsmen of common towns or cities, generally in eastern or central Europe. Yizker bikher [sing. Yizker bukh] are the memorial books, frequently written by a given landsmanshaft to honor and commemorate the historical events and sundry features, characteristics, and personalities associated with its particular city or town. Many of the yizker bikher were written in the years following the Holocaust in Yiddish and Hebrew, although there are also those containing other languages, including: English, French, Polish, Russian, and Spanish. Nowadays, yizker bikher tend to be a treasure trove for genealogists, researchers, and scholars, as they include names of individuals, and very frequently, necrology lists of Jews murdered during the Holocaust. When I was growing up in Chicago back in the 1980s and early 1990s, I was used to hearing about the “Kielcers” and their various gatherings, sometimes taking note of a schedule of events clipped to my grandparent’s refrigerator door. These were the extended surrogate relatives – or landsmen – who hailed from my grandfather’s city of Kielce (pronounced `Kelts’ in Yiddish; `Keltseh’ in Polish), in Central Poland. Like my own grandparents, they were all Holocaust survivors who had immigrated to Chicago in the wake of World War II. They bore an important presence at major family functions, such as my brother’s Bar Mitzvah and my grandfather’s 75th and 90th birthday parties. When my mother was growing up, the Kielcer landsmen were an even more ubiquitous and dynamic presence in her life, since they were all that much younger, a generation earlier, and had just lost their entire world during the Second World War. As a result, most of them were eager to move forward, setting down roots in their adoptive city of Chicago, and giving rise to new and future families. In light of this milieu of transplanted landsmen in which I grew up, I had an inkling from early-on about landsmanshaftn. By extension, I was also exposed at a relatively young age to yizker bikher. Indeed, my grandfather had his own such yizker bukh, written mainly in Hebrew and Yiddish: Al betenu she-harav—Fun der khorever heym [Hebrew and Yiddish for: “About our house which was devastated”] (Tel Aviv: Kielce Societies in Israel and in the Diaspora, 1981), which I recall flipping through from time to time as a somewhat older child. It was then that my grandparents informed me of the existence of other Kielcer landsmanshaftn around the world – in far-off places such as New York, Toronto, and Israel. A few years later, when I worked at the Asher Library, part of the Spertus Institute of Jewish Studies, in Chicago, I once again had regular access to several hundred different yizker bikher. When I moved to New York City over a decade ago to work for the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, I likewise had ready access to literally hundreds of yizker bikher. As of today, I make frequent use of the yizker bikher that are now accessible online through the New York Public Library, as well as those that are accessible onsite at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Studies and the Center for Jewish History in New York City. Since relocating to New York, I have translated excerpts and the entirety of many yizker bikher written both in Yiddish and Hebrew, including the following:

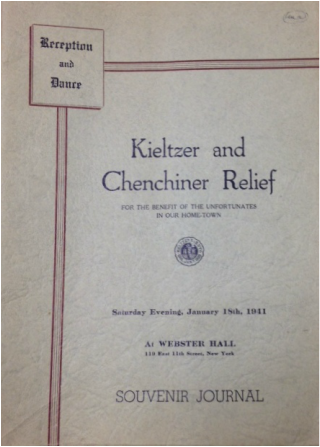

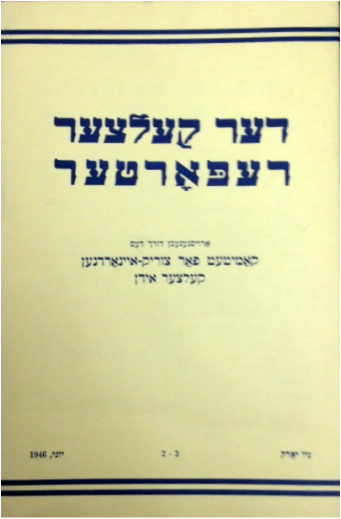

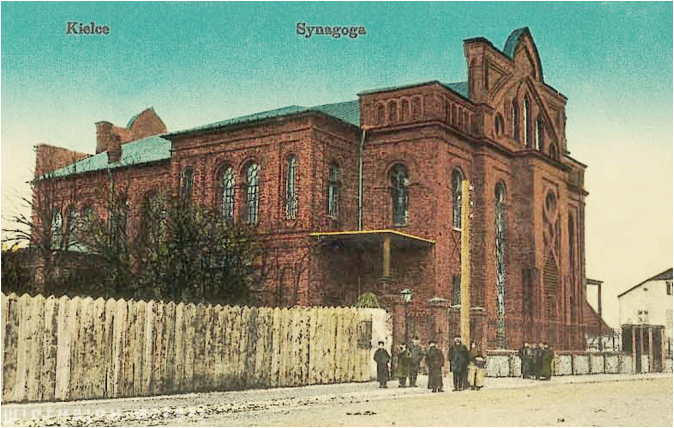

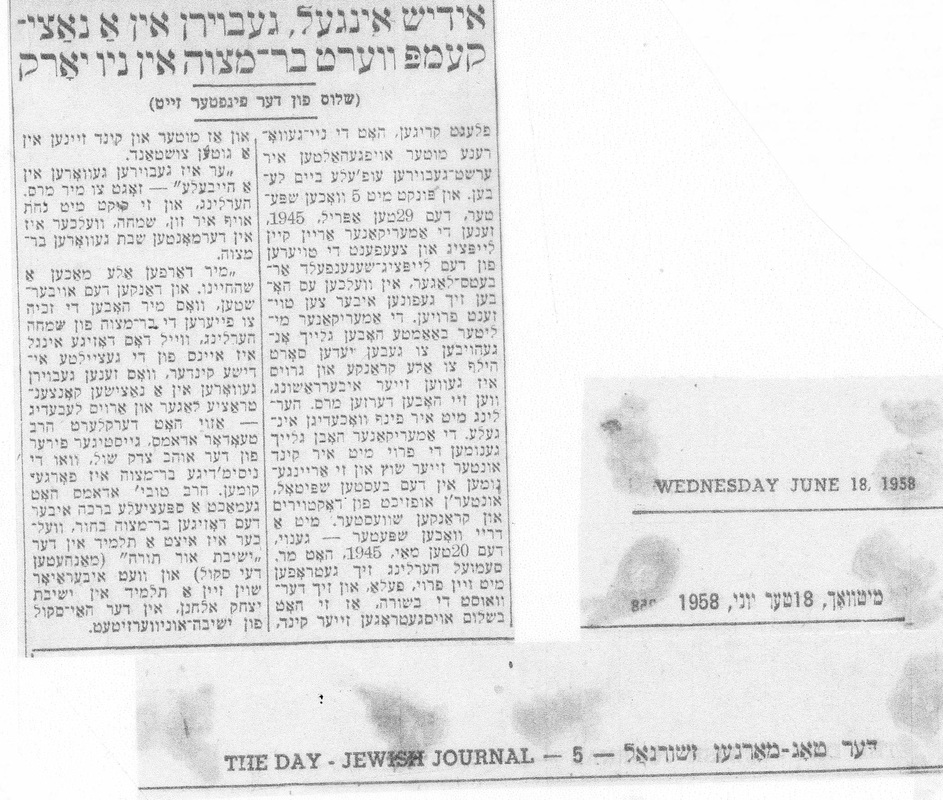

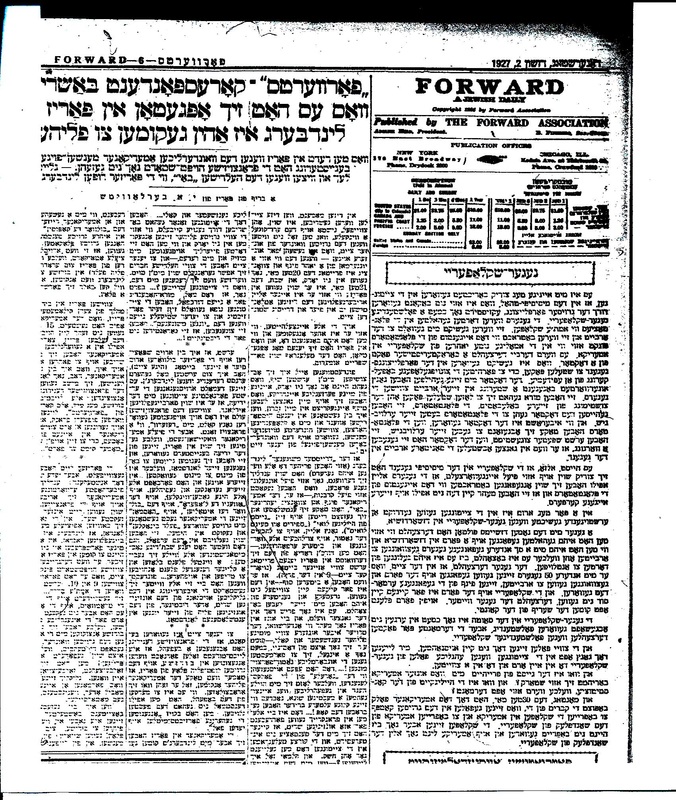

Souvenir Journal of the Kieltzer and Chenchiner Relief (later renamed the “Kieltzer Sick and Benevolent Society of New York”), January 18, 1941. (Courtesy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, NYC, RG 1056, Box 2 (of 2).) Souvenir Journal of the Kieltzer and Chenchiner Relief (later renamed the “Kieltzer Sick and Benevolent Society of New York”), January 18, 1941. (Courtesy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, NYC, RG 1056, Box 2 (of 2).) I have also surveyed and catalogued over 100 different landsmanshaft collections at the YIVO Institute, some of which may be viewed here. Among those landsmanshaft collections at YIVO that personally interested me is that of the “Kieltzer Sick and Benevolent Society of New York” (Record Group 1056), organized in New York on January 7, 1905 as the “Kieltzer Sick and Benevolent Society of Russian Poland, Inc.” The society underwent a few name changes, until finally changing its name officially to the former title in 1954. It is worth noting here that as of 2016, this is one of the few still extant landsmanshaftn in the New York City area – and probably, worldwide – that continues to meet periodically throughout the year for commemorative ceremonies and other functions. The organization, which today often goes by the more informal moniker, “The Kieltzer Society,” has its own website, which may be viewed here, and a related (closed group) Facebook site, accessible at: “Descendants of Jewish Kielce Province.” There is a great deal that may be said of the history of Jewish Kielce – particularly, about the notorious pogrom that took place there at ul. Planty 7/9 on July 4, 1946, during which over 40 Holocaust survivors from Kielce and elsewhere were brutally murdered and maimed by local residents that included police and other officials. Sadly, this is probably the one resonating reason that anybody today has ever even heard of this city. Nonetheless, it is in Kielce that my grandfather lived the first 30-some years of his life, worked as a butcher, married, and raised two sons, before the Holocaust put a roaring end to all of that. I have visited Kielce twice, most recently in the fall of 2014. On both trips there, I made a point of viewing the pogrom site and the remains of the Jewish cemetery. I have also researched and written about various aspects of Jewish life in Kielce, time and time again. One of my publications on the subject may be viewed here. Among the most haunting research finds I made while sifting through the aforementioned archival collection, is that of a Yiddish article, entitled: “A bazukh in Kielce” [“A visit in Kielce”] published in Der Kielcer reporter ["The Kielcer reporter"] in June of 1946, only a matter of weeks or even mere days before the previously mentioned murderous rampage took place (on the 4th of July). The article was written by Sh. Lipshitz, a Yiddish writer for the Vokhenblat newspaper (or “Canadian Jewish Weekly”) who was a native of Kielce’s neighboring city of Radom. He returned to Poland in the wake of World War II to report on the situation concerning Jewish life there. Ironically, although the article patently conveys the vast degree of destruction wreaked on Jewish life in Kielce and in Poland as a whole, at the same time, there are bursts of optimism in Lipshitz’s piece. In reading his account, one might think that there was a brighter future in store for the Holocaust survivors who had converged on Kielce, just right around the bend. Moreover, there is certainly no blatant tone of an ensuing catastrophe lurking in the shadows. Among the key figures whom Lipshitz highlights with regard to Kielce’s postwar Jewish community, or kehile is Dr. Kahane [Lipshitz refers to him as “Dr. Kahaner”], Chairman of the Kielce Regional Jewish Committee, who operated out of the Committee’s building on Planty Street. Incidentally, this was the very same building in which many of the pogrom victims – Dr. Kahane included – would later lose their lives under extremely violent circumstances. At the time of Lipshitz’s visit, Kahane informed him the following regarding the then current state of Jewish life in Kielce: “There are around 300 Jews in Kielce. Some of them work, others trade/bargain, [and still] others receive help from the Committee. The Committee has a good kitchen where hot meals are served for all those who are in need. There is a kibbutz. We must have help … The situation of the Jews is difficult. From such a large Jewish settlement that there once was in Kielce, there remained only 300 Jews, and not all are Kielcers. Some of the 300 are from the surrounding towns…”  Der Kielcer reporter ["The Kielcer reporter"], published by The Committee for the Resettlement of Kielcer Jews, New York, [vol.] 2-3, June, 1946. (Courtesy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, NYC, RG 1056, Box 2 (of 2).) Der Kielcer reporter ["The Kielcer reporter"], published by The Committee for the Resettlement of Kielcer Jews, New York, [vol.] 2-3, June, 1946. (Courtesy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, NYC, RG 1056, Box 2 (of 2).) And yet, even with this less-than-sanguine image, Lipshitz remarks that Dr. Kahane, who was himself incarcerated during the war in a camp in Lemberg [Lwow], [he] “does not speak with any bitterness. But in his eyes burns the fire of hatred for the barbarians, themselves. A German who falls into Dr. Kahane’s hands will not have a Garden of Eden.” However, the following description of the series of events that unfolded on July 4, 1946 makes plainly clear the tragic reality: that there was no way that Dr. Kahane would ever have any such opportunity to demonstrate the hatred that Lipshitz illustrates in his article: “At about 11 o'clock three lieutenants of the Polish Army entered the room in which Kahane was located at that moment. When the officers came into the room, Dr. Kahane held the telephone receiver in his hand. . . They told him they had come to remove weapons. . . One of them walked up to Dr. Kahane, told him to keep calm because soon everything would be over, and then approached him from behind and shot him straight in the head” (Bozena Szaynok, "The Pogrom of Jews in Kielce, July 4, 1946." Yad Vashem Studies 22 (1992), p. 216).  Sh. Lipshitz’s “A bazukh in Kielce” [“A visit in Kielce”], from which some of my translated excerpts in this blog appear. (Courtesy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, NYC, RG 1056, Box 2 (of 2).) Sh. Lipshitz’s “A bazukh in Kielce” [“A visit in Kielce”], from which some of my translated excerpts in this blog appear. (Courtesy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, NYC, RG 1056, Box 2 (of 2).) In the aftermath of the Kielce pogrom, there was, perhaps not surprisingly, a dramatic increase in the number of Jews emigrating from Poland. Many of those émigrés headed westward, while others eventually made their way to what would soon become the Modern State of Israel. The Kielce pogrom was the final test of survival – the proverbial “last straw.” My grandfather was among the “luckier” ones, since he never even returned to Kielce, following his liberation by the American Forces at the end of World War II. Had he returned, I shudder to think whether I would be here today, writing these very words. Bearing this history in mind, I ask, that come the next yortsayt [Yiddish for “anniversary of a death”] of the Kielce pogrom – the 70th – on July 4, 2016, that you please take a few minutes out of your Independence Day celebrations (if you are American, that is) to remember those, like Dr. Kahane, who died tragically on this day, while trying to protect and defend themselves and their fellow landsmen. I also ask you to please consider the immense value that landsmanshaftn and yizker bikher had and continue to have for those who contributed to them, as well as for future generations. Should you have a yizker bukh or any landsmanshaft material that you would like translated, please do not hesitate to contact me at rivka@rivkasyiddish.com.

20 Comments

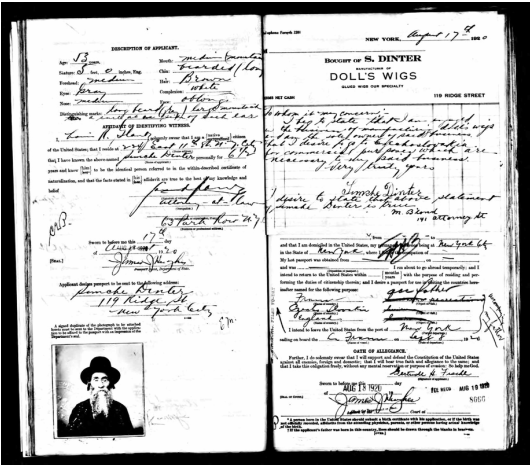

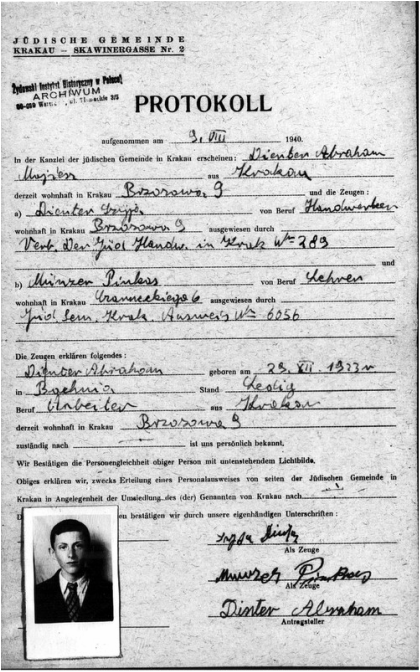

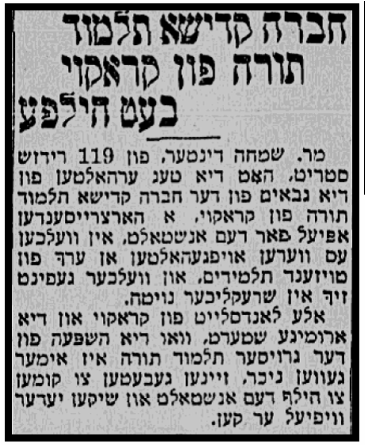

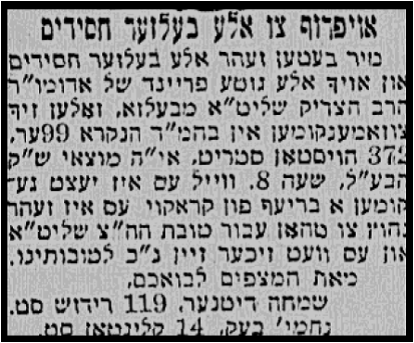

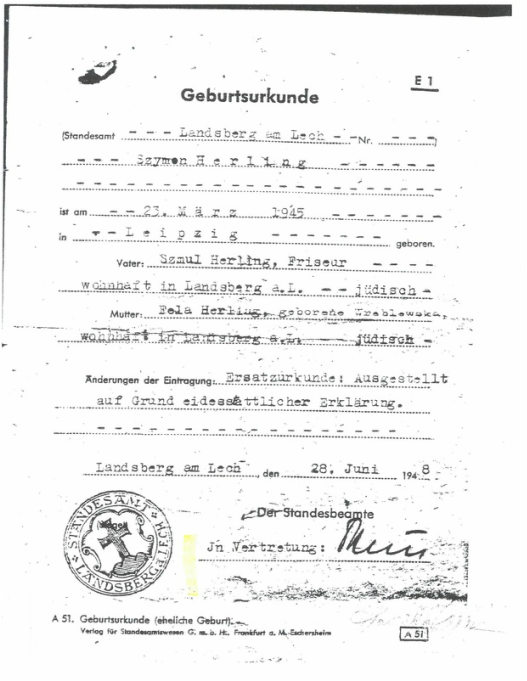

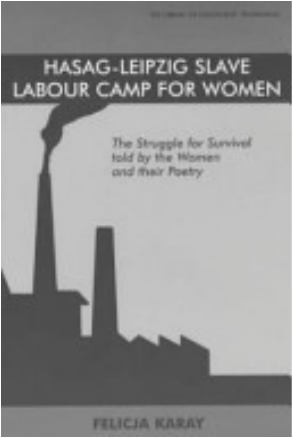

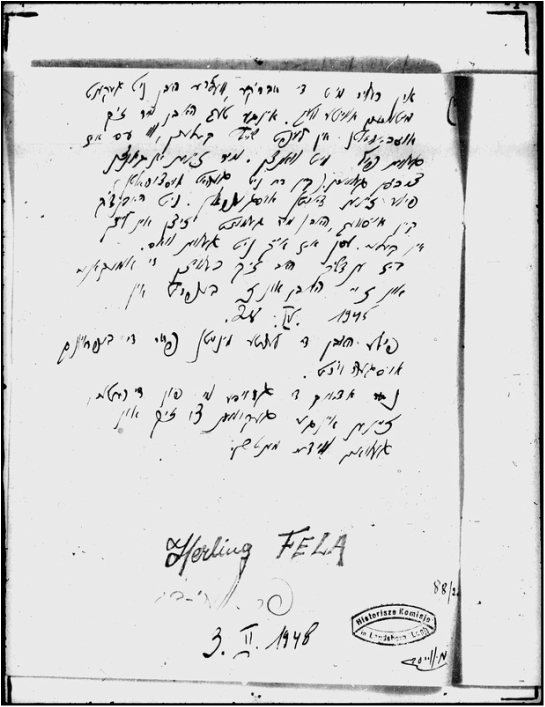

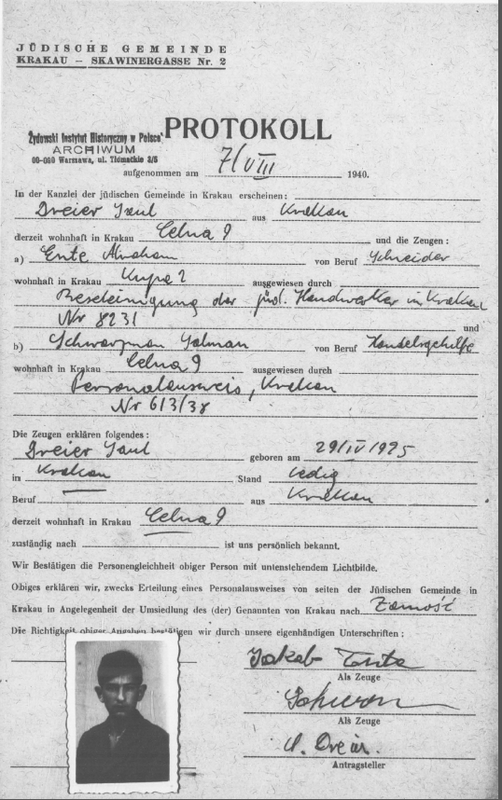

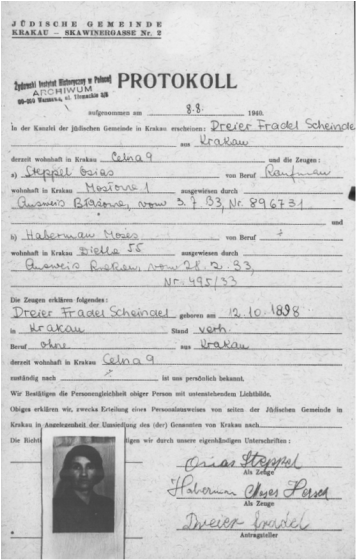

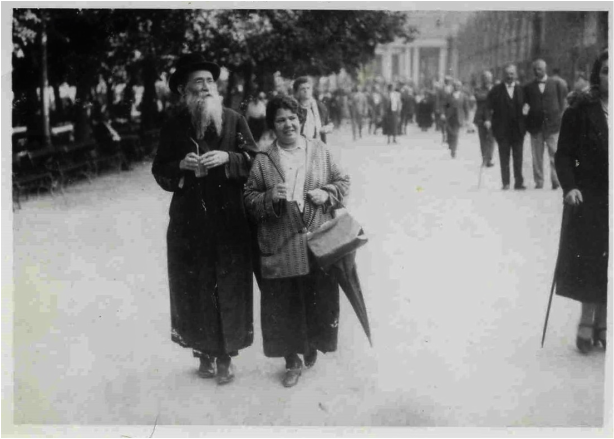

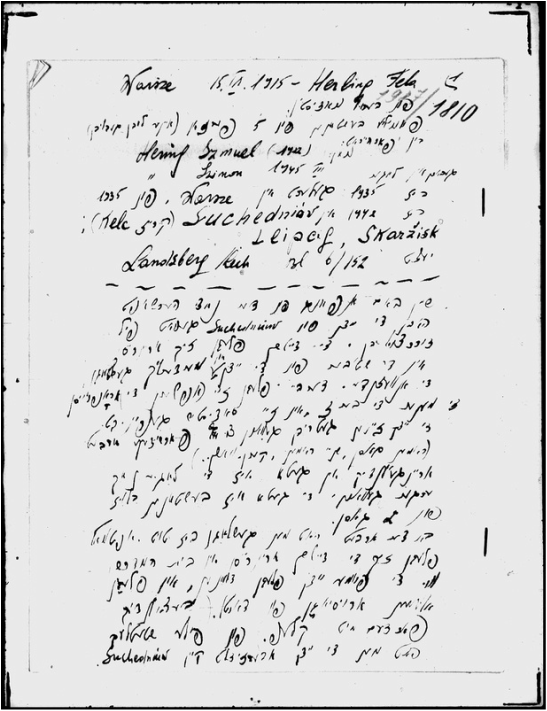

Saul Dreier (on the drums) and Reuwen “Ruby” Sosnowicz (on the accordion) practicing in South Florida. (http://www.thefrisky.com/2015-03-08/two-holocaust-survivors-form-band-in-florida-called-holocaust-survivor-band, accessed 4-21-16). Saul Dreier (on the drums) and Reuwen “Ruby” Sosnowicz (on the accordion) practicing in South Florida. (http://www.thefrisky.com/2015-03-08/two-holocaust-survivors-form-band-in-florida-called-holocaust-survivor-band, accessed 4-21-16). While researching the story about the Dinter family of Brzozowa 9 in Krakow, Poland, featured in my March blog: A Genealogical Journey to 9 Brzozowa Street, Krakow, Poland, I also learned of a surviving family member, a relative of Bina Dreier Dinter. This individual managed to survive World War II, and more recently, has gone on to become a celebrity figure of sorts. The following blog will therefore be a celebration of the life of this man, Saul Dreier, as well as that of his musical partner, Reuwen “Ruby” Sosnowicz. Both men are Holocaust survivors who were liberated around this time of the year, making this an especially apropos point on the calendar at which to relate their story. The close proximity to Passover (or Peysakh, in Yiddish), a holiday celebrating the freedom of Jews from bondage, also played a major role in my decision to write about these two remarkable individuals – who themselves succeeded in escaping a modern-day bondage – 71 years ago. Saul Dreier was born on April 29, 1925 in Krakow, Poland and resided at Celna 9 in an area of Krakow that was quite a distance from Brzozowa 9, where his Dinter family members resided. Saul recalls visiting there on at least one occasion, on a Sabbath day when he was about 11 years old. At the time, the walk seemed to take forever. Saul also remembers climbing the steps inside the building, of which there were – and still are – quite a few. His family, like that of the Dinters, were Belzer Hasidim. What’s more, his grandfather, Berl Dreier – a very religious man – was a cantor in a local Krakow synagogue. Saul’s grandfather, along with other family members, is depicted in the only family photograph that Saul possesses to this day from the prewar era, thanks to an uncle who was already residing in Brooklyn prior to the outbreak of World War II, and gave him the photograph.  Members of Saul Dreier’s immediate family prior to World War II. Included here is Berl Dreier, the cantor grandfather mentioned in this article (seated, with a beard), as well as Saul’s mother, Fradel Scheindel Dreier (standing, far right). Aside from Saul’s grandfather, who died a natural death, all of the other individuals depicted here were murdered in the Holocaust. (Thanks to Saul Dreier for sending me this photograph and for allowing me the use of it here.) Members of Saul Dreier’s immediate family prior to World War II. Included here is Berl Dreier, the cantor grandfather mentioned in this article (seated, with a beard), as well as Saul’s mother, Fradel Scheindel Dreier (standing, far right). Aside from Saul’s grandfather, who died a natural death, all of the other individuals depicted here were murdered in the Holocaust. (Thanks to Saul Dreier for sending me this photograph and for allowing me the use of it here.) As for Saul’s upbringing, he attended Heder, the religious school attended by boys of a certain age, as well as public school. Although Saul was familiar with Yiddish before World War II, he was already of the generation of young Polish Jews who spoke predominantly Polish. As he told me in my recent telephone conversation with him, it was actually during the war when he learned a great deal more Yiddish, as this was the main language of communication for most incarcerated Polish Jews. According to Saul, even Jews who could speak Polish no longer wished to do so, as they felt much hostility and antipathy toward the Poles, whom they felt had betrayed them to the Germans. When World War II broke out on Sept. 1, 1939, Saul was only 14 years old; according to him, still very much a child. He did not know exactly what was happening around him at the time, but by early March 1941, “the Germans ordered the establishment of a ghetto, to be situated in Podgorze, located in the south of Krakow, rather than in Kazimierz, the traditional Jewish quarter of the city” and the neighborhood in which the Dinter family resided. (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, accessed 4-12-16). Like thousands of other Jews, Saul and his family found themselves imprisoned in the Krakow ghetto. Ultimately, he was forcibly sent to the nearby Plaszow Concentration Camp, immortalized in Schindler’s List, Steven Spielberg’s award winning film of 1993. Indeed, the filming for this film was actually conducted on location, close to where the former grounds of Plaszow once stood. In the Plaszow Concentration Camp, established in March 1943, Saul was forced to build barracks for incoming Jewish prisoners from all over Poland. In the meantime, a deal was made between German factory-owner and Nazi Party member, Oskar Schindler and Amnon GÖth, the S. S. commandant of the Plaszow Concentration Camp. This agreement permitted Schindler to build a sub-camp in which to house Jews working for his enamel factory, as well as for 2 other factories. According to Saul, this affected approximately 1,000 slave laborers. Saul was assigned to one of these other 2 factories, the N. K. F. (Neue Kühler -und Flugzeugteilefabrik) factory, where he was forced to repair airplane radiators. The entire area in which Saul and these other prisoners labored was carefully guarded by the German S. S. and uniformed Ukrainian volunteers. Much of this story is featured in the aforementioned film, and also discussed in the recently published international bestseller by Jennifer Teege: My Grandfather Would Have Shot Me: A Black Woman Discovers Her Family’s Nazi Past. From his factory, Saul and numerous other slave laborers were forcibly marched, under guard, to Plaszow. From there, they were loaded onto cattle cars headed for Auschwitz. However, upon arrival in Auschwitz, the Germans shipped Saul westward to the Mauthausen Concentration Camp, in Austria. Initially, he was incarcerated at Mauthausen. Later on, though, he was sent to a sub-camp in Linz, Austria, approximately 20 kilometers from the concentration camp, where he was again forced to do slave labor in a factory. Saul remained in Linz until the end of the war, at which point he was liberated in early May of 1945 by the 11th Armored Division of the U. S. Army.  Saul Dreier shortly after liberation and following surgery on his hands, early May of 1945. (Thanks to Saul Dreier for sending me this photograph and for allowing me the use of it here.) Saul Dreier shortly after liberation and following surgery on his hands, early May of 1945. (Thanks to Saul Dreier for sending me this photograph and for allowing me the use of it here.) Saul related to me that shortly after liberation, he was aided by an American soldier – a Jewish medic from Manhattan with whom Saul conversed in Yiddish – as it was the common language for both men. At the time, Saul had gangrene in his hands, which he incurred when he and other prisoners were struck by a bomb. The U. S. officer whisked him off on his jeep to the nearest hospital, where he received immediate medical treatment and was operated on right away. A photo was taken of Saul only a day or so after this operation, which may be viewed here. Sometime thereafter, Saul was taken overnight by the Jewish Brigade southward into Italy. He ended up in a D. P. (Displaced Persons) camp in Santa Maria di Bagni (today, Santa Maria al Bagno), located at the heel of the country, where he remained for 5 years. It was there that Saul learned to speak Italian and to play the drums. The music lessons would prove especially useful to him years later, when he would decide to establish his musical band. But more about that in a moment. Saul was the sole survivor of his immediate family. However, in 2010, after 65 years of searching, the Red Cross helped reunite him with his cousin, Lucy Weinberg, who was a survivor of Schindler’s group of factory workers, and who had subsequently settled in Montreal. Their amazing story is featured here. Ultimately, Saul settled in the United States, where he met and married his wife, Clara, also a Holocaust survivor, in 1957. The two went on to have 4 children and 6 grandchildren together. Sadly, Clara passed away on February 16, 2016. For many years, Saul lived in Elizabeth, New Jersey, where he worked in the real-estate sector, and retired close to 20 years ago. He now resides in South Florida. In the spring of 2014, Saul was inspired to start a musical band, which he named the “Holocaust Survivor Band,” feeling that this would help bring greater meaning and enjoyment to his later years. His major source of inspiration was an article he read about “the death of Alice Herz-Sommer, a 110-year-old survivor and accomplished pianist who’d survived a concentration camp by playing music.” Through word of mouth, Saul met another musically talented Holocaust survivor named Reuwen “Ruby” Sosnowicz, who played the keyboard, the accordion, and various other instruments. At the time, Saul was 89 and Ruby was 85. Saul convinced the former hairdresser, photographer, and professional musician to join him in his new venture, and the two have been performing together ever since. Ruby Sosnowicz is a native of Warsaw, Poland, born into a large and musical family. During World War II, he was incarcerated with his family in the Warsaw ghetto, from which he managed to flee. He escaped death by hiding in the barn of a sympathetic Polish farmer, who would bring him food whenever he went out to feed the horses. (Huffington Post, accessed 4-12-16). Like Saul, Ruby was married to his wife, Regina, for over 50 years. Ironically, she passed away very recently, within days of Saul’s wife. Both women, unfortunately, were ill for a number of years. Along with the accompaniment of band members, Chanarose Sosnowicz – Ruby’s daughter – Jeff Black, a British-born rhythm guitar player, and Mark Horowitz, a saxophone player, the two men feature a wide array of music, including Yiddish Klezmer, Hasidic Nigunim, Tango, Rumba, and Hebrew, Polish, and Russian songs, among others. According to Saul, he and Ruby can “play everything” – whatever the listeners want to hear. Two years after the initiation of their band, Saul and Ruby have been featured in the articles of several publications and on various media sites, including: the Huffington Post, JP Newsroom, the New York Times, Tablet Magazine, CBC Radio, and YouTube. They have already played at many points on the map of North America, including: Brooklyn, Cleveland, Detroit, Hamilton, Ontario, Las Vegas, Reading, Pennsylvania, and South Miami. On occasion, they have even been accompanied at some of these venues by the likes of world-renowned Yiddish singers, such as Dudu Fisher and Lipa Schmeltzer. Presently, Saul and Ruby have their hearts set on performing overseas in Poland and Israel, where they have been invited to perform, as well as in Germany. Their dream is to return to the country of their childhood and to perform outside of the Auschwitz Concentration Camp, where so many of their loved ones perished. This is an opportunity to help these two Holocaust survivors realize a dream and do a great mitzvah [or mitsve; a good deed] – to play their music, celebrating their survival, at the gates of Auschwitz. Even the smallest contribution would be valued and make a difference. Saul and Ruby need $8,000 to make their dream come true. Right now, they only have $500. Anyone who would like to be part of this mitzvah can visit: https://www.gofundme.com/yphjjxdg.  Front doors of the Dinter family residence at Brzozowa 9, Krakow, Poland. (Photograph taken by Rivka Schiller, September 2014.) Front doors of the Dinter family residence at Brzozowa 9, Krakow, Poland. (Photograph taken by Rivka Schiller, September 2014.) Two years ago I met several descendants of Rabbi Simcha Dinter (1867-1929), an active member of the Belzer Hasidic dynasty and a right-hand man to the then third and fourth Belzer Rebbes, respectively, Rabbis Yissachar Dov Rokeach (1851-1926) and his son, Aharon Rokeach (1880-1957). When the family learned that I was traveling to Poland last fall, they asked me if I would take photographs of the Dinter family property in Krakow, located at 9 Brzozowa Street in the once heavily Jewish neighborhood of Kazimierz. When I reached 9 Brzozowa Street, I expected to find a small house. However, much to my pleasant surprise, I found myself gazing up at an impressive stone building, several stories high. Fortunately, one of the tenants of this apartment building was leaving and allowed me to enter and take photographs of the building’s interior. Unlike what I witnessed in Warsaw, my grandmother’s city of origin, in which the vast majority of buildings did not survive the bombings of World War II, this building is quite intact. Moreover, it has been extremely well maintained. It still bears the original, huge, and intricately hand-carved wooden front doors. From the interior staircase landing, I peeked out the window overlooking the sizable backyard, where, according to Dinter family members, two wooden frame houses formerly stood. I began to picture the celebration of the Jewish holiday of Sukkot, the large, extended Dinter family, along with the building’s other Jewish tenants seated in the Sukkah, eating their meals, and singing festive holiday songs.  View of the Dinter family’s expansive former backyard from the building’s interior. (Photograph taken by Rivka Schiller, September 2014.) View of the Dinter family’s expansive former backyard from the building’s interior. (Photograph taken by Rivka Schiller, September 2014.) After I returned to New York, the Dinter family asked me to assist them with additional genealogical research about their family, particularly about their progenitor, Rabbi Simcha. Following is the story of the Dinter family and the biography of Rabbi Simcha, as it was related to me by one of his grandsons. Rabbi Simcha was one of the Gabbais (or Gabbaim; trusted aides) to the aforementioned Belzer Rebbes. Upon his marriage to Bina Dreier, Rabbi Simcha moved from the town of Belz to the city of Krakow, the hometown of his new bride and the Dreier family’s site of residence.  View of Brzozowa 9, Krakow, Poland, from a distance. (Photograph taken by Rivka Schiller, September 2014.) View of Brzozowa 9, Krakow, Poland, from a distance. (Photograph taken by Rivka Schiller, September 2014.) In Krakow, Rabbi Simcha purchased a large apartment building in the historically centrally-located neighborhood of Kazimierz, the city’s predominantly Jewish quarter. The Dinters had eight children and owned a family business that made medical uniforms. Rabbi Simcha was a major financial supporter of the Belzer Hasidim. Not only did he give generous donations from his own funds, but he also raised money both in Galicia and in America. Beginning in 1908, Rabbi Simcha made more than a dozen trips between Krakow and America, speaking to Belzer Hasidim about the importance of sending money to the Belzer community in Europe. On his 1914 visit to America, Rabbi Simcha arrived with his wife and five of his children. When shortly thereafter, World War I broke out, the family spent the remainder of the war and beyond on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Rabbi Simcha started a business producing wigs for dolls. In those day, dolls were made of porcelain and wigs were glued-on. Before the war, most of the toys and dolls sold in America were manufactured in Germany, and the war curtailed this production. As this created a newly-found opportunity, some Jews from Galicia (then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire) went into this business.  Simcha Dinter’s American passport application (including a photograph of the applicant), c. 1920. (Thanks to Gideon Goldstein for providing this image.) Simcha Dinter’s American passport application (including a photograph of the applicant), c. 1920. (Thanks to Gideon Goldstein for providing this image.) When the war ended in late 1918, the Belzer community was in dire need of financial assistance. Rabbi Simcha expended his time and energy in raising money for the Belzer community in Europe. Rabbi Simcha's letters-to-the-editor were published in Yiddish newspapers and advertised that he would be speaking on the Lower East Side as part of this fundraising campaign. In 1920, Rabbi Simcha, who had become an American citizen, applied for a U. S. passport to return to Europe. Interestingly, his passport photo showed him appearing as a typical Hasidic Rabbi. Perhaps today it is not unusual to see somebody who looked like Rabbi Simcha on the streets of New York City, but in 1920, it was quite unusual. The first thing almost all religious male Jews did upon arrival in America was to shave or trim their beards, cut off their sidelocks (Peyes), get rid of their black hat, and to dress like average American males of that day. But such was not the case with Rabbi Simcha. His passport application describes him as having a “long beard (grey), large moustach[e], [and] a curl at [the] side of each ear.” In his passport photo, Rabbi Simcha is wearing his rabbinical black hat – clearly, he refused to remove it for this photo.  Simcha Dinter posing in traditional Hasidic garb for his American passport application, c. 1920. (Thanks to Dinter family members for providing this photograph.) Simcha Dinter posing in traditional Hasidic garb for his American passport application, c. 1920. (Thanks to Dinter family members for providing this photograph.) In 1923, Rabbi Simcha can be found in a photograph with the Belzer Rebbe and his aides, which was taken in Marienbad, Czechoslovakia (today, the Czech Republic), a well-known resort where many Hasidim vacationed prior to World War II. During this visit to Marienbad, Rabbi Simcha and his wife Bina were photographed strolling in the town square. Rabbi Simcha's four daughters and one son remained in New York, while he and his wife returned to Krakow. Afterward, Rabbi Simcha made yearly trips to New York, raising funds for the Belzer community. Rabbi Simcha died in 1929; his wife Bina, in 1936. They are both buried in the new Jewish cemetery in Krakow on Miodowa Street. Sadly, the Dinter family met the same fate as most of Poland’s Jews. The three children of Rabbi Simcha who still resided in Poland, not being American citizens, found themselves trapped there when World War II broke out on September 1, 1939. In the summer of 1940, the Germans ordered the majority of Krakow’s Jews to relocate to other ghettos. The Dinter family chose to go to the Bochnia ghetto, where some relatives owned property. Along with their children and spouses, Rabbi Simcha’s three children managed to survive until the first Aktion [i.e., the assembly and deportation of Jews to concentration or death camps] of the Bochnia ghetto in the summer of 1942. Most of the Dinter family perished during this Aktion, others during the Aktion in the summer of 1943. During these Aktions [Yiddish: Aktsyes], those who were not killed in Bochnia were deported to death camps, where the overwhelming majority were murdered upon arrival. At the war’s end, of the entire Dinter family that had been caught up in Hitler’s murderous web, only one of Rabbi Simcha’s grandsons had managed to survive. Fortunately, research discovered a rare, well-preserved document issued by the Krakow Jewish community on August 9, 1940, just prior to the Dinter family’s relocation to the Bochnia ghetto. This document, which bears a distinct photo, is the registration form of Abraham Dinter, a teenage grandson of Rabbi Simcha. Tragically, Abraham Dinter would be murdered only two years later, in August of 1942, in the Belzec death camp.  Abraham Dinter (b. December 29, 1923 - d. 1942), one of the many Dinter family members who perished in the Holocaust. Note the address of residence indicated on this form, issued by the Jewish community of Krakow and dated August 9, 1940: Brzozowa 9, Krakau (Krakow). (Thanks to the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw, Poland for uncovering this document, and to the Dinter family, for allowing me the use of it here.) Recently, an article was published in an Ultra-Orthodox journal printed in Israel, detailing the relationship between Rabbi Simcha and the Belzer Rebbe. Dinter family members asked me to translate this article. The article, which was written in Hebrew, contained undated newspaper clippings pertaining to Rabbi Simcha and his fundraising on behalf of the Belzer Hasidim. The Belzer Rebbe is often referred to as the “Tzaddik” [i.e., a frequently used title for a Hasidic leader or rabbi]. I was glad to assist the family with this translation as well as to visit their former homestead at 9 Brzozowa Street in Krakow. In some sense, this is both where the saga surrounding the Dinter family begins as well as ends. At this late date (2016), there are no known Dinter family members residing in Krakow or in Poland, for that matter. The family’s scattered remnants now reside in Israel, the United States, and in Canada, where they have sowed new roots and sprouted new branches. Following are some of the aforementioned newspaper clippings, originally in Yiddish and Hebrew, along with my accompanying translations:  Der Tog-Morgen Zshurnal/The Day-Jewish Journal [?] Chevra Kadisha Talmud Torah of Krakow Requests Help [Author not indicated, undated; Yiddish] Mr. Simcha Dinter of 119 Ridge Street [i.e., the Lower East Side, Manhattan, New York] received a heart-wrenching appeal from the Gabbais of the Chevra Kadisha Talmud Torah of Krakow, for the institute, which maintains approximately one thousand students, and which finds itself in terrible need. All the kinsmen from Krakow and the surrounding towns in which the influence of the great Talmud Torah was always well-recognized, are asked to come help the institute, and everyone should send as much [money] as he can.  Der Tog-Morgen Zshurnal/The Day-Jewish Journal [?] Announcement to All the Belzer Hasidim [Author not indicated, undated; Yiddish] We greatly implore all the Belzer Hasidim, as well as all the good friends of Our Master, Our Teacher, and Our Rabbi – may he live for many good days, amen – from Belz, that they gather together at the religious study house known as the “99er,” 372 Houston Street [i.e., the Lower East Side of Manhattan], if God wills it, this coming Saturday night at 8 o’clock. For a letter just arrived from Krakow; it is very urgent to do good on behalf of the Rabbi, the Tzaddik – may he live for many good days, amen – and it will certainly be for our own good, as well. From those who are anticipating your arrival, Simcha Dinter, 119 Ridge Street Nechemia Beck, 14 Clinton Street [i.e., the Lower East Side of Manhattan].  Birth certificate of Simon [Szymon] Herling, born to Szmul and Fela Herling in Leipzig, Germany, on 23 March 1945. Issued on 28 June 1948 in Landsberg am Lech, Germany, where the Herling family resided in a D. P. camp following World War II. No specific mention is made here to the fact that Simon Herling was born in a German concentration camp. (Thanks to Simon Herling for providing me with this scan of his birth certificate.)  The book by Felicja Karay that makes explicit reference to Fela Herling and the other women who gave birth to infants in the Leipzig-Schönefeld concentration camp (http://goo.gl/pUv2bG). The book by Felicja Karay that makes explicit reference to Fela Herling and the other women who gave birth to infants in the Leipzig-Schönefeld concentration camp (http://goo.gl/pUv2bG). When I first made the acquaintance of Simon Herling, the individual who was born in a concentration camp, whom I wrote about a few months ago in my November blog, "Miracle Birth in a Concentration Camp," I never would have imagined what a positive domino effect that would have on Simon, me, or on other people, for that matter. Ever since I read his Yiddish article from 1958 relating the circumstances of his birth and making reference to other surviving infants born in the Leipzig-Schönefeld concentration camp (a sub-camp of the better known, Buchenwald concentration camp), I have been on a mission to find out who those other infants were and what their ultimate fate was. The odds of children being born in Nazi concentration camps and surviving World War II were so slim, that I was significantly moved by this account. So much so, that I wanted to employ my research-detective skills to follow through on this story, wherever it would ultimately lead. Here is how this positive domino effect series of events has unfolded, thus far: A few days after I posted my blog about Simon, I was contacted by a representative of the British online newspaper, The Independent, who asked me if I would allow the newspaper to reprint my article, “Miracle Birth in a Concentration Camp.” Dina Rickman, one of the newspaper’s employees, is a former client of mine and receives my blogs. When she saw my piece, she thought it might be of interest to her newspaper. The timing of things also worked out well, as Kristallnacht (literally, “Crystal Night” or loosely, “Night of Broken Glass”) fell out right around that time, in early November. With Simon’s approval, I agreed to have the article reprinted. A few days after my article was reprinted in The Independent under the following title: "How a Jewish Woman Survived Pregnancy in a Nazi Concentration Camp to Give Birth to Her Son," I received a most unexpected long-distance phone call from Germany – the Buchenwald Memorial Site – of all places. The young woman who phoned me identified herself as Mackenzie Lake, an American doing ecumenical volunteer work at Buchenwald for the year. She was calling in regard to my article, she said, as the Buchenwald Memorial Site was eager to get in touch with Mr. Herling. They wanted to invite him to the Holocaust survivor gathering their museum would be having in April 2016. Since I now had this unforeseen connection to Buchenwald, I told Mackenzie that I was on a mission to find out what had happened to the other infants who had apparently been born in the same concentration camp as Simon and survived the war. Mackenzie informed me that she would see what she and her colleagues could find in their files onsite; and at that point, we left off that we would be in touch. After I got off the phone with Mackenzie, I immediately followed up with Simon, gave him Mackenzie’s contact information, and let it go at that. I was quite hopeful that Simon would find the wherewithal to attend this event – especially, seeing as he would be one of – if not the very youngest survivor – in attendance there. As I learned more recently from Simon, who in turn spoke with Mackenzie, at the present time the Buchenwald Memorial Site foresees having roughly 40 Holocaust survivors who were incarcerated within the Buchenwald concentration camp network in attendance, this coming April. Furthermore, in one of my most recent telephone conversations with Simon, he informed me that he does indeed plan to attend the gathering at Buchenwald, in the company of his daughter, and visit the site of the concentration camp in which he was born. A few weeks after all of these exchanges, I received an email and book scan from Mackenzie stating that after some serious digging, she and her curator and archivist colleagues, Dr. Harry Stein and Sabine Stein, had located some relevant-sounding information about the women who had given birth in the Leipzig-Schönefeld concentration camp at the tail end of World War II. Felicja Karay, in her scholarly work, Hasag-Leipzig Slave Labour Camp for Women (Vallentine Mitchell, 2002), states the following (page 163): Some women who had been brought to the camp in the early stages of pregnancy had disregarded orders and not registered. Hanka Kurtz worked in the plant throughout her entire pregnancy, and was lucky enough to receive a great deal of help from her German manager. Fela Herling was able to hide her pregnancy for eight months, but since she appeared to be plump and healthy, she was assigned the harder tasks. Until one morning a woman in her block went into labor. As a result, it was announced at roll-call that if all the pregnant women did not report, the entire block would suffer collective punishment and the offender would be hanged. Herling reported, and three weeks later gave birth to a son in the Revier. She was placed on a transport list, but the train could not be sent out because the Front was now too close, and thus she was saved. The night before the camp was evacuated, Hanka Kurtz gave birth to a daughter, and both mother and child survived. The fate of the other woman Mirka (last name unknown), who gave birth is not known. At around the same time Róźka Millstein also had a child and remained in the camp after the evacuation thanks to a bribe the Polish prisoners gave to the SS overseer. What came to light from the above passage that Mackenzie emailed me were both actual names of women who had given birth in the Leipzig-Schönefeld concentration camp – something that had been entirely unknown beforehand – as well as an important reference to Fela Herling, Simon’s mother. Important, because the reference provided a footnote indicating that Fela had provided a testimony about her wartime experiences to Yad Vashem, the leading Holocaust memorial site in Israel. I forwarded all of this information to Simon, and just as I had suspected, he had had no knowledge of his mother’s testimony until now. I informed Simon that I would do my best to track down a copy of his mother’s testimony, hopefully, within the United States. The following day I phoned the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D. C. and spoke to an extremely helpful reference librarian there named Ron Coleman. When I provided Ron with the citation to the testimony as it appeared in Karay’s book, he was immediately familiar with the format and was able to confirm that the museum does indeed have a digitized duplicate of the text, which he subsequently emailed me as we were still chatting. My hunches about the testimony were correct: it was taken down by hand in Yiddish in the Landsberg D. P. camp where Simon and his parents resided following World War II, in 1948. Right away, I forwarded the testimony to Simon, and before long, he had asked me to translate this text for him. Interestingly, this testimony was given by Fela Herling a decade prior to the interview she later gave Asher Penn for his article in the Yiddish language newspaper, Der Tog-Morgen Zshurnal/The Day-Jewish Journal, which I translated for Simon and wrote about here a few months ago. I knew that one of the gnawing questions Simon had always had was the fate of his older sister, who had sadly perished in the Holocaust at a tender age. As it turns out, the testimony did provide some insight into his sister’s fate, although her actual name is not mentioned in the text. Perhaps it was simply too painful and raw at the time for Fela Herling to explicitly mention her murdered daughter’s name. According to Fela’s statement, shortly before the Aussiedlung – or forced resettlement under the Third Reich – of Suchedniów, the town in which she, her husband, and child resided prior to the outbreak of the war, it became so terrible, that those who were to go do [forced] labor in a munitions factory in Skarżysko HASAG [were told] that the ones who reported [for forced labor] would survive. (8 kilometers from the town). Young people were able to report, people, families without children. I, my husband, and child planted ourselves beside the vehicle, so as to be taken to do [forced] labor. The Germans only selected young people. The Obersturmführer stood by, observing how people were being sorted. When he saw me, my husband, and child, he threw the child to the side, and pushed us into the vehicle. I attempted to jump from the vehicle and remain with my child, but the Sturmführer beat me up with a slap and pushed me back in. That is how I became separated from my child. Two weeks following that, the Aussiedlung took place (on Yom Kippur), in the town of Suchedniów. Everyone was deported to Treblinka.  The first and last pages of the six-page Yiddish testimony of Fela Herling recorded on February 3, 1948 in the Landsberg D. P. camp in Germany. (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Record Group 68.095M, “Testimonies (M.1.E)”; YVA M.1.E/1810). (Thanks to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D. C., Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, Israel, and to Simon Herling, for permitting me the use of this text.) For the first time in all these years, Simon finally had a clearer sense of what had befallen his sister, who was likely either murdered in Suchedniów, or deported to Treblinka with the majority of the town’s Jews.

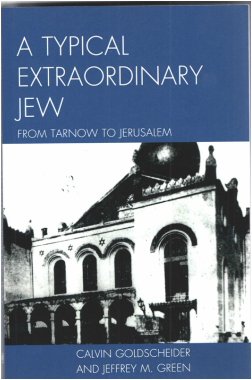

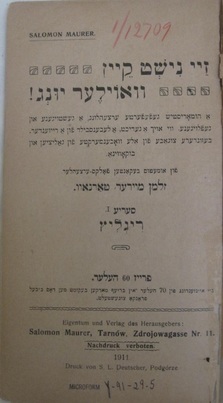

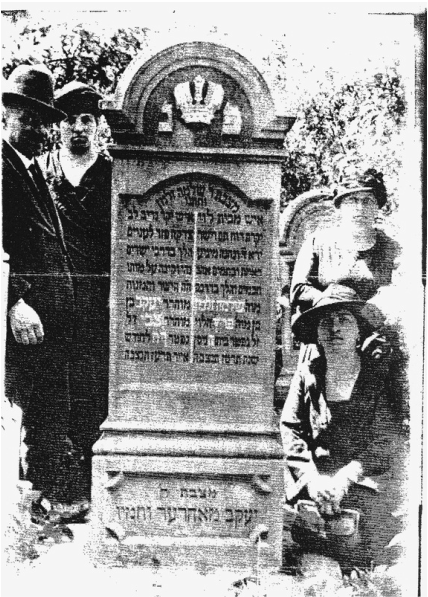

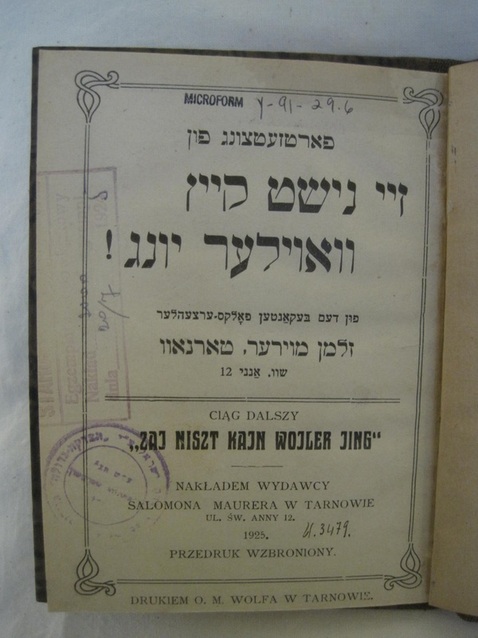

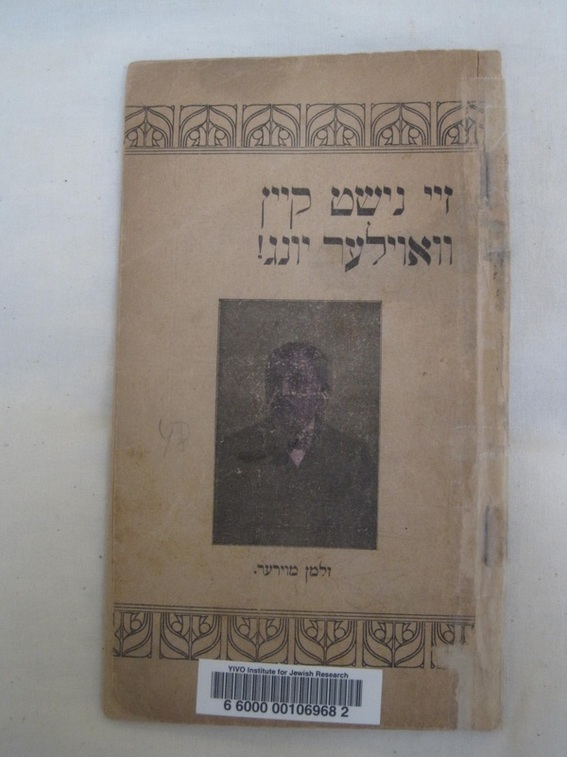

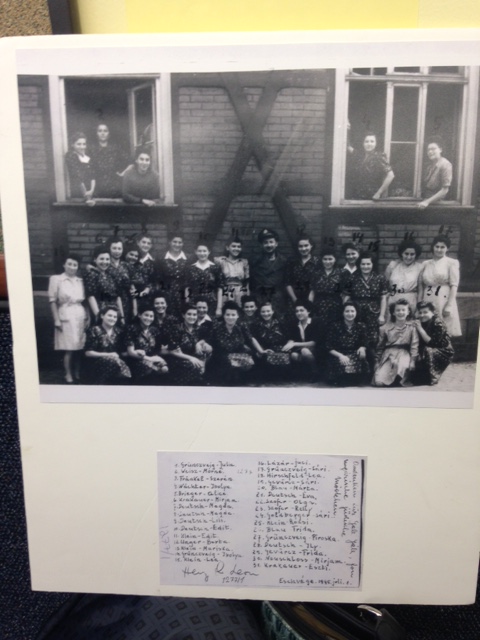

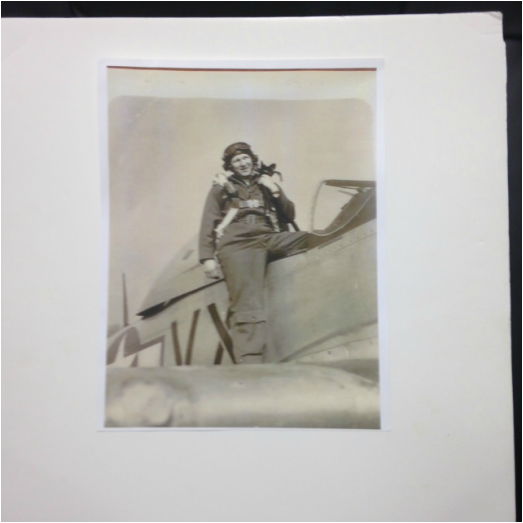

Prior to my translating Fela Herling’s testimony, I was in touch with yet another department of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Holocaust Survivors and Victims Resource Center, where I consulted William Connelly about the fate of the other children born in the Leipzig-Schönefeld concentration camp. He advised me to submit forms with the names of the individuals I was seeking – names that I had subsequently learned from the book excerpt that Mackenzie Lake had sent me and cross indexed in Buchenwald’s prisoner files. And indeed, that is precisely what I did. So now, it is a matter of waiting, networking, and remaining optimistic that with all of our joint international and transnational research efforts, we will ultimately learn the fate and identities of the other surviving children who were born alongside Simon Herling at the close of World War II. I hope that at some point in the not-too-distant future I will have more concrete information about all of this to share with my readers. But in the meantime, if anyone has any knowledge of these yet unaccounted for children, or any ideas or suggestions about how to locate these individuals, please do not hesitate to get in touch with me at rivka@rivkasyiddish.com.  The cover page of the book that ultimately led to Russ Maurer’s discovery of his relative, Salomon Maurer’s book publication. Depicted here is the Great Synagogue of Tarnow. (Thanks to Russ Maurer for providing this additional information.) The cover page of the book that ultimately led to Russ Maurer’s discovery of his relative, Salomon Maurer’s book publication. Depicted here is the Great Synagogue of Tarnow. (Thanks to Russ Maurer for providing this additional information.) Several months ago Russ Maurer contacted me, inquiring whether I would be interested in translating a Yiddish monograph of humorous stories and poems that is roughly 80 pages and was printed in Tarnow, Poland, in 1925. The author, Salomon Maurer (1873-1942), had been a second cousin of Russ’ grandfather. According to Russ, “Salomon had the reputation within the family as a funny guy.” However, until very recently, Russ had not been aware that Salomon had actually published some of his original stories. As it turned out, Salomon had, in fact, published his stories in Yiddish in the book, “Zay nisht keyn voyler yung” (“Don’t Be a Good Young Man”), which Russ was now asking me to render into English. In Russ’ words, “Salomon perished in the Holocaust, so translating this work is a way to bring him to life.” The manner in which Russ had learned of his relative’s book is in itself a compelling and inspiring – albeit, round about story. Given his genealogical proclivities and roots in the Tarnow region, Russ belongs to a Facebook group of people interested in Jewish Tarnow. Following up on a group member’s suggestion, Russ began to read a book entitled, “A Typical, Extraordinary Jew: from Tarnow to Jerusalem” (Hamilton, 2011) by Calvin Goldscheider and Jeffrey M. Green. The book is based on the recollections of Shmuel Braw (1906-1992), a Holocaust survivor who hailed from Tarnow and had a keen memory for the various personalities in his pre-World War II Galician Jewish community. Among the professions he recalled was that of the “frachters of Tarnow, messengers, men who took letters and packages from Tarnow to Krakow, sometimes money to be deposited in a bank or paid to a creditor” (Goldscheider and Green, p. 33). According to Shmuel, one of these “frachters,” a said Zalman Maurer, wrote a book, “Sei Nisht Zee Gut Yingle (Don’t be too good, lad)” (p. 33). Granted, Shmuel’s recollection of the book’s title was slightly “off.” But considering that he had most likely not seen a copy of this volume for several decades, he was actually not so far off the mark. When Russ read this reference to Zalman Maurer, he found the book’s correct title in WorldCat, an international library database. This led him to the National Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Massachusetts. Catherine Madsen, the Yiddish Book Center’s bibliographer, located a citation for the book in the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research’s online catalogue. YIVO’s catalogue characterized the work as that of Yiddish wit and humor, a point of special interest to Russ, since this sounded entirely consistent with the family lore surrounding Salomon. In addition, according to genealogical notes made by Russ’ own father, 25 years earlier, Salomon was “an itinerant salesman who went into the countryside to sell his wares and returned on weekends to Tarnow.” Again, this additional piece of information sounded very much consistent with the description made by Shmuel Braw regarding Zalman Maurer, one of the “frachters” from Tarnow. An image of the book’s title page may be viewed below: The book’s complete title and publication information translates as: Don’t Be a Good Young Man! An Entirely True Tale, Peppered with Humor. As Well As a Poem, an Illustration-of-Life of a Traveler. Separate Addenda of All the Farmers’ Markets in Galicia. The Storyteller Who Is Renowned Everywhere: Zalmen Moyrer [Salomon Maurer], Tarnow. Published by O. M. Wolf, Tarnow, 1925 YIVO possesses the only copy of Salomon’s book that has thus far come to light. Knowing the book was at YIVO, Russ contacted his brother, Ed, who lives in the New York metropolitan area, and asked him to go to YIVO and scan the volume. Once that task was complete, I would then be able to begin the actual translation work on the Yiddish text, about which I was now more than a little bit curious and quite eager to read. When Ed Maurer requested the book from the YIVO librarian, he was handed two copies. As it turns out, Salomon had also authored another book in 1911 with the same title, but slightly different subtitle and different publication information. The image of the 1911 book’s cover page, may likewise be viewed here, as can the translated title, subtitle, and publication information:  Title page of Salomon Maurer’s 1911 publication, which was discovered by Ed Maurer during his visit to the YIVO Institute, NYC (photo credit: Ed Maurer). Title page of Salomon Maurer’s 1911 publication, which was discovered by Ed Maurer during his visit to the YIVO Institute, NYC (photo credit: Ed Maurer). Don’t Be a Good Young Man! An Entirely True Tale, Peppered with Humor. As Well As a Poem, an Illustration-of-Life of a Traveling Salesman. Separate Addenda of All the Farmers’ Markets in Galicia and Bukovina. The Storyteller Who Is Renowned Everywhere: Zalmen Moyrer [Salomon Maurer], Tarnow. Series I. Riglitz [Ryglice] Price 60 Heller Through the transmission of 70 Heller in postage stamps, one may receive this book delivered free of postage Property and publication of the publishers: Salomon Maurer, Tarnow, Zdrojowagasse Nr. 11. Reprints forbidden. 1911 Published by S. L. Deutscher, Podgorze The two volumes – one (the 1925 publication) being a collection of stories and the other (the 1911 publication), a single storyline – were clearly different in terms of their content. Nonetheless, both were amusing, witty, charming, captivating – and at times, even racy and bawdy – in their own right. In addition, both incorporated numerous elements of Jewish religious and ritual practices and terminology stemming from Jewish textual sources such as the Torah, Psalms, the Talmud, and various other rabbinic texts. On my part, this required researching expressions and terms in Hebrew, Yiddish, and Aramaic – not to mention in a few Slavic languages, German, and in French – all thrown in for good measure. Suffice it to say that my years of Jewish day school education proved exceptionally invaluable in translating Salomon Maurer’s texts. Yet at the same time, these works were also a satire on and a critique of society – Jewish small-town society, in particular, as well as of the so-called high society life of the big city. Furthermore, they demonstrate the changing ways of the world, both in the pre-World War I era and in the interwar period in Central-Eastern Europe, the region in which these stories are set. Hence, we encounter, for example, in the 1925 volume, a few pages that go into painstaking detail about the latest styles and modes of women’s fashion – many of them imported from France – especially, as suited a specific bride-to-be on and shortly after her wedding day. In this instance, the big-city is Tarnow, the nearest urban center, to which the said bride-to-be and her mother plan to make a four-week-long shopping spree. In a similar vein, we encounter in the 1911 text, the vast distinction between provincial Galician life and sophisticated Austrian life as it played out within the first few years of the former century. This may be seen through the eyes of the naïve schlemiel protagonist, Shmuel of Ryglice, Poland (a town situated near Tarnow), as he travels to the urban metropolis of Vienna, Austria. There, Shmuel is accompanied by somebody named Gabriel in the following scene, where his insularity and parochialism are perhaps most evident: 9 o’clock in the morning Gabriel and Shmuel begin to stride across the streets of Vienna. On the streets there is a commotion, a tumult, a fuss, a noise, a racket, a bang, a ruckus; the fiacre [drivers] with their whips, automobiles sound/ring and crash, people run, rush, grab, clamor, make a commotion, a racket; at the same time, commuter merchants – I beg your pardon – without any time to blow their nose. Every minute, our Shmuel receives a blow to the ribs from the front and from behind, such that his eyes betray him. Shmuel asks Gabriel: “Why are they running about so, why don’t they have any time; perhaps they are running to Tashlich?” In the middle of everything an automobile comes running with a beeping, and dogs run after it. So Shmuel asks: “Good-hearted Gabriel, may you be well and strong; what type of animal is this and who are these gentlemen with glasses on their faces, like my `Grandma Tsaytel,’ may peace be upon her?” Answers him Gabriel: “Those are au-to-mo-biles!” “I understand, hee, hee,” cackles Shmuel – “those are, of course, German dog beaters, and woe, how they bark!” (Salomon Maurer, 1911 text, p. 11). What a contrast this description bears when compared to the humble and lowly, yet homey Ryglice, seen in the following excerpt. Indeed, the community must have been familiar to Salomon Maurer, a native of Tarnow, whose own family hailed from a village seven miles east of Ryglice named Jodlowa. As Russ informed me, this is where all the Maurers of one or two generations earlier had originated. Not far from Tarnow is a small town and it is called Riglitz [Ryglice]. It is a town, just like all other small towns, not to complain, with all the accoutrements: with a rabbi who has a patent and a concession on begging, with a rabbi’s wife, a Tkhine-reciter, Havdoles braider, a Good Eye prodder, [candle] wick placer, grave measurer, [and] foresayer – everything [rolled] into one. There was also no shortage of [female] telegraphists, a bathhouse attendant, a synagogue clapper, a [synagogue] beadle who speaks through the nose, a town crier, jugs for Matzoh water, a Chalitzah shoe, a town madman, a social welfare organization, a police officer with a wooden sword … the water carrier, bathhouse heater, Sabbath Gentile, [and] chimney sweeper. A blessed town with waiters, plate lickers, matchmakers, [foot] corn cutters, cooks, teachers of young pupils, rabbis’ assistants, teachers’ assistants, town abortionists, the community leader – everything and anything [one might need], the entire kit and caboodle is here: a large, broad, muddy, crude marketplace, lined with noodle pins, Cholent pots, slop pails, hens, pigs, ducks, fertilizer, troughs, mounds of garbage, shovels, spools, rolling pins, [and] fire extinguishers. And shops you have of all types, [all] together in one: with Turkish pepper, spreads, kosher thread, tallow candles, buckwheat groats, horseshoes, storybooks, wicks, soap, prayer books; bread and scrap metal, sugar and Tzitzit, kosher oil and cans, rock oil and licorice. In a word, a blessed town of His “beloved name” [i.e., most likely a reference to God]. Only, slow down with that wagon shaft! You are not yet done! The small town, as little as it may be, has within it a great power, an amazing strength, as though drawn unto itself from a magnetic force, such that one stops for at least a minute in the middle of the marketplace to “marvel at the beauty of the buildings”: little chimneys, garrets, verandas; and with all the good things, yet. And try to tear yourself away. It is to no avail; the Riglitz mud has such a magnetic force, that a galosh or slipper must die a violent death in the mud… (Salomon Maurer, 1911 text, pp. 3-4). There is much more that could be related here about the various accounts – fictional works that were presumably steeped in reality – conveyed by Salomon Maurer in his tongue-in-cheek manner in his 1911 and 1925 publications. But in the interest of space, I will conclude here. I hope that these excerpts have provided a tempting forshpayz (literally, an “appetizer”) for the broader literary talents and repertoire of our author. I also hope that Russ – as he shared with me a few weeks ago – will soon have the opportunity to present some of his late relative’s writings in an adapted public reading before a high school audience, so that Salomon Maurer’s genius can ultimately have its day in the limelight and be shared with yet another, younger generation of literary recipients. Somehow, this seems to be a very befitting way of memorializing our author – one that I trust would bring him much inner satisfaction and nakhes (personal joy or pride).  Salomon Maurer and three of his sisters: Yetta Maurer Kupferman (?) (kneeling in front); Regina Maurer Trieger (to Salomon’s rear); and Marumcha (Mary) Maurer Stechler (opposite of Salomon and to Yetta’s rear), surrounding the headstone of their late father, Rabbi Jacob Maurer (1844-1917) and Jacob’s father-in-law, Shlomo Zalman Feldman (died 1856), Tarnow, Poland, c. 1931 (Thanks to Russ Maurer for providing this photograph.)  Group portrait of Alan Golub, his wife, Dorothy, some of the Holocaust survivors he aided at the close of World War II, and their family members. Sari Gruenzweig, the seamstress mentioned in the article, is seated directly to Mr. Golub’s left rear side. Also depicted are Esther Epstein (seated in the rear center) and Lea Singer (seated next to Mr. Golub, holding the original group portrait from 1945). (Pesach Tikvah, Brooklyn, New York, Mon., October 26, 2015). (Photo credit, Abby Sullivan). Group portrait of Alan Golub, his wife, Dorothy, some of the Holocaust survivors he aided at the close of World War II, and their family members. Sari Gruenzweig, the seamstress mentioned in the article, is seated directly to Mr. Golub’s left rear side. Also depicted are Esther Epstein (seated in the rear center) and Lea Singer (seated next to Mr. Golub, holding the original group portrait from 1945). (Pesach Tikvah, Brooklyn, New York, Mon., October 26, 2015). (Photo credit, Abby Sullivan). Several weeks ago I was put in touch with Eve M. Kahn, the Antiques columnist for the New York Times. Eve was in need of a Yiddish interpreter, somebody who could serve as a liaison in helping to track down a small pool of Hungarian Jewish Holocaust survivors who today reside in Brooklyn, New York. These women were all part of a larger group of 34 women whose lives were literally saved during the final days of and shortly after World War II by a United States Army pilot named Alan Golub who had helped liberate the Buchenwald concentration camp. Mr. Golub provided the starving and half-naked women with “appropriated” food and coal from the commissary at the local air base – and fabrics – acquired at gunpoint from a recalcitrant shopkeeper. At the time, the women were all living in a schoolhouse in Eschwege, in central Germany. Mr. Golub, 91, who is also Jewish – the son of Eastern European immigrants – was able to communicate with and mollify the terrified women in their common mother tongue: Yiddish. Thanks to him, one of the women, Sari Gruenzweig, a trained seamstress, was able to make matching dresses for herself and several of the women. All of these women were immortalized in a portrait taken of them on July 1, 1945. The matching dresses may be clearly viewed in this photograph. In the center of the women stands U.S. Army Chaplain, Rabbi Robert Marcus (1909-1951), who served with the rank of captain during the Second World War. He was among the first to enter liberated Buchenwald, Dachau, and Bergen-Belsen. Alan Golub donated his own original copy of the photo in 1999 to Yad Vashem, Israel’s official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust. That copy was inscribed on the verso with the women’s names and a note thanking Mr. Golub for all that he had done. Eve’s original plan was that we meet with these Holocaust survivors individually in their homes and reunite them one by one with Alan Golub, whom the women had affectionately called “Gub Gub.” As such, it was my job to start making phone calls to the women whom Eve and Gary R. Sullivan, Alan’s son-in-law, had managed to trace with the help of researchers in Hungary, Germany, and in Israel, at Beit Hatfutsot (the Museum of the Jewish People). Admittedly, this was not as easy a task as one might have anticipated, seeing as all of these women are now into their 90s, are hard of hearing, and in a generally frail state. One woman with whom I spoke said that she did not want to be interviewed about anything pertaining to World War II, because she had previously been interviewed and it had been such a trying experience, that it left her emotionally distraught for days. She could not bear undergoing another such similar experience. What’s more, she remarked that she had never spoken to her own children about her experiences, since she did not want to burden them with the hardships and horrors of her earlier life. In another instance, I spoke with the son of one of the women, who informed me that his mother was in the hospital and would most likely not be in any condition to meet with the former pilot. I also learned from the son that he knew of the other women who had been together with his mother following the war, but that many of them had already died or were most likely too sick or infirm to meet with Mr. Golub. Inwardly, I was beginning to lose hope of our being able to find women from this dwindling group of Holocaust survivors who would be able to meet with us and Alan Golub. I reported back to Eve about what I had learned from my phone calls – some of them, made multiple times to the same unanswered number. It was only a few days before we were supposed to meet on Monday, October the 26th. The plan was to have Eve, Alan and his wife, Dorothy, Gary Sullivan, and his wife – Alan’s daughter, Abby Sullivan, a photographer – and me, present. We were going to drive around, stopping off in Williamsburg, Boro Park, and Midwood/Flatbush – all neighboring sections of Brooklyn, in which the women presently make their homes. Alan and his extended family would be driving all the way from the Boston area, so this was quite a “big deal,” as far as they were concerned. About a week before the meet date, Eve wrote me to ask if I could recommend any venues that she might contact – any newspapers or institutions that particularly targeted Holocaust survivors and their offspring – as she was still eager to learn what had happened to all of the women in that postwar group portrait. I wrote up a list of different institutions and newspapers that I thought might be relevant, which included the American Gathering of Jewish Holocaust Survivors and Their Descendants, which publishes a newsletter called “Together,” GSI (Generations of the Shoah International), which publishes a widely-circulated online newsletter, and the Pesach Tikvah Jewish social welfare organization, based in Williamsburg, which provides services to Holocaust survivors, among other members of the local Jewish community. Since I work part-time for the latter institute running a translation workshop for female Holocaust survivors – all of them from what was formerly Hungary – I was already personally familiar with the types of individuals serviced by Pesach Tikvah. I figured that this would be a good contact for Eve, since the women she was interested in were all Hungarian and had been from religiously observant backgrounds. The Ultra-Orthodox and heavily Chasidic Jewish community of Williamsburg, I might add, is predominantly Hungarian in its makeup. In less than a week before our scheduled meet date, Eve sent out a jubilant email to Gary and me, entitled, “Breaking News…,” in which she related the windfall she had had that very day by speaking with Ruchie Lichtenstadter, the Volunteer Coordinator at Pesach Tikvah. As it turns out, I know Mrs. Lichtenstadter from the translation workshops that I run; she assists me in helping the women to better transmit their translations in the written word. But what I did not realize was that she is also related to some of those women in the photograph from 1945. Indeed, she is a relative of the aforementioned seamstress, Mrs. Gruenzweig. In addition, she is knowledgeable about what happened to other women in that photograph, and is in contact with their offspring. As such, Mrs. Lichtenstadter made a series of calls, spoke to the directors of Pesach Tikvah, and the decision was made that their organization would host the reunion for the Holocaust survivors and Mr. Golub. Furthermore, an all-out celebration of sorts was in the works. Neither Eve, Gary, nor I had any real conception of what this meant until we all ultimately met at Pesach Tikvah, less than a week later. Lo and behold, there were over 100 people in attendance at this once-in-a-lifetime reunion, held some 70 years after the fact. Everyone was crowded into three smallish-to-medium-sized rooms, in which Mr. Golub was regaled with singing and blessings upon blessings in Yiddish, Hebrew, and English by the family members of the Holocaust survivors. The crowd wished him that God should reward him for all that he had done on behalf of these women, and that he should have good health and live until 120 – in Yiddish, “Biz a hundert un tsvontsik!” Another well-known Jewish adage that was uttered multiple times in conjunction with Mr. Golub, is: “He who saves one life saves an entire world.”