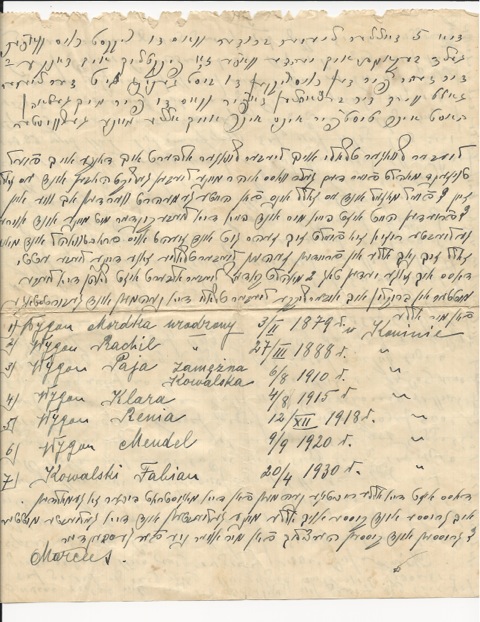

Hal Melnick’s father and grandmother, Albert and Esther Melnick (circa 1920s). The letter that I translated was for many years concealed behind this photograph. Hal Melnick’s father and grandmother, Albert and Esther Melnick (circa 1920s). The letter that I translated was for many years concealed behind this photograph. A few weeks ago a Math professor named Hal Melnick contacted me with an almost novel-esque account of how he came to find a long-lost letter that had been sent to his late father, Albert, then residing in the US, by his sister and brother-in-law, who continued to reside in the family’s ancestral town of Konin, Poland. It is also worth mentioning that this letter dated back to shortly before the outbreak of World War II – indeed, according to Melnick – to 1939. Germany declared war on Poland on September 1, 1939, so this window of time is in itself quite significant. As Melnick related to me, shortly after the invasion of Poland, “the entire family was killed.” Amazingly, Melnick happened upon the well-concealed letter behind – in his words: “a beautiful picture of my father and his mother attending my aunt’s wedding. This picture had been hanging in my parents’ home for 40 years, and in mine, for the past 20, since their passing.” Melnick’s hope was that by translating this recently uncovered letter, I would be able to help shed some light on his family’s final days in Konin, and provide “some insight into their thinking.” Melnick also later added the curious note that along with this letter, was clipped a lock of his late grandmother Esther Melnick’s hair from the time she was 80 years of age. And yet, according to Melnick, it was not even grey! One of the additional rankling points for Melnick was that his Konin relatives – most of whom bore the surname, “Wygom” – continued to remain so elusive to him. In his words, “When I try to search the Wygom name in any of the Holocaust museums I have visited, I never come up with anything. It continues to be a mystery, since I know they lived in Konin and were all victims of the Holocaust. Meanwhile, I am deeply interested in reading the translation of these two pages. It is all we have.” The letter itself bore a rather Germanic Yiddish, which, as I explained to Melnick, was not so unusual, considering that Konin is situated in what was western Poland – toward the German border – on the eve of World War II. Rather unique for me was the fact that the letter’s primary author – a relative named “Marcus” – had compiled a list of family members, along with their dates of birth. All of them had been born in Konin, and the information had been obtained, according to the author, from the town hall’s magistrate books. Nearly every one of those individuals listed bore what appeared to be the surname that Melnick had mentioned to me: “Wygom.” However, upon closer examination, I was uncertain whether this was the correct surname, after all. Perhaps it was because of my former work as an archivist at the YIVO Institute with documents that hailed primarily from Poland – as well as my two years’ of Polish language courses and multiple trips to Poland – that I had a hunch that “Wygom” was actually “Wygon.” I also thought that perhaps this would help account for why Melnick had never been able to successfully locate this surname in conjunction with Konin. In either case, I decided to take this translation “stuff” one level further and research what I believed was the correct version of the family name. After all, my goal was to provide as accurate a translation of this letter as possible. My research took me to the Yad Vashem Central Database for Shoah Victims’ Names. Once there, I plugged in the surname “Wygon” – with an `n’ – and not an `m’ – and the city name: “Konin.” Voila! I received 33 hits, all of them individuals whom I believe were Melnick’s relatives. What’s more, I found at least one match when I compared the names and birth dates in the Yad Vashem listing alongside the list of names and birthdates included within the letter. The match belonged to a woman named “Paja Wygon Kowalska,” also known as “Pesia” / “Pessa” and “Pola.” On the Yad Vashem website, the name appears both as “Pesia Pessa Wygon” and “Pola Kowalska.” All of these individuals – almost certainly one and the same – were born in Konin in 1910. Melnick was also intrigued by the listing of family names and dates of birth in the letter, which “Marcus Wygon” (as it turns out) had taken the time to research and record – possibly, for posterity. Just prior to this listing, he mentions the fact that he is now reciting the Kaddish (i.e., the Jewish prayer to memorialize the dead) twice, daily. Melnick wondered whether this combination of elements: the recitation of Kaddish for a recently departed family member (name not indicated in the letter), the listing of family members’ names and dates of birth, along with the fact that this letter was mailed abroad to other family members just shortly before the Holocaust, was perhaps a sign that Marcus Wygon saw the handwriting on the wall of what would soon befall the Jews of Konin, and more specifically, his own extended family. Of course, at this late date in time, one can only surmise what was going through the mind of Marcus Wygon and countless other Jews like him. But although this letter writer presumably did not survive the Holocaust, still, he had the foresight to commit these important details to paper and to send them to relatives who had had the good fortune of finding a safe haven overseas, in the US. In this manner, he helped insure that surviving future generations of the Wygon family would have the names of those family members who had not survived, those for whom Kaddish was to be recited.

6 Comments

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed