|

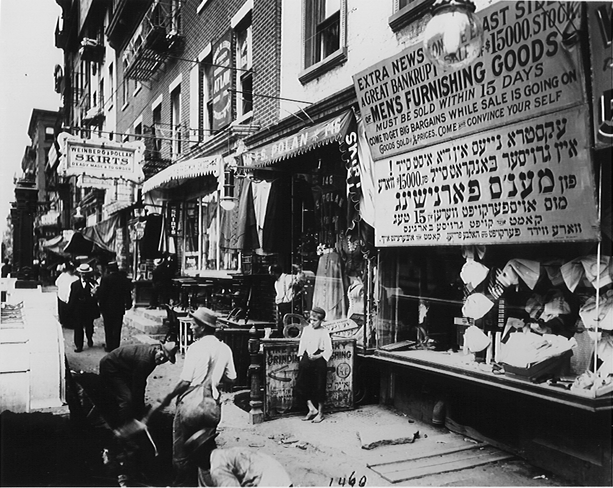

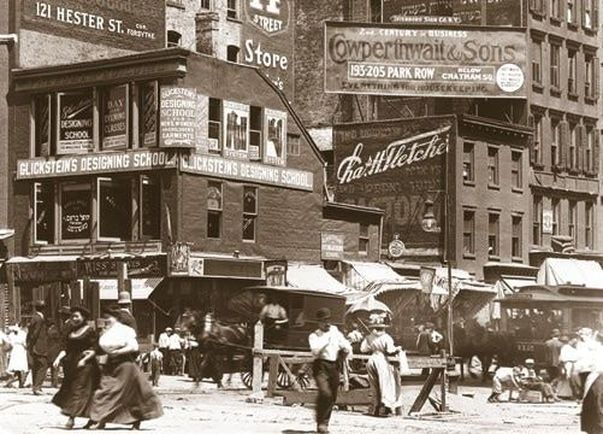

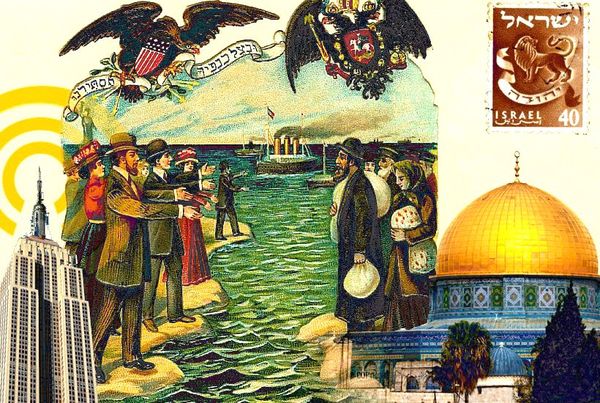

My clients often ask me about the type of themes and subject matter that I encounter in my unusual line of work. In the nearly twenty years since I began translating Yiddish texts, I have definitely found certain themes that are relatively common and widespread among family letters, in particular. In thinking this over recently, I was able to break down those frequent topics of correspondence into the following general groups: 1. Shortages of money and/or food – This is especially prevalent in letters written in Eastern Europe during times of economic depression, and/or warfare (e.g., World War I and II). Since many of the letters I encounter stem from the interwar period, I can say without question that these hardships become increasingly pronounced during the final years and months leading up to The Second World War. In certain instances, this coincides quite blatantly with the anti-Jewish laws that were enacted against Jews in large swaths of Eastern Europe. 2. Instructions regarding maintenance of the family business – Be it about business conducted in Europe (the proverbial “Old Country”) or already in the United States, South America, Palestine – “Eretz Yisrael” – or elsewhere (the proverbial “New Country”), this is a theme that frequently repeats itself – generally between fathers and sons, brothers, and other male family members. Only in rarer instances have I seen female family members included in these financial discussions. 3. Hope that the family will soon be reunited in the “New Country.” In the current state, the family is fragmented, divided between different continents – the “Old Country” versus the “New Country.” Occasionally this division is simply between different cities within the “Old Country.” It is entirely common to find the “Almighty’s” name invoked here. Many parents and grandparents (and other family members) often write something akin to: “I hope that the blessed Lord will help me in seeing you in-person, once again.” Sometimes the invocation is even more dramatic and imploring: “May I still lay eyes on you one last time before I depart this earth.” 4. Illness and death – References to family tragedies and misfortunes are not wholly uncommon. Usually these subjects are mentioned in conjunction with the worsening physical state of a parent or grandparent (or other close relative) and/or news of his/her untimely death. Sometimes this is clearly linked to the generally nefarious condition for Jews in Eastern Europe prior to (and leading into) the Holocaust. At times, when the letter is directed at a son, he is entreated with the responsibility of saying Kaddish (the Jewish prayer for the dead) and observing the seven-day period of Shiva (the time allotted within traditional Judaism for mourning). Traditionally, it was the obligation of the son/s to recite Kaddish for a year following the death of a parent. 5. Maintenance of religious traditions, primarily in the migration from the “Old Country” to the “New Country.” It was well-known that America, in particular, was not so much the proverbial “Goldene Medine” (Golden Land) - referenced by the likes of Jewish immigrant writers such as Anzia Yezierska (1880?-1970) in Hungry Hearts and other related works. Rather, for many Jews, America represented the “Treyfe Medine” (Unkosher Land) – at least for those Jews who continued to adhere to traditional, religiously observant Judaism. This realization on the part of Jews who remained behind in the “Old Country” regarding the decline of religious observance set in as early as the turn of the previous century. What’s more, it lasted right up until the outbreak of World War II. This is reflected in several letters that come to mind from the interwar period, usually written by admonishing parents to their children who had already immigrated to the “New Country” (mostly, from the letters I have translated, the United States).  “New Country”: Scene of the Lower East Side of New York City, turn of the 20th Century. Note that none of the adult males depicted here – many, if not all of them, likely Jewish immigrants – have beards, a typical mark of a religiously observant adult Jewish male. Also note that in many cases, business and shop signs bear Yiddish advertisements (sometimes, without the accompanying English translation). (Courtesy of the Tenement Museum New York: goo.gl/1Ob7Xw, accessed 12-31-16.) Anecdotally speaking, I will never forget a vignette my grandfather related to me vis-à-vis the perceived decline of observant Judaism in the “New Country,” in contrast with that of the “Old Country.” According to my grandfather, who was born in Kielce, Poland in 1904 – prior to such historical events as the sinking of the Titanic (which my grandfather recalled) and World War I (which, for some reason, my grandfather never mentioned to me) – there had been a local Jew in his community who had actually “gotten out” before World War II (my grandfather’s words) and come to America. Yet unbelievably, he returned to Kielce sometime during the interwar period, because as he informed the local Jewish community, it was impossible to maintain one’s “Yidishkeyt” (observance of traditional Judaism) in the “New Country,” as it was entirely “treyf” (unkosher). Cases in point of this growing religious divide between the older generation in the “Old Country” and the younger generation in the “New Country” may be seen for example, in some of the entries in the Forverts' /Yiddish Forward’'s advice column, known as “Dos Bintel Brief.” The column, which in Yiddish, literally means “The Bundle of Letters,” ran for over 60 years (from 1906 until at least 1970), and doled out various forms of advice regarding the struggles and woes of Jewish “greenhorns” – and their offspring – in the United States. The following abbreviated excerpt is but one such case highlighting this very divide: 1908 Worthy Editor, I have been in America almost three years. I came from Russia where I studied at a yeshiva. My parents were proud and happy at the thought that I would become a rabbi. But at the age of twenty I had to go to America. Before I left I gave my father my word that I would walk the righteous path and be good and pious. But America makes one forget everything. Here I became an operator, and at night I went to school … entered a preparatory school, where for two subjects I had a Gentile girl as teacher… I don’t know what I would have done without her help. I began to love her, but with mixed feelings of respect and anguish … and I never imagined she thought of marrying me… Then she spoke frankly of her love for me and her hope that I would love her… I was confused and I couldn’t answer her immediately. In Europe I had been absorbed in the yeshiva … She is pretty, intelligent, educated, and has a good character. But I am in despair when I think of my parents. What heartaches they will have when they learn of this! I asked her to give me a few days to think it over. I go around confused and yet I am drawn to her. I must see her every day, but when I am there I think of my parents and I am torn by doubt… Respectfully, Skeptic from Philadelphia (A Bintel Brief, edited and with an introduction by Isaac Metzker. New York: Ballantine Books, 1972, pp. 77-78.) In contrast to the above categories, I may also add here – should the reader be wondering about themes that are scarcely discussed in the letters that I have translated – that I have a brief list, as seen in the following: 1. Serious financial corruption and fall-out within families; 2. Family members marrying outside of the Jewish faith; 3. Marital indiscretions, illegitimate births, abortions, and the like. Perhaps not surprisingly, this category, as well as the previous one, are typically referred to in rather euphemistic terms. I would like to focus on the last category of my most frequent themes in my current blog (“Maintenance of religious traditions”), as it is a subject that has appeared with greater recurrence in letters that I have translated recently. In order to shed further light on this phenomenon, I shall provide one excerpt here from some of these letters – to be continued (ideally) in my next month’s blog. However, in order to honor the privacy of my client, names have either been omitted or changed here. p. 1 With God’s help November 25, c. 1920s, Podgórze (Kraków) Dearest daughter, Lea, I received your letter today. Your words shook my heart, such that I could not calm down from crying. I had joy and suffering. For every word, I wished [you] well; that everything should always go well for you, and that my eyes should yet see you. For you recognize your sin. Therefore, the blessed Lord will forgive you; and I forgive you, as well. I am very glad that you are living a Jewish lifestyle. The blessed Lord will always help you… p. 2 …. And that which you write, that Rifke says that since you write, she need not also write … Were she still to have feelings toward her parents. But I see that her feelings have already been extinguished. The most significant thing is that she does not live a Jewish lifestyle, so she has no heart to write her parents. She must wrangle with the fact that nobody lives forever; not be [unduly] proud about her little house, seeing as her father had more than she has. And she did not take anything with her, now that she had an opportunity to do penance [i.e., for the sins/wrongdoings she did to her parents and in not living a Jewish lifestyle] and left it to you [i.e., that “you” should be responsible for writing, since she has no heart to do so]. Thus, I do not envy her. As I learned from my client regarding the above excerpt, which I translated from a larger body of text, the author of this letter was a very pious woman. Several of her children were already living in the United States at the time when she wrote these words to one of her daughters. The author, known by her descendants as “Bubbe [Grandmother] Dina,” was quite adamant that her children maintain their religiously observant lifestyles – regardless of whether they were now living in a more “open” and less Jewish environment overseas. What disturbed her most, though, as my client related, was that one of her daughters – Rifke – had decided to marry a man who was not religiously observant. The family’s oral tradition was that Rifke had always been “the rebellious child” – the one who had distanced herself from the rest of the family, stopped observing the Jewish Sabbath, keeping kosher, and the like. As such, my client was not in the least bit surprised to read (in translation) these admonishing words of “Bubbe Dina” regarding Rifke’s not living a “Jewish lifestyle.” The above letter excerpt – translated from the original Yiddish – is but a small window into the types of subject matter that I frequently encounter in my work as a Yiddish translator. In my next blog, I will pick up this subject again – and possibly some of the other themes I mentioned above. As one can see from the words expressed here, there was an evident growing divide – certainly along the lines of religious Jewish observance between the older and younger generations, even within close-knit families. This divide was all the more blatant when the older generation (that generally constituted the authors of the letters that I receive) still remained behind in the “Old Country” and the younger generation had already immigrated to the “New Country.” I would imagine that many of my readers are familiar with this phenomenon within their own families. As such, I invite you to please share you own accounts of this particular theme in your comments following my blog post. I am always interested in and intrigued by reading about such family “sagas” in my work as a Yiddish translator.  “New Country”: Delancey and Essex Streets on the Lower East Side of New York City, c. 1908. This was formerly one of the most prominently Jewish immigrant neighborhoods in all of New York. Faint Yiddish advertisements may be seen in the background. (Courtesy of Old NYC Photos: oldnycphotos.com: goo.gl/jr5agn, accessed 12-31-16.) Should you have any such family letters pertaining to any of the subject matter discussed here or beyond that you would like translated from the Yiddish, please do not hesitate to contact me at: [email protected].  “Old Country, New Country”: Illustration that may be interpreted to represent the stark contrast between the “Old Country,” as demonstrated by the lone traditional Jewish shtetl fiddler situated amidst the large and looming urban landscape of the “New Country” (in this case, New York City). (Courtesy of Timeline Touring: http://timelinetouring.com/images/fiddler.jpg, accessed 12-31-16.)

17 Comments

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed