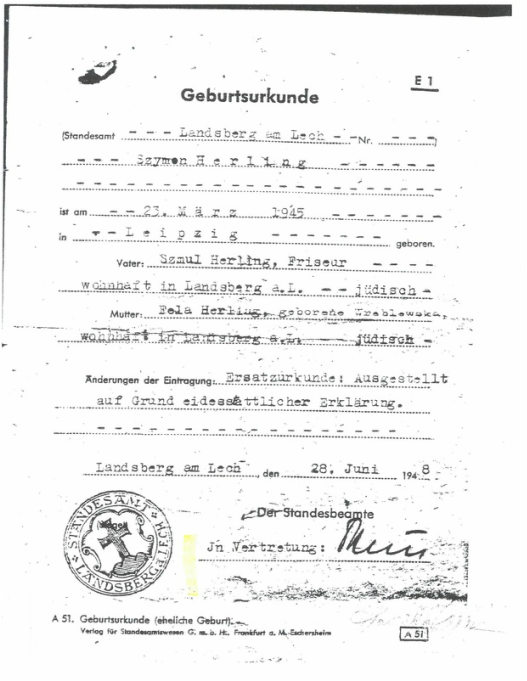

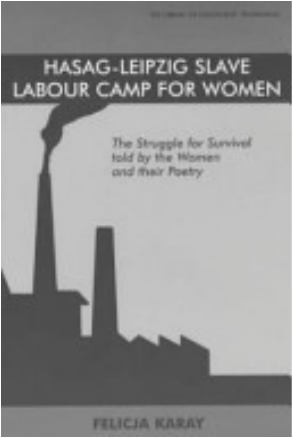

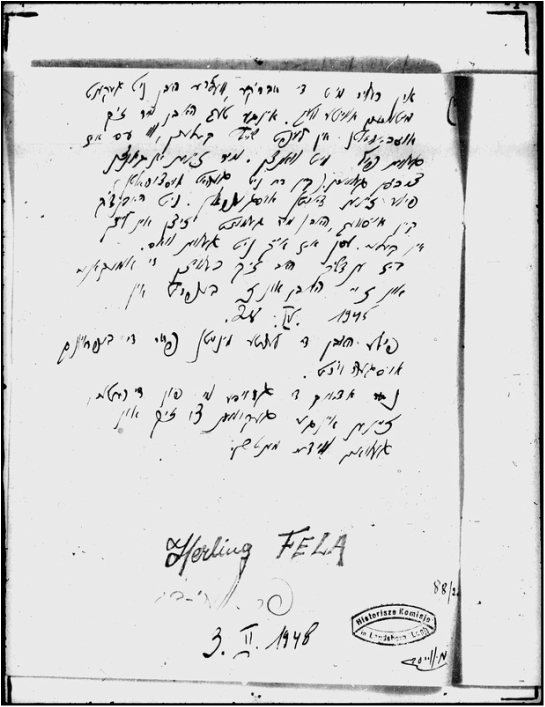

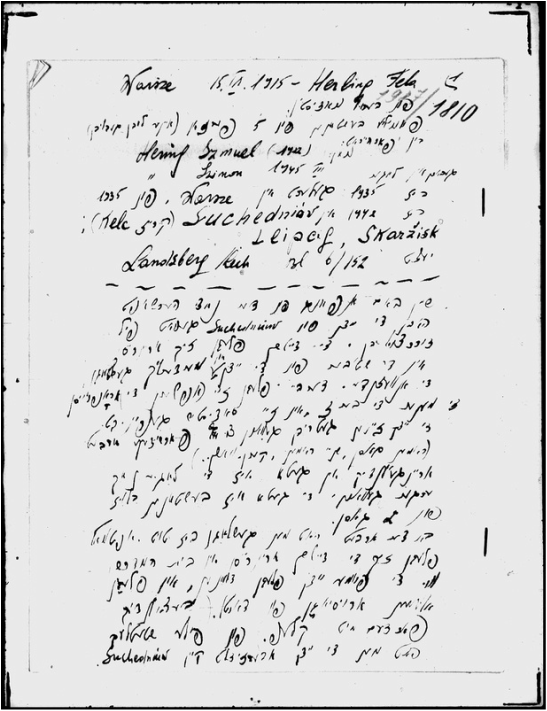

Birth certificate of Simon [Szymon] Herling, born to Szmul and Fela Herling in Leipzig, Germany, on 23 March 1945. Issued on 28 June 1948 in Landsberg am Lech, Germany, where the Herling family resided in a D. P. camp following World War II. No specific mention is made here to the fact that Simon Herling was born in a German concentration camp. (Thanks to Simon Herling for providing me with this scan of his birth certificate.)  The book by Felicja Karay that makes explicit reference to Fela Herling and the other women who gave birth to infants in the Leipzig-Schönefeld concentration camp (http://goo.gl/pUv2bG). The book by Felicja Karay that makes explicit reference to Fela Herling and the other women who gave birth to infants in the Leipzig-Schönefeld concentration camp (http://goo.gl/pUv2bG). When I first made the acquaintance of Simon Herling, the individual who was born in a concentration camp, whom I wrote about a few months ago in my November blog, "Miracle Birth in a Concentration Camp," I never would have imagined what a positive domino effect that would have on Simon, me, or on other people, for that matter. Ever since I read his Yiddish article from 1958 relating the circumstances of his birth and making reference to other surviving infants born in the Leipzig-Schönefeld concentration camp (a sub-camp of the better known, Buchenwald concentration camp), I have been on a mission to find out who those other infants were and what their ultimate fate was. The odds of children being born in Nazi concentration camps and surviving World War II were so slim, that I was significantly moved by this account. So much so, that I wanted to employ my research-detective skills to follow through on this story, wherever it would ultimately lead. Here is how this positive domino effect series of events has unfolded, thus far: A few days after I posted my blog about Simon, I was contacted by a representative of the British online newspaper, The Independent, who asked me if I would allow the newspaper to reprint my article, “Miracle Birth in a Concentration Camp.” Dina Rickman, one of the newspaper’s employees, is a former client of mine and receives my blogs. When she saw my piece, she thought it might be of interest to her newspaper. The timing of things also worked out well, as Kristallnacht (literally, “Crystal Night” or loosely, “Night of Broken Glass”) fell out right around that time, in early November. With Simon’s approval, I agreed to have the article reprinted. A few days after my article was reprinted in The Independent under the following title: "How a Jewish Woman Survived Pregnancy in a Nazi Concentration Camp to Give Birth to Her Son," I received a most unexpected long-distance phone call from Germany – the Buchenwald Memorial Site – of all places. The young woman who phoned me identified herself as Mackenzie Lake, an American doing ecumenical volunteer work at Buchenwald for the year. She was calling in regard to my article, she said, as the Buchenwald Memorial Site was eager to get in touch with Mr. Herling. They wanted to invite him to the Holocaust survivor gathering their museum would be having in April 2016. Since I now had this unforeseen connection to Buchenwald, I told Mackenzie that I was on a mission to find out what had happened to the other infants who had apparently been born in the same concentration camp as Simon and survived the war. Mackenzie informed me that she would see what she and her colleagues could find in their files onsite; and at that point, we left off that we would be in touch. After I got off the phone with Mackenzie, I immediately followed up with Simon, gave him Mackenzie’s contact information, and let it go at that. I was quite hopeful that Simon would find the wherewithal to attend this event – especially, seeing as he would be one of – if not the very youngest survivor – in attendance there. As I learned more recently from Simon, who in turn spoke with Mackenzie, at the present time the Buchenwald Memorial Site foresees having roughly 40 Holocaust survivors who were incarcerated within the Buchenwald concentration camp network in attendance, this coming April. Furthermore, in one of my most recent telephone conversations with Simon, he informed me that he does indeed plan to attend the gathering at Buchenwald, in the company of his daughter, and visit the site of the concentration camp in which he was born. A few weeks after all of these exchanges, I received an email and book scan from Mackenzie stating that after some serious digging, she and her curator and archivist colleagues, Dr. Harry Stein and Sabine Stein, had located some relevant-sounding information about the women who had given birth in the Leipzig-Schönefeld concentration camp at the tail end of World War II. Felicja Karay, in her scholarly work, Hasag-Leipzig Slave Labour Camp for Women (Vallentine Mitchell, 2002), states the following (page 163): Some women who had been brought to the camp in the early stages of pregnancy had disregarded orders and not registered. Hanka Kurtz worked in the plant throughout her entire pregnancy, and was lucky enough to receive a great deal of help from her German manager. Fela Herling was able to hide her pregnancy for eight months, but since she appeared to be plump and healthy, she was assigned the harder tasks. Until one morning a woman in her block went into labor. As a result, it was announced at roll-call that if all the pregnant women did not report, the entire block would suffer collective punishment and the offender would be hanged. Herling reported, and three weeks later gave birth to a son in the Revier. She was placed on a transport list, but the train could not be sent out because the Front was now too close, and thus she was saved. The night before the camp was evacuated, Hanka Kurtz gave birth to a daughter, and both mother and child survived. The fate of the other woman Mirka (last name unknown), who gave birth is not known. At around the same time Róźka Millstein also had a child and remained in the camp after the evacuation thanks to a bribe the Polish prisoners gave to the SS overseer. What came to light from the above passage that Mackenzie emailed me were both actual names of women who had given birth in the Leipzig-Schönefeld concentration camp – something that had been entirely unknown beforehand – as well as an important reference to Fela Herling, Simon’s mother. Important, because the reference provided a footnote indicating that Fela had provided a testimony about her wartime experiences to Yad Vashem, the leading Holocaust memorial site in Israel. I forwarded all of this information to Simon, and just as I had suspected, he had had no knowledge of his mother’s testimony until now. I informed Simon that I would do my best to track down a copy of his mother’s testimony, hopefully, within the United States. The following day I phoned the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D. C. and spoke to an extremely helpful reference librarian there named Ron Coleman. When I provided Ron with the citation to the testimony as it appeared in Karay’s book, he was immediately familiar with the format and was able to confirm that the museum does indeed have a digitized duplicate of the text, which he subsequently emailed me as we were still chatting. My hunches about the testimony were correct: it was taken down by hand in Yiddish in the Landsberg D. P. camp where Simon and his parents resided following World War II, in 1948. Right away, I forwarded the testimony to Simon, and before long, he had asked me to translate this text for him. Interestingly, this testimony was given by Fela Herling a decade prior to the interview she later gave Asher Penn for his article in the Yiddish language newspaper, Der Tog-Morgen Zshurnal/The Day-Jewish Journal, which I translated for Simon and wrote about here a few months ago. I knew that one of the gnawing questions Simon had always had was the fate of his older sister, who had sadly perished in the Holocaust at a tender age. As it turns out, the testimony did provide some insight into his sister’s fate, although her actual name is not mentioned in the text. Perhaps it was simply too painful and raw at the time for Fela Herling to explicitly mention her murdered daughter’s name. According to Fela’s statement, shortly before the Aussiedlung – or forced resettlement under the Third Reich – of Suchedniów, the town in which she, her husband, and child resided prior to the outbreak of the war, it became so terrible, that those who were to go do [forced] labor in a munitions factory in Skarżysko HASAG [were told] that the ones who reported [for forced labor] would survive. (8 kilometers from the town). Young people were able to report, people, families without children. I, my husband, and child planted ourselves beside the vehicle, so as to be taken to do [forced] labor. The Germans only selected young people. The Obersturmführer stood by, observing how people were being sorted. When he saw me, my husband, and child, he threw the child to the side, and pushed us into the vehicle. I attempted to jump from the vehicle and remain with my child, but the Sturmführer beat me up with a slap and pushed me back in. That is how I became separated from my child. Two weeks following that, the Aussiedlung took place (on Yom Kippur), in the town of Suchedniów. Everyone was deported to Treblinka.  The first and last pages of the six-page Yiddish testimony of Fela Herling recorded on February 3, 1948 in the Landsberg D. P. camp in Germany. (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Record Group 68.095M, “Testimonies (M.1.E)”; YVA M.1.E/1810). (Thanks to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D. C., Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, Israel, and to Simon Herling, for permitting me the use of this text.) For the first time in all these years, Simon finally had a clearer sense of what had befallen his sister, who was likely either murdered in Suchedniów, or deported to Treblinka with the majority of the town’s Jews.

Prior to my translating Fela Herling’s testimony, I was in touch with yet another department of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Holocaust Survivors and Victims Resource Center, where I consulted William Connelly about the fate of the other children born in the Leipzig-Schönefeld concentration camp. He advised me to submit forms with the names of the individuals I was seeking – names that I had subsequently learned from the book excerpt that Mackenzie Lake had sent me and cross indexed in Buchenwald’s prisoner files. And indeed, that is precisely what I did. So now, it is a matter of waiting, networking, and remaining optimistic that with all of our joint international and transnational research efforts, we will ultimately learn the fate and identities of the other surviving children who were born alongside Simon Herling at the close of World War II. I hope that at some point in the not-too-distant future I will have more concrete information about all of this to share with my readers. But in the meantime, if anyone has any knowledge of these yet unaccounted for children, or any ideas or suggestions about how to locate these individuals, please do not hesitate to get in touch with me at [email protected].

7 Comments

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed