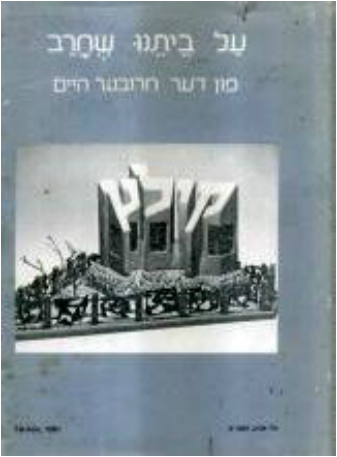

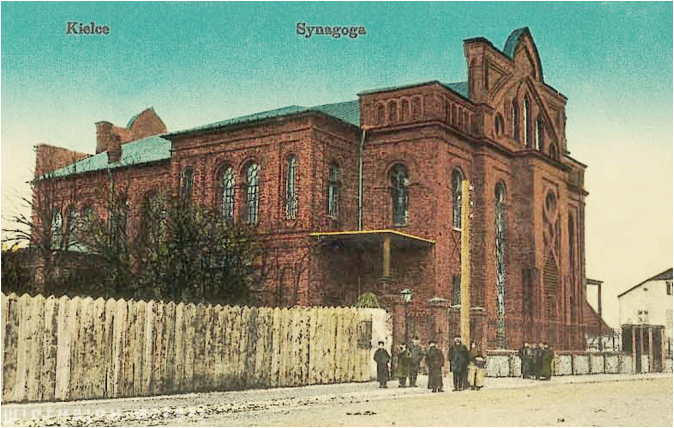

Front cover of yizker bukh, Al betenu she-harav—Fun der khorever heym [About our house which was devastated] (http://goo.gl/naZjA3, accessed 5-22-16). Front cover of yizker bukh, Al betenu she-harav—Fun der khorever heym [About our house which was devastated] (http://goo.gl/naZjA3, accessed 5-22-16). Lately, I have been thinking a great deal about landsmanshaftn and yizker bikher, both of which I will define, shortly. In the last month or so, alone, I have had more than half a dozen meetings and correspondences with clients and acquaintances to discuss the subject of landsmanshaftn in Chicago and New York City, and to translate excerpts of landsmanshaft minutes’ books – handwritten in Yiddish in the 1940s – from a landsmanshaft. This, and my own personal history vis-à-vis landsmanshaftn and yizker bikher prompted me to write this blog about those two very much intertwined subjects. A landsman [pl. landsmen] is Yiddish for “kinsman” or “countryman,” while a landsmanshaft [pl. landsmanshaftn] is Yiddish for the organization or society formed by landsmen of common towns or cities, generally in eastern or central Europe. Yizker bikher [sing. Yizker bukh] are the memorial books, frequently written by a given landsmanshaft to honor and commemorate the historical events and sundry features, characteristics, and personalities associated with its particular city or town. Many of the yizker bikher were written in the years following the Holocaust in Yiddish and Hebrew, although there are also those containing other languages, including: English, French, Polish, Russian, and Spanish. Nowadays, yizker bikher tend to be a treasure trove for genealogists, researchers, and scholars, as they include names of individuals, and very frequently, necrology lists of Jews murdered during the Holocaust. When I was growing up in Chicago back in the 1980s and early 1990s, I was used to hearing about the “Kielcers” and their various gatherings, sometimes taking note of a schedule of events clipped to my grandparent’s refrigerator door. These were the extended surrogate relatives – or landsmen – who hailed from my grandfather’s city of Kielce (pronounced `Kelts’ in Yiddish; `Keltseh’ in Polish), in Central Poland. Like my own grandparents, they were all Holocaust survivors who had immigrated to Chicago in the wake of World War II. They bore an important presence at major family functions, such as my brother’s Bar Mitzvah and my grandfather’s 75th and 90th birthday parties. When my mother was growing up, the Kielcer landsmen were an even more ubiquitous and dynamic presence in her life, since they were all that much younger, a generation earlier, and had just lost their entire world during the Second World War. As a result, most of them were eager to move forward, setting down roots in their adoptive city of Chicago, and giving rise to new and future families. In light of this milieu of transplanted landsmen in which I grew up, I had an inkling from early-on about landsmanshaftn. By extension, I was also exposed at a relatively young age to yizker bikher. Indeed, my grandfather had his own such yizker bukh, written mainly in Hebrew and Yiddish: Al betenu she-harav—Fun der khorever heym [Hebrew and Yiddish for: “About our house which was devastated”] (Tel Aviv: Kielce Societies in Israel and in the Diaspora, 1981), which I recall flipping through from time to time as a somewhat older child. It was then that my grandparents informed me of the existence of other Kielcer landsmanshaftn around the world – in far-off places such as New York, Toronto, and Israel. A few years later, when I worked at the Asher Library, part of the Spertus Institute of Jewish Studies, in Chicago, I once again had regular access to several hundred different yizker bikher. When I moved to New York City over a decade ago to work for the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, I likewise had ready access to literally hundreds of yizker bikher. As of today, I make frequent use of the yizker bikher that are now accessible online through the New York Public Library, as well as those that are accessible onsite at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Studies and the Center for Jewish History in New York City. Since relocating to New York, I have translated excerpts and the entirety of many yizker bikher written both in Yiddish and Hebrew, including the following:

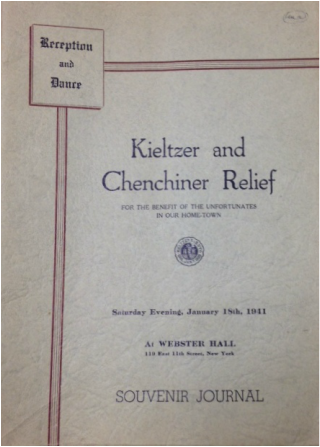

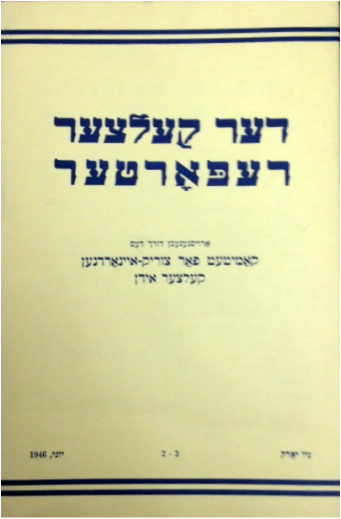

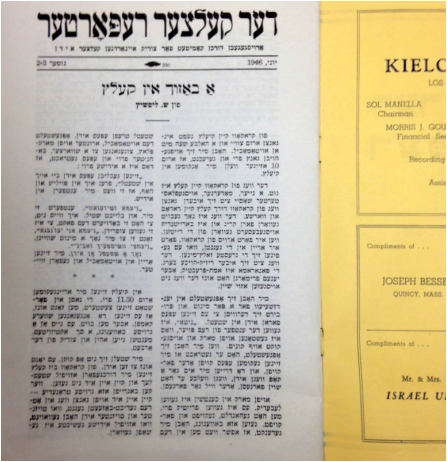

Souvenir Journal of the Kieltzer and Chenchiner Relief (later renamed the “Kieltzer Sick and Benevolent Society of New York”), January 18, 1941. (Courtesy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, NYC, RG 1056, Box 2 (of 2).) Souvenir Journal of the Kieltzer and Chenchiner Relief (later renamed the “Kieltzer Sick and Benevolent Society of New York”), January 18, 1941. (Courtesy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, NYC, RG 1056, Box 2 (of 2).) I have also surveyed and catalogued over 100 different landsmanshaft collections at the YIVO Institute, some of which may be viewed here. Among those landsmanshaft collections at YIVO that personally interested me is that of the “Kieltzer Sick and Benevolent Society of New York” (Record Group 1056), organized in New York on January 7, 1905 as the “Kieltzer Sick and Benevolent Society of Russian Poland, Inc.” The society underwent a few name changes, until finally changing its name officially to the former title in 1954. It is worth noting here that as of 2016, this is one of the few still extant landsmanshaftn in the New York City area – and probably, worldwide – that continues to meet periodically throughout the year for commemorative ceremonies and other functions. The organization, which today often goes by the more informal moniker, “The Kieltzer Society,” has its own website, which may be viewed here, and a related (closed group) Facebook site, accessible at: “Descendants of Jewish Kielce Province.” There is a great deal that may be said of the history of Jewish Kielce – particularly, about the notorious pogrom that took place there at ul. Planty 7/9 on July 4, 1946, during which over 40 Holocaust survivors from Kielce and elsewhere were brutally murdered and maimed by local residents that included police and other officials. Sadly, this is probably the one resonating reason that anybody today has ever even heard of this city. Nonetheless, it is in Kielce that my grandfather lived the first 30-some years of his life, worked as a butcher, married, and raised two sons, before the Holocaust put a roaring end to all of that. I have visited Kielce twice, most recently in the fall of 2014. On both trips there, I made a point of viewing the pogrom site and the remains of the Jewish cemetery. I have also researched and written about various aspects of Jewish life in Kielce, time and time again. One of my publications on the subject may be viewed here. Among the most haunting research finds I made while sifting through the aforementioned archival collection, is that of a Yiddish article, entitled: “A bazukh in Kielce” [“A visit in Kielce”] published in Der Kielcer reporter ["The Kielcer reporter"] in June of 1946, only a matter of weeks or even mere days before the previously mentioned murderous rampage took place (on the 4th of July). The article was written by Sh. Lipshitz, a Yiddish writer for the Vokhenblat newspaper (or “Canadian Jewish Weekly”) who was a native of Kielce’s neighboring city of Radom. He returned to Poland in the wake of World War II to report on the situation concerning Jewish life there. Ironically, although the article patently conveys the vast degree of destruction wreaked on Jewish life in Kielce and in Poland as a whole, at the same time, there are bursts of optimism in Lipshitz’s piece. In reading his account, one might think that there was a brighter future in store for the Holocaust survivors who had converged on Kielce, just right around the bend. Moreover, there is certainly no blatant tone of an ensuing catastrophe lurking in the shadows. Among the key figures whom Lipshitz highlights with regard to Kielce’s postwar Jewish community, or kehile is Dr. Kahane [Lipshitz refers to him as “Dr. Kahaner”], Chairman of the Kielce Regional Jewish Committee, who operated out of the Committee’s building on Planty Street. Incidentally, this was the very same building in which many of the pogrom victims – Dr. Kahane included – would later lose their lives under extremely violent circumstances. At the time of Lipshitz’s visit, Kahane informed him the following regarding the then current state of Jewish life in Kielce: “There are around 300 Jews in Kielce. Some of them work, others trade/bargain, [and still] others receive help from the Committee. The Committee has a good kitchen where hot meals are served for all those who are in need. There is a kibbutz. We must have help … The situation of the Jews is difficult. From such a large Jewish settlement that there once was in Kielce, there remained only 300 Jews, and not all are Kielcers. Some of the 300 are from the surrounding towns…”  Der Kielcer reporter ["The Kielcer reporter"], published by The Committee for the Resettlement of Kielcer Jews, New York, [vol.] 2-3, June, 1946. (Courtesy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, NYC, RG 1056, Box 2 (of 2).) Der Kielcer reporter ["The Kielcer reporter"], published by The Committee for the Resettlement of Kielcer Jews, New York, [vol.] 2-3, June, 1946. (Courtesy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, NYC, RG 1056, Box 2 (of 2).) And yet, even with this less-than-sanguine image, Lipshitz remarks that Dr. Kahane, who was himself incarcerated during the war in a camp in Lemberg [Lwow], [he] “does not speak with any bitterness. But in his eyes burns the fire of hatred for the barbarians, themselves. A German who falls into Dr. Kahane’s hands will not have a Garden of Eden.” However, the following description of the series of events that unfolded on July 4, 1946 makes plainly clear the tragic reality: that there was no way that Dr. Kahane would ever have any such opportunity to demonstrate the hatred that Lipshitz illustrates in his article: “At about 11 o'clock three lieutenants of the Polish Army entered the room in which Kahane was located at that moment. When the officers came into the room, Dr. Kahane held the telephone receiver in his hand. . . They told him they had come to remove weapons. . . One of them walked up to Dr. Kahane, told him to keep calm because soon everything would be over, and then approached him from behind and shot him straight in the head” (Bozena Szaynok, "The Pogrom of Jews in Kielce, July 4, 1946." Yad Vashem Studies 22 (1992), p. 216).  Sh. Lipshitz’s “A bazukh in Kielce” [“A visit in Kielce”], from which some of my translated excerpts in this blog appear. (Courtesy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, NYC, RG 1056, Box 2 (of 2).) Sh. Lipshitz’s “A bazukh in Kielce” [“A visit in Kielce”], from which some of my translated excerpts in this blog appear. (Courtesy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, NYC, RG 1056, Box 2 (of 2).) In the aftermath of the Kielce pogrom, there was, perhaps not surprisingly, a dramatic increase in the number of Jews emigrating from Poland. Many of those émigrés headed westward, while others eventually made their way to what would soon become the Modern State of Israel. The Kielce pogrom was the final test of survival – the proverbial “last straw.” My grandfather was among the “luckier” ones, since he never even returned to Kielce, following his liberation by the American Forces at the end of World War II. Had he returned, I shudder to think whether I would be here today, writing these very words. Bearing this history in mind, I ask, that come the next yortsayt [Yiddish for “anniversary of a death”] of the Kielce pogrom – the 70th – on July 4, 2016, that you please take a few minutes out of your Independence Day celebrations (if you are American, that is) to remember those, like Dr. Kahane, who died tragically on this day, while trying to protect and defend themselves and their fellow landsmen. I also ask you to please consider the immense value that landsmanshaftn and yizker bikher had and continue to have for those who contributed to them, as well as for future generations. Should you have a yizker bukh or any landsmanshaft material that you would like translated, please do not hesitate to contact me at [email protected].

20 Comments

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed