|

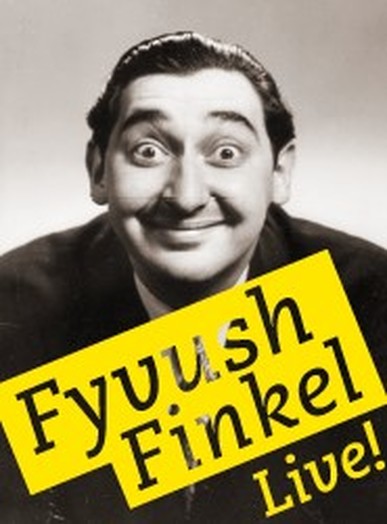

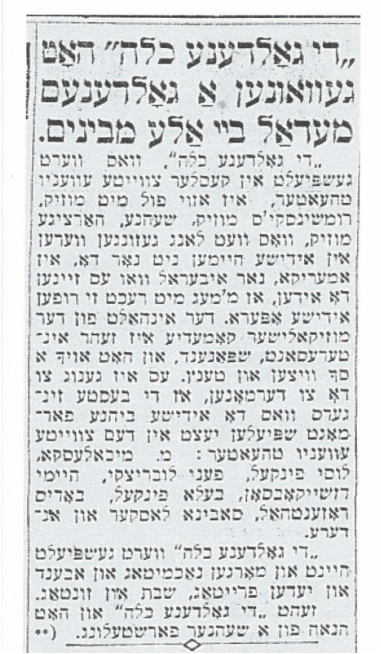

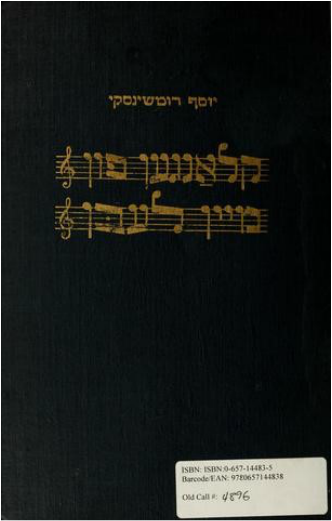

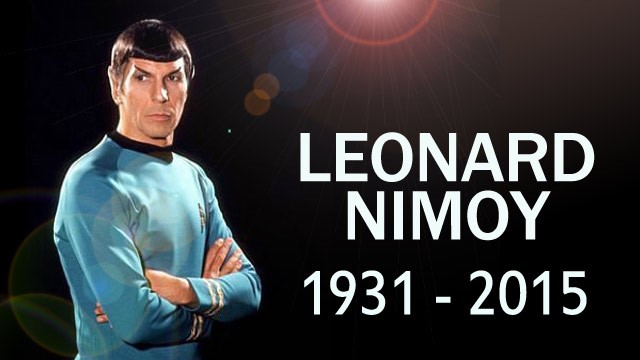

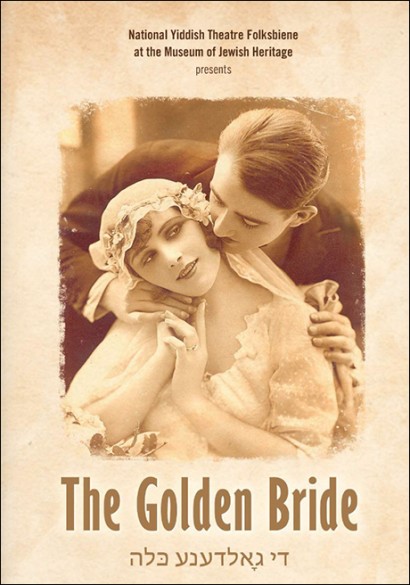

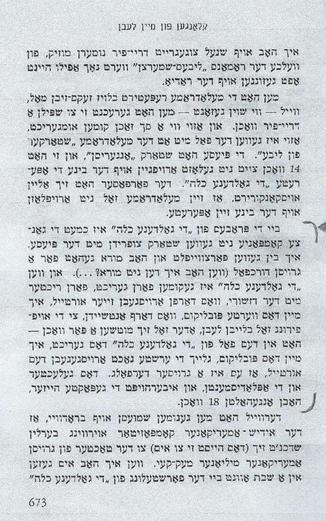

With the recent loss of some of Yiddish theater’s last surviving remnants, I decided that this would be the right time to write about the impact of the Yiddish theater even up until the present (c. 2016). When I speak about this recent loss, I have in mind namely the late Fyvush Finkel (1922-2016), whom I saw perform live at a summer festival only a few years ago in New York City. The relentless performer who began acting on the Yiddish stage in his native New York at the age of 9, ultimately transitioned to the world of American television by the 1990s. He just died at the age of 93 on 14 August 2016.  Fyvush Finkel (1922-2016) in his youth in a theatrical pose. (Courtesy of TheaterMania.com, accessed 8-26-16). Fyvush Finkel (1922-2016) in his youth in a theatrical pose. (Courtesy of TheaterMania.com, accessed 8-26-16). The other name that comes to mind is that of Nina (née Szulman) Rogow (1922-2016) whom I knew personally, as she was a regular and devoted volunteer at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research’s Archives Department, where I worked for several years. Like Fyvush Finkel, Mrs. Rogow was born in 1922. I was sad to learn of her passing in early July. She, too, was a performer in the Yiddish theater, albeit, in Europe. As a native of Minsk and a fluent speaker of Yiddish, she performed with the Belarus State Yiddish Theater in Novosibirsk. After World War II, she and her husband, Yiddish actor, David Rogow (1915-2007), left the Soviet Union and went on to perform in the displaced persons camps of Germany, touring with the Munich Yiddish Theater. Also an actor in Yiddish theater, although most widely recognized for his role as Mr. Spock in the original “Star Trek” television series (1966-1969), was Leonard Nimoy (1931-2015). He passed away in February of 2015. Unlike Fyvush Finkel, who made his acting debut in Yiddish theater, Mr. Nimoy came to Yiddish-speaking roles already as an adult actor living in Los Angeles. Having grown up with Yiddish at home in his native Boston, Nimoy often played juvenile roles when Yiddish theater troupes would visit the West Coast. In that guise, he had the opportunity to perform alongside some of Yiddish theater’s leading stars, including Chaim Tauber (1901-1972) and Maurice Schwartz (1889-1960). According to his own admission, Nimoy always retained a tender place in his heart for the Mame loshn (“mother tongue” – i.e., Yiddish), and as such, was an ardent supporter of the National Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Massachusetts. This brings me to a more upbeat, but related topic and one of the major highlights of my summer. After much ado, I had the opportunity to attend the award-winning Yiddish theater performance, “Di goldene kale” – perhaps better known as “The Golden Bride” – staged by the National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene in New York City from 4 July-28 August 2016. Although the actual performance was conducted entirely in Yiddish (short of a few words here and there in English or in Russian), there were simultaneous supertitles throughout the 2+ hour-long play to help clarify the Yiddish to the mostly non-Yiddish speaking audience. For those in the audience who could follow the nuances of the Yiddish humor, though, this play was all-the-more a splendid treat. A bit more background about “Di goldene kale” / “The Golden Bride”: The music to the operetta or musical comedy was written by Joseph Rumshinsky (1881-1956), considered one of the leading powerhouses of the American Yiddish theater scene of his day, while the lyrics and a libretto were written respectively, by Louis Gilrod (1879-1930) and Frieda Freiman (1892-1962) in the name of her husband, playwright Louis Freiman (1891-1967). The play debuted at David Kessler’s Second Avenue Theatre, in the Jewish Broadway district, on 9 February 1923. According to the English language Forward, it ran for 18 weeks and filled its 2,000 seats before touring the greater United States and international sites, including Buenos Aires, Manchester, England, and Eastern Europe. At the time of its run, on Saturday, 24 February 1923, the Yiddish language Forverts, whose article bore the heading, “`The Golden Bride’ Has Won a Golden Medal Among All of the Mavens” had the following to say about the play: `The Golden Bride,' which is being played at the Kessler Second Avenue Theater, is so full of music, Rumshinsky’s music, beautiful, heart-felt music, which will long be sung in Jewish homes not only here, in America, but everywhere where there are Jews; so one may rightfully call it a Jewish opera. The content of the musical comedy is very interesting, suspenseful, and also has a lot of jokes and dances. It is enough to mention here that the best singers that the Yiddish stage has are now playing at the Second Avenue Theater … See `The Golden Bride' and enjoy a beautiful performance.  Aforementioned article from the Forverts, Saturday, 24 February 1923 (p. 12) entitled, “`The Golden Bride’ Has Won a Golden Medal Among All of the Mavens.” (Digitized article courtesy of Jewish Historical Press, accessed 8-26-16). Aforementioned article from the Forverts, Saturday, 24 February 1923 (p. 12) entitled, “`The Golden Bride’ Has Won a Golden Medal Among All of the Mavens.” (Digitized article courtesy of Jewish Historical Press, accessed 8-26-16). Little did this newspaper article’s columnist realize it back in 1923, but nearly a century later, when “The Golden Bride” would play at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York City during the summer of 2016, the wildly applauding audience would be comprised of far more than only Yiddish speaking Jews. In between its debut and contemporary-day performances, the only other time the play was staged was in 1948. Unfortunately, from that point forward until now, it did not see the light of day. Its revival was greatly due to the efforts of musicologist Michael Ochs, who rediscovered the play’s libretto and lyrics and reconstructed the entire work. Also aiding him in this process were the late Chana Mlotek (1922-2013), my former colleague at the YIVO Institute, and her son, Zalmen Mlotek, artistic director of the Folksbiene. I will not give away the entire plot of the play, should any of my readers have the opportunity to see it at some point in the future (I, for one, hope that it returns to the stage again soon, and that it is performed nationally – if not internationally). But suffice it to say that it is part opera – replete with visually stunning scenery and costumes; melodrama in the “schmaltz” style of the early 20th century; and romantic comedy – part socio-economic commentary. The plot itself opens in a quintessential unnamed shtetl in the land of “Mother Russia,” and ultimately winds its way westward to New York City, America – the land of “Uncle Sam.” The story centers on the fate of protagonist Goldele – Yiddish for “Goldie” – from which the play evidently draws its title. Goldele is a lovely orphan who hails from an impoverished background, but falls into the proverbial shmaltsgrub (i.e., Yiddish for “pit of chicken fat,” but loosely translated to connote, “strike it rich”), when she suddenly receives a large family inheritance. This unexpected windfall prompts Goldele to set out to claim her inheritance in America, while also seeking out her long lost mother, and finding a worthy suitor in the process. Given its high success rate both in 1923 and in 2016 – 93 years later! – as a recipient of the New York Times and New Yorker Critic’s Pick and a two time Drama Desk Award nominee – it is hard to imagine that Joseph Rumshinsky initially feared that his operetta might turn out to be an utter disaster. According to his autobiography, Klangen fun mayn lebn (i.e., Yiddish for “Sounds from/of my life”) (1944), during the rehearsals for “The Golden Bride,” nearly the entire acting company was unhappy with the play.  Front cover of Joseph Rumshinsky’s "Klangen fun mayn lebn" (“Sounds from/of my life”) (1944). (Courtesy of the National Yiddish Book Center, accessed 8-26-16.) Front cover of Joseph Rumshinsky’s "Klangen fun mayn lebn" (“Sounds from/of my life”) (1944). (Courtesy of the National Yiddish Book Center, accessed 8-26-16.) Rumshinsky even states on page 673 of his book that “I was desperate and afraid of a huge failure (when then am I not afraid?...).” Yet, he was ultimately thrilled by its overwhelmingly positive reception (as seen in the following): And when `The Golden Bride' came before the court, before the judge and the jury, who had to give their verdict, I mean the esteemed audience, which has to decide whether the performance should continue to exist, or should limp along for a few weeks – in the case of `The Golden Bride,' the court, I mean the audience, immediately on the first night gave its verdict, that it is a huge success. The laughter and the applause, and especially the packed houses, lasted for 18 weeks. But perhaps the greatest litmus test for the play’s popularity and high success rate was the fact that the performance was visited one night in 1923 by two of the music and theater world’s leading figures of the day: composer and songwriter Irving Berlin (1888-1989) and theater and film director Max Reinhardt (1873-1943). On this subject Rumshinsky modestly takes little credit for the production’s triumph, remarking that “… the happiest person that night was the unknown playwright and provincial actor Louis Freiman, whose operetta `The Golden Bride’ was seen by two such major personalities the likes of Irving Berlin and Max Reinhardt” (p. 674). My great hope for the future of Yiddish theater – especially after having read the biographical profiles of the multi-talented personalities mentioned here and having attended the recent production of “Di goldene kale” / “The Golden Bride” – is that it will continue to flourish and proliferate throughout the world. I would like to see more generations of young Yiddish theater enthusiasts exposed to this once widespread form of entertainment – regardless of whether or not they are Jewish or fluent in the Mame loshn. On the other hand, if Yiddish theater should serve as the conduit for the Yiddish language and its associated culture and literature, I am certainly a strong proponent of that. What’s more, I would love to see a revival of other long-since-forgotten plays once featured on the Yiddish stage. Ideally, though, we will not need to wait another long 93 years for the next such Yiddish theater revival.

If you have any materials pertaining to the Yiddish theater – or otherwise, for that matter – that you would like translated, please feel free to contact me at: [email protected].

14 Comments

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed