|

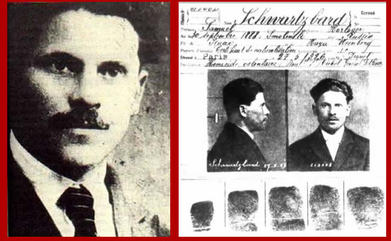

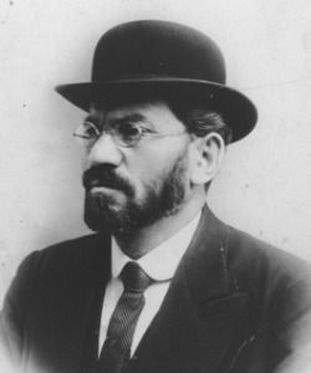

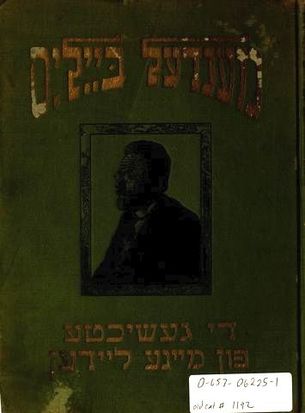

For those of you who are new to my blog or simply did not have a chance to read my previous post: “Wrestling with Identity: What Happens When Old Country Meets New?,” in which I highlighted several of the major themes and subjects that appear in the documents that I have translated over the past nearly 20 years. One of the main themes that I discussed in that blog was the growing divide that I frequently witness between the older generation – the one that is typically more tied to the “Old World” – and the younger generation – usually the one that is more linked to the “New World.” One of the chief forms of that growing divide may be seen vis-à-vis the traditional, religious observance of Judaism, often referred to as “Yidishkeyt” (literally: “Jewishness” in Yiddish). With the shift from one generation to the next, along with the migration from the “Old Country” to the “New Country,” the threads of religious observance oftentimes unraveled – sometimes, in fact, at a rather quickened pace. Due to space constraints, I was previously unable to showcase all of the examples that exemplified the aforementioned pattern of religious and generational divide, which I had in mind for a single blog. As such, I would like to include in the following, the other excerpt I recently translated for a client from the original Yiddish letter that I left out of my January blog. I am certain that this is a theme that is prevalent in the history of many Jewish families that migrated from Eastern and Central Europe to other parts of the world – the United States, South America, and Palestine (later, Israel) – to name a few. Ironically, this divide is also a theme that continues to repeat itself even today, albeit not necessarily in the same form or manner. Translation Follows: p. 2 With God’s help Warsaw, 1939 …. And now, with regard to my child, I believe that I don’t need to praise her. One must have a good husband for her. The world says that for good things, every person is a man [or possibly a husband]. However, that is not the case … Certainly you know, my son-in-law, and you see what it is to conduct oneself Jewishly. Can you take it upon yourself to lead a pure Jewish life, seeing as I don’t believe that my dear daughter will be able to bear it any other way than what she witnessed [while growing up] in my home? And given that I see that you certainly want her, you love her, this is the first thing [i.e., the matter of utmost concern] that she wants … such that [she] does not want to have any hardship and … one with your leading a Jewish lifestyle. Don’t think that I am such a fanatical person or from such a fanatical family. One can see that from my children and from my sister. But still, the first thing [i.e., highest priority] is a Jewish lifestyle. I have a great deal to write about that, but I believe that you understand what I mean. That having been said, write me whether you can undertake this. At that time, I will agree.  “In Commemoration: 1925,” cover of booklet of postcards in Hebrew and Yiddish commemorating the building of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, which the daughter of this letter's author attended in then-Palestine (Warsaw: Jewish National Fund, 1925). (Courtesy of Kedem Auction: https://goo.gl/JfRNfX, accessed 2-7-17.) “In Commemoration: 1925,” cover of booklet of postcards in Hebrew and Yiddish commemorating the building of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, which the daughter of this letter's author attended in then-Palestine (Warsaw: Jewish National Fund, 1925). (Courtesy of Kedem Auction: https://goo.gl/JfRNfX, accessed 2-7-17.) The above translated excerpt was written by a father in Warsaw, Poland on the brink of World War II, to his future son-in-law in Palestine (also frequently referred to as “Eretz Yisrael”). The father is essentially writing here to his potential son-in-law that he will only grant him his blessing to marry his daughter if the young man is prepared to live a traditional Jewish lifestyle – one that his daughter grew up observing in his household. It is also clear from the translated excerpt that if the potential son-in-law were to respond negatively to the author’s demand, he would not be given a blessing to marry the letter writer’s daughter. As evidenced by other letters written by the same author to the identical son-in-law-to-be, the author wanted the young man to quit his current job and get another one that would allow him to observe the Jewish Sabbath by not requiring him to work then. According to my client, the author’s daughter (my client’s mother) and future husband (my client’s father) came from vastly different backgrounds, though they were both born and raised in Poland. She hailed from an upper-middle class Warsaw family that was religiously observant and was herself well-educated. Conversely, her young man came from a non-religious working class family from Pabianice, a town in the vicinity of Łódź. His education ended by the age of 14, at which time he went to work. He became a hairdresser, often servicing clients who were not Jewish. In contrast, she was accepted to study at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, which in part, prompted her to move to Palestine in 1936. As a postscript, my client informed me that her parents – in spite of whatever differences they may have had – married on June 4, 1939 – within close proximity of when this letter was written. Theirs, according to my client, was a happy union that lasted nearly 50 years. As my client expressed to me, her mother always remained a little bit more religious than her father. But this did not adversely affect their many years together. Aside from the themes about which I have now written, I imagine my readers would also like to know something about the characters who appear in the family letters and other documents that I encounter in my translation work. Not surprisingly, the vast majority of the texts I read pertain to common “everyday” Jews in countries such as Poland (the largest number hail from there), present-day’s Ukraine and Belarus, Romania, Slovakia, Czech Republic, Russia, England, South America, South Africa, Palestine and Israel, and the United States. The characters who are given life – indeed, resurrected and immortalized – through their own words, are frequently businessmen such as the above example, written in Warsaw on the verge of World War II. In numerous other cases, the author is a woman – often a mother writing to one or more of her children – as seen in the example portrayed in my previous blog, written in 1920s’ Kraków. Siblings, grandparents, and other close family members are also included in this lineup of correspondents. However, over the years, I have also occasionally found references to well-known historical figures of various bents: writers, politicians, explorers, victims, heroes, and villains. Some of these individuals are still remembered today, even though they may have lived more than a century ago. It is about a few of these figures that I will now elaborate. 1) Roald Amundsen (1872-1928) – This sturdily-built Norwegian explorer who called himself “the last of the Vikings” was the first person to reach the South Pole on December 14, 1911, which he named Polheim – Norwegian for “Pole Home.” Initially, his country, the rest of the world, and even his own crew, thought that Amundsen’s intended goal was the North Pole. His crew only learned of the true target site when their ship was well off the coast of Morocco and Amundsen announced that they were not headed for the North Pole, but to the South Pole. Amundsen and his crew returned to their base camp some 99 days and 1,860 miles after their departure. Amundsen also achieved other great feats, including successfully sailing through the Northwest Passage in 1903 and flying over the North Pole in 1926. He was ultimately killed while flying on a rescue mission in 1928 over the Arctic Ocean. Ironically, only that same year, he was quoted by a journalist as saying the following about his beloved Arctic: "If only you knew how splendid it is up there, that's where I want to die." No offense to the Norwegians (and perhaps Americans of Norwegian stock), but in all honesty, I wonder how many people today even recall this modern-day Viking. When encountering this name in one of my family letters, I was subtly reminded of one of our local Chicago high schools – “Amundsen High” – about which I had heard while growing up there. But even so, I, too, needed to refresh my memory by reading up on Amundsen. Here is a snippet of the reference to Amundsen that I translated from the original Yiddish in an undated letter written in a reprimanding tone by one brother in Europe to another brother, “Yisroel,” in America: “…. Finally, after such a long [period] of silence, you once again remembered and took a little time, and wrote your brothers a letter. As I see it, in America, it is very hard work to write a letter. One must wait for a letter for a good couple of months. Just like Amundsen, who focuses his speech on the North Pole. Certainly, you know who Amundsen is.” Based on the above excerpt, it is evident that in his day – the early 20th century – Amundsen was clearly a celebrated figure on both sides of the Atlantic. Similarly, this correspondence also reflects the misinformation that the world had up until the time that Amundsen’s voyage was already underway, regarding the North Pole being his goal. Perhaps it is also worth mentioning that Amundsen is among the very few famous Gentiles I have encountered in my readings and translations over the past nearly 20 years. I suppose that that in itself speaks loudly for this man’s monumental – albeit unfortunately, little remembered – achievements.  Undated photo of Symon Petliura (1879-1926) (courtesy of Wikipedia: https://goo.gl/jf7Xme, accessed 2-3-17). Undated photo of Symon Petliura (1879-1926) (courtesy of Wikipedia: https://goo.gl/jf7Xme, accessed 2-3-17). 2) Symon Petliura (1879-1926) – Unlike Amundsen, Petliura established a highly negative reputation for himself among Jews, Poles, Bolsheviks, and other political and ethnic groups. It is Petliura, General Secretary of Military Affairs of the Ukrainian People's Army – or at the least, his military forces – who is credited for instigating many of the anti-Jewish pogroms that accompanied the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the ensuing Russian Civil War. According to death counts at the time, “it was estimated that at least 30,000 Jewish men, women and children were massacred in Ukrainian towns by Petlura’s forces” (Jewish Telegraphic Agency, May 27, 1926, accessed 2-2-17). Ultimately, Petliura was assassinated by a Jewish anarchist and Yiddish poet named Sholom Schwartzbard (1886-1938) on May 25, 1926, while strolling in Paris. Schwartzbard purportedly committed this act to avenge the murders of all his close family members during the pogroms of 1919-1920. Schwartzbard was acquitted by a Parisian court, and the murder trial – a cause célèbre of its day – emerged as a political case against the Ukrainian government. Today, Petliura is honored and remembered by the Ukrainian people as a national martyr and hero – one of their leading modern-day freedom fighters. As for Schwartzbard, he was aided by Jews the world over for what many of them considered an act of true heroism and justice. A committee was even formed for this very purpose in Chicago, aptly named the “Sholem Shvartsbard komitet” (or “Sholom Schwartzbard Arrangement Committee”). Indeed, it was this same committee that published Schwartzbard’s two autobiographical works in Yiddish: In krig mit zikh aleyn (“At War with Myself”) (1933) and In’m loyf fun yorn (“Over the Years”) (1934). This controversial, so-called modern-day avenger of justice for Jews, died on March 3, 1938 in Cape Town, South Africa while on a trip to raise funds for the publication of a Yiddish encyclopedia. As per his will, he was later reinterred in Israel. The Shalom Schwarzbard Papers, 1917-1938, may be accessed today at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York City.  Images and police paperwork of Sholom Schwartzbard (1886-1938) at the time of his assassination of Symon Petliura, Paris, France, 1926 (courtesy of Russia House News: https://goo.gl/ld6Wp5, accessed 2-7-117). Images and police paperwork of Sholom Schwartzbard (1886-1938) at the time of his assassination of Symon Petliura, Paris, France, 1926 (courtesy of Russia House News: https://goo.gl/ld6Wp5, accessed 2-7-117). The following is but a brief excerpt regarding Petliura’s pogromist bands, which I translated from Sefer Burshtin (“The Book of Bursztyn”), the memorial book of a town that is located today (c. 2017) in the Ukraine: During the years 1917-18, at the end of the First World War, fights continued for a long time between the Ukrainians, Poles, and Bolsheviks in the Bursztyn area. Because of its strategic placement, Bursztyn sustained a key position. It is clear that the scapegoat was always the Jewish population. Everybody tore pieces from them. Whichever army went through there robbed and raped Jewish women, filling the town with wailing. The women were raped in the presence of their husbands, parents, and children. The most heavily felt in the town were the Petliura-ists. Jewish life was utterly abandoned. In the pogroms and rapes there was participation both by the Ukrainian peasants and the intelligentsia, who demonstrated the lowest degree of animalism and sadism (pp. 147-148).  Mendel Beilis (b. Russian Empire, 1874-d. United States, 1934) (courtesy of the Forward, Dec. 18, 2013: https://goo.gl/lDT1iY, accessed 2-3-17). Mendel Beilis (b. Russian Empire, 1874-d. United States, 1934) (courtesy of the Forward, Dec. 18, 2013: https://goo.gl/lDT1iY, accessed 2-3-17). 3) Mendel Beilis (1874-1934) – A contemporary of the aforementioned noteworthy figures, Beilis is yet another name that has crept into the texts that I have translated. Without going into the elaborate details about him or his trial, suffice it to say that he was at the center of yet another cause célèbre, like Sholom Schwartzbard. However, in Beilis’ case, he was unquestionably a martyr, wrongfully accused of murdering a 12-year-old Andrei Iushchinskii in Kiev. The claim at the time by anti-Semitic hordes, members of the then Czarist government, and other members of Russian society, was that this was a typical case of blood libel that Beilis had perpetrated against an innocent Christian youth. Short of revisionists and anti-Semites, I would contend that there has been unanimous agreement among scholars, journalists, and laypersons in the West, that Beilis was scapegoated for an act he never committed. The reason being, was because he happened to live and work close to where the murdered boy was found. Moreover, Beilis was the only known Jew in the vicinity. This was the key point of significance, given the highly anti-Semitic regime and atmosphere that existed at the time in Czarist Russia. Beilis was arrested shortly after the victim’s body was discovered, and he languished in a squalid prison cell for over two years. His court case – by all accounts a kangaroo trial – took place in Kiev and lasted from September 25 through October 28, 1913. Thankfully, Beilis was finally acquitted of the crime, though the so-called Jewish institution of blood libel was not deemed to be fallacious. At the time, Beilis’ fate was documented in numerous newspaper articles and featured in many postcards. The international Yiddish press was certainly included among those periodicals and ephemera. In the aftermath of the acquittal, Beilis and his family tried to settle in Palestine, but ultimately immigrated to the United States. There, he wrote a memoir about his experiences in 1925, entitled (in Yiddish), Di geshikhte fun mayne layden (“The Story of My Sufferings”). The royalties of the book – which was also translated into English – helped sustain Beilis and his large family financially during his final years. Beilis died unexpectedly in Saratoga Springs, New York on July 7, 1934 and was buried in the same cemetery in Queens, New York, as the renowned Yiddish writer, Sholem Aleichem (1859-1916).  Di geshikhte fun mayne layden (“The Story of My Sufferings”) (1925) by Mendel Beilis (courtesy of the National Yiddish Book Center: https://goo.gl/HyvbHS, accessed 2-3-17). Di geshikhte fun mayne layden (“The Story of My Sufferings”) (1925) by Mendel Beilis (courtesy of the National Yiddish Book Center: https://goo.gl/HyvbHS, accessed 2-3-17). The following is a terse, but highly revealing excerpt from a family letter I recently translated from the Yiddish. The author’s words patently convey that emotions ran high – particularly among Eastern European Jews – during Beilis’ trial. Up until his acquittal, there was always the much warranted fear that Beilis would be found guilty and made to suffer the consequences of such a conviction. Written by Dawid Srebnagóra, in Płońsk, Russian Empire only one day before Beilis was found innocent – to various family members: Płońsk October 27, 1913 p. 3 When I returned home from Płock, I became seriously ill. I made use of doctors and medications. I had recited blessings for Beilis’ procurator. I am now taking a pen in my hand for the [very] first time, and my hand is still shaking. When I read the above words, I initially did a “double take” on the surname mentioned here, and then set out to confirm that this was indeed a reference to Mendel Beilis. I was somewhat stunned (though my hands were not quite shaking) to learn that this letter was written only a matter of hours before Beilis’ long-awaited acquittal and freedom. These are only a smattering of the larger body of famous and not-so-famous names I have encountered in the texts that I have read and translated over the years. Some of the other names that I will mention only in passing, are: Golda Meir (1898-1978), Israel’s first and only female Prime Minister to-date; and the Bielski Brigade, a network of Jewish partisans led by members of the Bielski family of Nowogródek, Poland, from 1942 to 1944 in Western Belarus. They singlehandedly succeeded in rescuing more than 1,200 Jews from an almost certain death. The Bielski Brigade entered the public sphere only as recently as 2009, in the film, Defiance, based on Nechama Tec’s book, Defiance: The Bielski Partisans (1993). I look forward to the diverse and many-faceted personalities I will surely encounter in my future translation assignments. Furthermore, I hope to have the opportunity to share those additional Yiddish translator’s discoveries with you, my readers. Should you have any documents pertaining to famous or not-so-famous individuals, or any other materials that you would like translated from the Yiddish, please do not hesitate to contact me at: [email protected].

19 Comments

Lynne Howell

2/19/2017 09:14:55 am

Absolutely mind-boggling your passion and expertise. The blog stories are amazing; incredibly relevant given current events and how attitudes matter. Thank you.

Reply

2/19/2017 09:26:13 am

Thank you very much, Lynne, for appreciating the time and effort that went into this blog (and all of my blogs). I am glad if I was able to teach you something new about history (Jewish and general) and Yiddish. That was precisely my goal!

Reply

Antonio Celso Ribeiro

2/19/2017 12:07:58 pm

Your blog is awesome, Rivka. Keep doing this wonderful job.

Reply

2/19/2017 12:11:32 pm

Antonio,

Reply

Harry Weinberg

2/19/2017 05:57:05 pm

Just curious, does Mendel Beilis have any descendants living in the US? Although I am not surprised that Beilis was on the minds of world-wide Jewry during his trial, I am disappointed that most American Jews today are unaware of his trial or that of Leo Frank. By mentioning the plight of Beilis, you are doing a great service informing others of this horrific blood libel in the closing days of Tsarist Russia. Keep up the good work!

Reply

Rivka Schiller

2/19/2017 07:10:48 pm

Harry,

Reply

Harry Weinberg

2/20/2017 07:12:04 am

Rivka, Many thanks for answering my question. I plan on reading Jay Beilis' book. Harry Weinberg

Abby Hansen

2/19/2017 05:59:39 pm

I am always searching for references to Roald Amundsen as my great-granddaddy was only one of the many who helped in the preparation of these polar expeditions. So I was pleased that Amundsen was referred to in one of the letters you translated. Would you please keep me informed if you come across more references to Amundsen and his polar missions. Thank you. Abby.

Reply

Rivka Schiller

2/19/2017 07:03:53 pm

Thank you very much, Abby, for writing in and sharing your unique connection to Roald Amundsen.

Reply

Sheindle Cohen

2/19/2017 07:21:02 pm

Hi Rivka,

Reply

Rivka Schiller

2/19/2017 07:24:28 pm

Hi Sheindle,

Reply

Sarah Jacobs

2/20/2017 08:00:05 am

My grandparents who escaped from the Ukraine in the aftermath of the First World War always spoke about the butcher Petliura who they said was responsible for murdering some of their relatives.

Reply

Rivka Schiller

2/20/2017 08:18:32 am

Hi Sarah,

Reply

2/20/2017 10:34:46 am

I know very well who Amundsen was. I've always been fascinated with explorers who went to the world's iciest places, be they the North or South Pole, or the highest mountains. I read Roland Huntford's "Scott & Amundsen" a few years ago. The book focuses on why Amundsen made it to the South Pole while Scott, who was arguably better funded and more experienced, didn't. I was very impressed with Amundsen's meticulous preparation of his journey - for example, he studied how the whalers from northern Norway survived for months on their boats without getting scurvy. He observed that they took along jam their wives had made from berries gathered in the woods - he didn't know why it helped (it provides the vitamin C that is sorely lacking in a diet based on sea creatures); so he took along jam as well. He also used sled dogs as they were bred for working in the frigid cold, whereas Scott took along horses that perished miserably. Fascinating book, and I'm tickled that Amundsen came up on your Yiddish blog!

Reply

Rivka Schiller

2/20/2017 11:11:52 am

Annette,

Reply

Ed Berger

2/21/2017 08:21:32 am

Even though there was a movie made about the Bielski Brothers, most Jews in America aren't aware that their partisan group not only fought the Germans but battled against Poles who helped Germans hunt down Jews. Glad you mentioned them in your blog.

Reply

Rivka Schiller

2/21/2017 08:50:11 am

Hi Ed,

Reply

Adrienne Dinter

2/24/2017 07:06:09 am

I really enjoyed this Rifka, thank you so much.

Reply

2/24/2017 07:38:40 am

Hi Adrienne,

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed