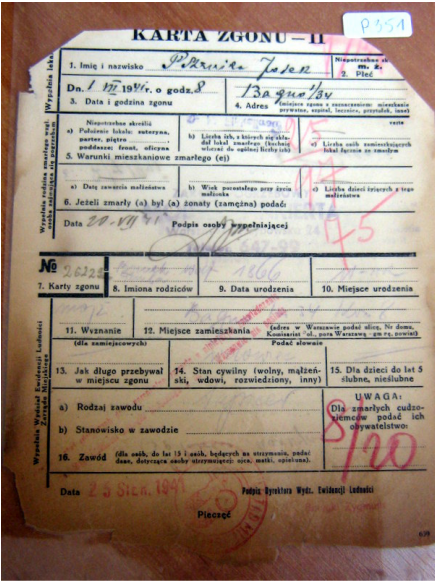

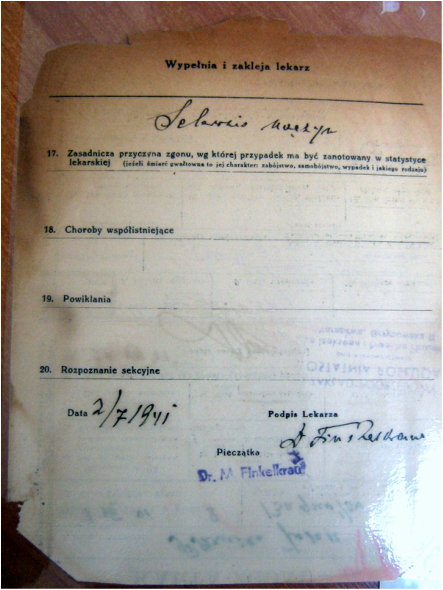

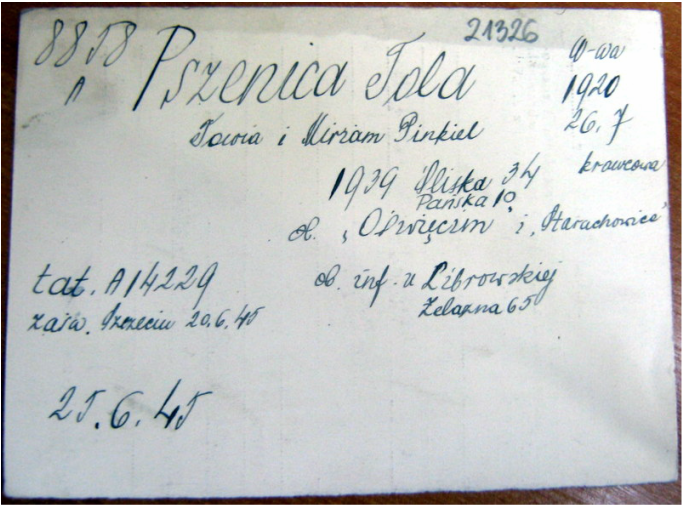

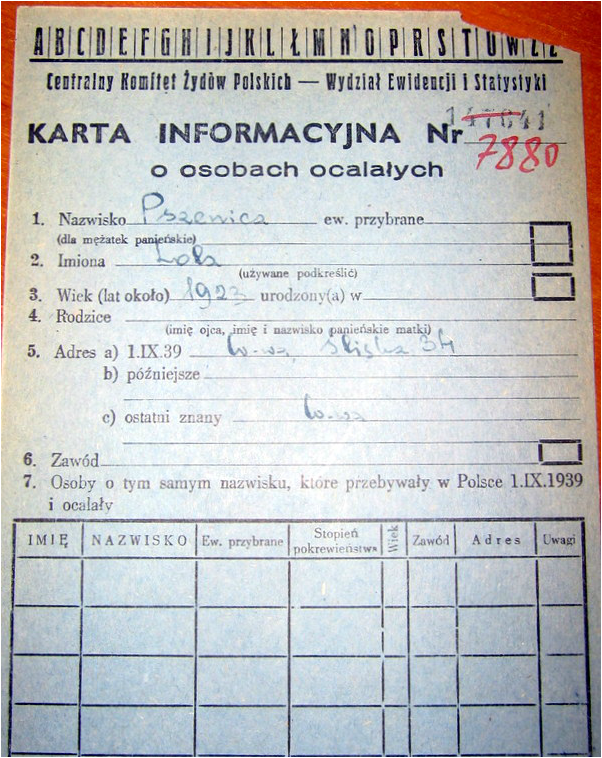

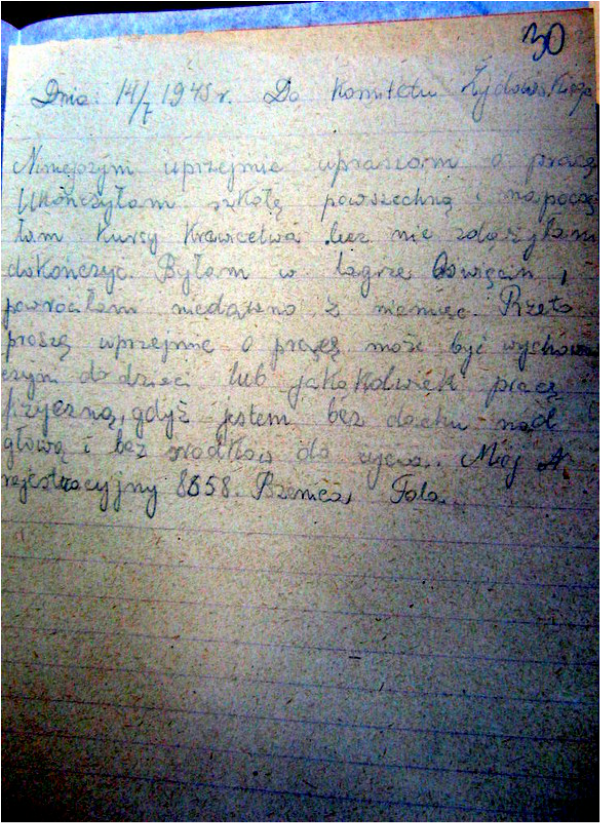

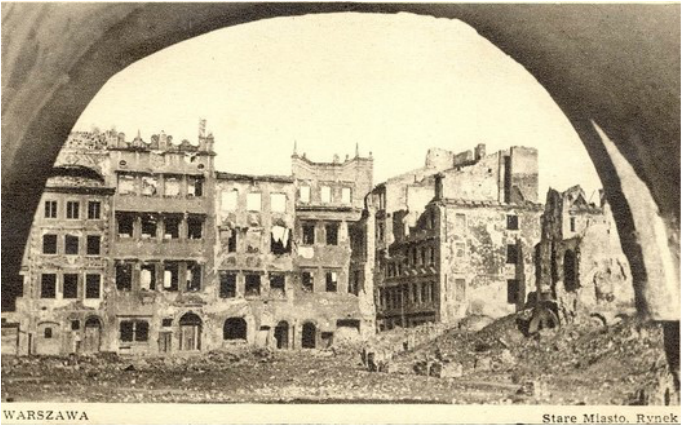

The severed headstone of Yerachmiel Yosef Pszenica before it was restored. The simple text reads in Hebrew: “Here is buried Reb [an honorific term meaning “Mr.” or “Sir”] Yerachmiel Yosef, son of Reb Boruch Zev, died 6 Tammuz 5701” (Wirtualny Cmentarz, accessed 7-14-16). The severed headstone of Yerachmiel Yosef Pszenica before it was restored. The simple text reads in Hebrew: “Here is buried Reb [an honorific term meaning “Mr.” or “Sir”] Yerachmiel Yosef, son of Reb Boruch Zev, died 6 Tammuz 5701” (Wirtualny Cmentarz, accessed 7-14-16). Since I began writing this blog over a year ago, I have definitely seen an increase in the number of readers interested in genealogical matters. For that reason, I have decided to share some of my recent forays into my own family history or genealogy. More specifically, I want to share with you my own experience in Poland nearly two years ago, in September-October 2014, to locate information about my maternal grandparents and their families. I was motivated to write about this particular subject now, after revisiting mementos from the aforementioned trip, and realizing that one of the documents I scanned – a brief, but poignant letter – had been written by hand exactly 71 years ago to the day by my maternal grandmother, in the painful aftermath of World War II and the Holocaust. The coincidental or “bashert” (Yiddish for “destined” or “predestined”) nature of this encounter, especially, prompted me to share my own personal genealogical journey with you in the form of the following blog. Respectively speaking, my maternal grandmother, Tola Pszenica Pinkus (b. 1921-d. 1999) was born and came of age in Warsaw, and my maternal grandfather, Shloime Pinkus (originally Pinkusiewicz) (b. 1904/1905-d. 1998) grew up and was busy raising a family of his own, in pre-World War II Kielce. (This was the city about which I wrote in my blog from this past May.) My grandfather’s mother and my namesake, was named Rywka Gorlicka Pinkusiewicz (b. 1870s-d. 1915/1916), and she, in turn, hailed from the town of Chmielnik, which neighbors on Kielce. (Chmielnik was the town about which I wrote in my blog of a year ago.) The main reason for my journeying to Poland in 2014, my third excursion there since 2002, was the fact that I had uncovered some rather moving information since my last visit there, roughly a decade earlier. This new information that I stumbled upon in c. 2012 came by way of the following incredibly helpful website and database, Wirtualny Cmentarz (Polish for “Virtual Cemetery”), operated by the Foundation for Documentation of Jewish Cemeteries in Poland: The Database of the Jewish Cemeteries in Poland. It was there that I located an entry for my grandmother’s paternal grandfather, Yerachmiel Yosef (also known simply as “Josek” or “Yossel”) Pszenica (b. 1866-d. 1941), who died in the Warsaw Ghetto on the 6th day of Tammuz 5701, or 1 July 1941. Moreover, the headstone – entirely severed from its foundation – included the name of his father, Boruch Zev, which I knew from my late grandmother to have been a prevalent compound name in the Pszenica family. Indeed, my grandmother had both a brother and a paternal uncle who bore these very same names. In addition, I also knew from an earlier visit to Warsaw’s Żydowski Instytut Historyczny (ŻIH), or “Jewish Historical Institute,” that this date of death sounded correct. For at ŻIH I had managed – much to my great amazement – to uncover a death certificate, also from the Warsaw Ghetto, in 1941, issued for my great great grandfather, and signed off on by a Dr. M. Finkelkraut. In light of all these combined pieces of information – coupled with the fact that “Pszenica” (pronounced “Pshe-nee-tsa”) – Polish for “wheat” – is not a common surname, I knew that I had the correct person. What genuinely moved me upon seeing this headstone entry and accompanying photo, was the fact that great great grandfather Pszenica – whom my grandmother had referred to endearingly as “Zayde Yossel,” while she was growing up – had somehow merited having a marked individual grave in a place and time when poverty, disease, starvation, and death were all horribly rampant. Tragically, during the ghetto period, it was more common for the dead to lay in the streets for days before simply being carted off and buried in a mass grave. Clearly, it must have taken the family all of its wherewithal to scrounge up the money to have even this simple headstone carved and engraved as a sign of everlasting honor and devotion to the patriarch of their family. My biggest regret in making this discovery was that neither my grandmother, nor her younger sister, Lola Pszenica Jacobson (b. 1925-d. 2008) was alive to witness what I had found. What’s more, my grandmother had herself most likely never ever seen the headstone, as she had escaped from the Warsaw Ghetto – quite possibly, shortly before her grandfather’s death, also in 1941. Furthermore, she never returned to Warsaw for more than a few days, in the immediate aftermath of the war, for the sole purpose of searching for other possible surviving family members – a search that my grandmother had told me proved to be both utterly heartbreaking, as well as futile. My great aunt Lola, I suspect, must have been present at her grandfather’s burial, as she remained hidden in a bunker beneath the streets of the Warsaw Ghetto throughout the ghetto’s final days (the Warsaw Ghetto uprising – known in Yiddish as “Der Varshever geto oyfshtand”). But she, too, had died too soon for me to share this discovery with her. Sometime after learning of the existence of the headstone and the fact that it was in such a sorry state, as illustrated by the above photo I found on the Wirtualny Cmentarz site, I knew that it was essential that my family have the headstone restored. It was our duty and obligation to see to it that the grave be maintained and cared for, even in our absence. Thus, I arranged with the cemetery caretaker, Przemysław Isroel Szpilman (a relative of Władysław Szpilman, the pianist in the book and film, “The Pianist”) that this take place, which it did, not too long before my visit to Poland. My desire was then to go visit the grave in-person, to see how it appeared in its newly restored state, and to serve as an emissary on the part of other family members who would not be making this trip with me. On some level, I think I wanted to do this most of all, for my grandmother and great aunt, neither of whom was herself any longer among the living. I knew that they would have wanted somebody to see to this, had they still been alive at the time.  Recently restored headstone and burial site of my great great grandfather, Yerachmiel Yosef Pszenica, son of Boruch Zev (d. 6 Tammuz 5701 or 1 July 1941, Warsaw ghetto). (Photograph taken by Rivka Schiller, Warsaw Jewish Cemetery on ul. Okopowa, September 2014.) Recently restored headstone and burial site of my great great grandfather, Yerachmiel Yosef Pszenica, son of Boruch Zev (d. 6 Tammuz 5701 or 1 July 1941, Warsaw ghetto). (Photograph taken by Rivka Schiller, Warsaw Jewish Cemetery on ul. Okopowa, September 2014.) My very first day in Warsaw – I was scarcely off the plane and was terribly jetlagged – one of my friends in Warsaw dropped me off at the Warsaw Jewish Cemetery on ul. Okopowa (Okopowa St.), where I searched for hours in vain for the grave, which I knew from my correspondence with Mr. Szpilman, must be located in some far-flung corner of the cemetery. After two more attempts of searching and hiking through the forest and jungle of the cemetery, on my third visit there, I was fortunate to intercept Mr. Szpilman, who ultimately showed me where the newly restored headstone was. I was adamant that after coming this great distance, there was no way that I was going to leave Poland without actually seeing the grave of my great great grandfather. It is worth noting here that the Warsaw Jewish Cemetery is one of the most vast, sprawling, and overcrowded Jewish cemeteries in the world. As one friend aptly described it to me, it is an entire city, a necropolis, unto itself. Even well before World War II, it was overcrowded. Amazingly, the cemetery managed to survive the widespread destruction wreaked on Warsaw during the Second World War. Indeed, according to Norman Davies in his thorough work, Rising '44: The Battle for Warsaw, 98 percent of Warsaw’s pre-war buildings were destroyed during World War II, particularly, during the Warsaw uprising of 1944. Suffice it to say that this is a small burial site, well concealed within the depths of the overgrown cemetery, not too far from the towering brick wall at the back side of the cemetery. Needless to say, this is not the part of the cemetery that average visitors are ever likely to see. Most visitors will barely venture beyond the more pristine entrance area in which one finds the monument to Janusz Korczak (pen name of Henryk Goldszmit, b. 1878/1870-d. 1942), the martyred Polish-Jewish educator, children’s author, pediatrician, and orphanage director who, rather than choosing the freedom offered him and thereby abandoning his flock of orphans in their greatest hour of need, instead chose to accompany them when they were deported to the Treblinka extermination camp. By this very act, Korczak perhaps knowingly signed his own death warrant. The tidier and less crowded front rows of graves likewise include the shared burial ground of three noteworthy Yiddish writers: Y. L. Peretz (b. 1852-d. 1915), Sh. An-ski (b. 1863-d. 1920), and Yankev Dinezon (1856?-1919). Also in this part of the cemetery is the oft-visited grave of Esther Rokhl Kamińska (b. 1870-d. 1925), the mother of Yiddish theater, as well as of many other noteworthy literary, theatrical, political, and scholarly figures. Having finally found my great great grandfather’s burial site – the main impetus behind this journey – I knew that I also wanted to spend some time at ŻIH, which I had previously visited on my earlier trips to Poland, to see what more I could uncover about my grandmother and her family. What I found there included death certificates – all seriously singed from fires that blazed in the Warsaw Ghetto, especially during the Warsaw Ghetto uprising of 1943, at which time the German Forces, commandeered by SS-Gruppenführer Jürgen Stroop, blew up the Great Synagogue of Warsaw on Tłomackie Street. It is worth mentioning that the Great Synagogue stood next door to the ŻIH building, which remarkably, was not burnt down during the liquidation of the ghetto. It is for that reason alone that I was able to access these family documents these seven decades later.  Pre-World War II postcard depicting the magnificent Great Synagogue on Tłomackie Street (completed in 1878), which neighbored on the Żydowski Instytut Historyczny (ŻIH), to the left. The synagogue was dynamited by SS-Gruppenführer Jürgen Stroop at the close of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, on 16 May 1943. (Courtesy of the Jewish Historical Institute, accessed 7-15-16.)  Death certificate of Josek Pszenica (i.e., Yerachmiel Yosef Pszenica), who died on 1 July 1941 at 8:00 o’clock in Warsaw, Poland and was born in April of 1866 in the same city, making him 75 years old at the time of his death. (Photograph taken by Rivka Schiller, fall 2014; courtesy of the Żydowski Instytut Historyczny (ŻIH), Warsaw, Poland.) Death certificate of Josek Pszenica (i.e., Yerachmiel Yosef Pszenica), who died on 1 July 1941 at 8:00 o’clock in Warsaw, Poland and was born in April of 1866 in the same city, making him 75 years old at the time of his death. (Photograph taken by Rivka Schiller, fall 2014; courtesy of the Żydowski Instytut Historyczny (ŻIH), Warsaw, Poland.) The death certificates were from one of my grandmother’s paternal great aunts, “Raizel Pszenica,” a maternal first cousin named “Moishe Pinkiel,” and from her paternal grandfather, the one about whom I have written here: “Yerachmiel Yosef Pszenica.” The secular date of death on the death certificate: 1 July 1941 was the matching equivalent of the Jewish date of death found on the headstone in the Warsaw Jewish Cemetery: 6 Tammuz 5701, so there was absolutely no question that all of my puzzle pieces concerning Yerachmiel Yosef Pszenica were falling right into place. In addition, I found different registration cards for both my grandmother and her sister, Lola. In the wake of World War II, Poland was still in a state of general chaos, and Jewish survivors were anxious to locate possible surviving relatives. As a result, the Central Committee of Polish Jews (CKŻP), the main and essential political and social organization of the Polish Jewish community at that time, established a network of offices in various parts of the country to assist the returning survivors in locating family and with their most basic needs.  Death certificate of Josek Pszenica (i.e., Yerachmiel Yosef Pszenica), verso, signed by Dr. M. Finkelkraut on 2 July 1941. (Photograph taken by Rivka Schiller, fall 2014; courtesy of the Żydowski Instytut Historyczny (ŻIH), Warsaw, Poland.) Death certificate of Josek Pszenica (i.e., Yerachmiel Yosef Pszenica), verso, signed by Dr. M. Finkelkraut on 2 July 1941. (Photograph taken by Rivka Schiller, fall 2014; courtesy of the Żydowski Instytut Historyczny (ŻIH), Warsaw, Poland.) Among these offices was one in Praga, a neighborhood just beyond Warsaw, east of the Vistula River. According to my grandmother and great aunt, most of Warsaw’s infrastructure was so bombed-out and covered in rubble at that time, that the “Jewish Committee” was simply unable to set up shop in Warsaw proper. The following is but one of many images depicting how utter and widespread Warsaw’s destruction was by the close of World War II, at the time when my grandmother and great aunt returned there to search for living relatives. As I recall my grandmother relating to me, when she and my great aunt returned to what had formerly been their home prior to World War II, a large and regal-looking building at ul. Śliska 34, they found nothing more than a pathetic-looking single wall left standing. The rest of the building had been leveled during the bombings of and street combat fought during the war. As for former building residents, the two Pszenica sisters were unable to find any additional surviving members of their immediate family. The only person whom they encountered was the building’s superintendent, who informed them that no other members of their family had returned, aside from the two of them. While searching yet further in their neighborhood for any sign of surviving family members, my grandmother met a Polish clerk, somebody who had obviously known her father before the war. The clerk remarked to my grandmother what a shame it was that “Pan Pszenica” [“Pan” being a Polish title of honor, something akin to “Mr.” or “Sir”] had not survived, as the greater Warsaw community was now in dire need of his erudite knowledge and multilingual skills in rebuilding their infrastructure. It was only at that time – after her father had already been dead for several years – having died of starvation in the Warsaw Ghetto – that my grandmother ultimately learned of her father’s widely recognized excellent reputation and linguistic skills. According to my grandmother, her father, Towia Gitman Pszenica, was fluent in seven languages.  View of ul. Śliska today (c. 2016), most of which was rebuilt in the wake of World War II. The large cream-colored building in the forefront bears the address: ul. Śliska 51 and was formerly the Bersohn and Bauman Children’s Hospital, which both my grandmother and great aunt recalled from their prewar childhoods. The structure was erected thanks to funding from two wealthy, philanthropic Jewish families in the late 1870s to treat Warsaw’s Jewish children. The building somehow withstood the Second World War and today houses the Children of Warsaw Hospital. (Courtesy of Robert Gujski's "In Art" Gallery - Warsaw, accessed 7-16-16.) One of my grandmother’s registration cards, which I have included here, attests to the fact that she was incarcerated in Auschwitz and Starachowice, a labor camp. It also provides the tattooed identification number issued to her by the Germans in Auschwitz-Birkenau: A-14229. This was the number that I was accustomed to seeing on the arm of my grandmother from the time I was a little girl, and which I later found – some years after her death – in the book, Żydzi Polscy w KL Auschwitz Wykazy Imienne / Polish Jews in KL Auschwitz Name Lists (2004), published by none other than ŻIH. Additionally, the registration card mentions the names of my grandmother’s parents: Towia (Gitman) and Miriam Pinkiel Pszenica, as well as the address at which she lived in Warsaw at the outbreak of World War II: ul. Śliska 34. All of these details were merely further confirmation of information I had learned years before, directly from my grandmother herself. But of all the documents I unearthed at ŻIH, perhaps the most emotionally stirring one of them all was that of the short letter my grandmother composed by hand in pencil in what, as I have been informed by native Polish speakers, is a very nice and grammatically correct Polish. This letter, which is quite well preserved – but also rather faint and difficult to make out today on account of the pencil used and the acidification of the paper – was written exactly 71 years ago to the day on which I am composing these very lines: 14 July 1945.  Registration card of Tola Pszenica filled out on 25 June 1945 under the auspices of the Central Committee of Polish Jews in the vicinity of Warsaw, shortly after the end of World War II. Among the various information provided here are the names of some of the concentration and labor camps in which my grandmother was incarcerated (i.e., Auschwitz, Starachowice); the number she had tattooed on her arm at Auschwitz-Birkenau (A-14229); that she was the daughter of Towia (Gitman) and Miriam Pinkiel Pszenica and had resided in Warsaw at ul. Śliska 34 in 1939, prior to the outbreak of World War II; that she was born on 26 July 1920 (incorrect; she was actually born in 1921); and that she had training as a seamstress. (Photograph taken by Rivka Schiller, fall 2014; courtesy of the Żydowski Instytut Historyczny (ŻIH), Warsaw, Poland.)  Registration card issued by the Central Jewish Committee of Polish Jews to Lola Pszenica, the younger sister of my grandmother, Tola; and to other survivors of World War II and the Holocaust. The above form states that my great aunt was born in 1923 (incorrect; she was born in 1925) and that she resided in Warsaw at ul. Śliska 34 as of 1 September 1939, the day on which Germany declared war on Poland. (Photograph taken by Rivka Schiller, fall 2014; courtesy of the Żydowski Instytut Historyczny (ŻIH), Warsaw, Poland.) In this letter, which is addressed to the “Jewish Committee,” my grandmother makes a heartfelt plea, stating that she is now looking for some means of work; that she had training as a seamstress (my grandmother was always remarkably talented when it came to crocheting and knitting); that she was in the Auschwitz Concentration Camp; and that, in her own words: “… jestem bez dachu nad głową i bez środków do życia.” (“… I am without a roof over my head and am destitute.”)  Letter written in Polish by Tola Pszenica on 14 July 1945 in which she presents her case before the “Jewish Committee,” and requests some sort of job, as she is now destitute and without a roof over her head. She mentions that she received some training as a seamstress and that she was in the Auschwitz Concentration Camp. Shortly after writing this letter, my grandmother was hired to work in the children’s home in Otwock, overseen by the Jewish Committee, not far from Warsaw. My grandmother worked there for several months until she left Poland for Germany, sometime before the Kielce pogrom of 4 July 1946. (Photograph taken by Rivka Schiller, fall 2014; courtesy of the Żydowski Instytut Historyczny (ŻIH), Warsaw, Poland.) Reading that familiar handwriting of my grandmother, yet in another language in which I do not recall ever seeing her actually compose anything on paper – I could hear the desperation and fear in her words. Yet, at the same time, I could still sense my grandmother’s inner strength, her readiness to take control of a horrible situation, and her preparedness to fend for herself. These were all traits that I knew to be representative of my grandmother, a woman who had an incredibly strong spirit and who somehow managed to elude death numerous times in her life, before tragically succumbing to cancer at the age of 77. I remember the final days leading up to her death, for example, when my grandmother was in extreme physical pain due to the effects of chemotherapy and the cancer that was rapidly metastasizing inside of her. Nonetheless, she somehow got up the physical strength to make her widely popular apple cake – a time consuming and physically arduous job for anyone, let alone for somebody who was now bedridden much of the time. She was determined that she complete this task for my younger brother, David, who was on a brief visit home from Israel, where he was studying at the time. When my brother returned to Israel, he took the entire cake with him in multiple Gladware containers, which he subsequently shared with his friends there. Everyone had heard about his “Bubbe’s” marvelous apple cake. Sadly, that apple cake outlived my grandmother, who died only a couple of days after making the delicacy for her grandson. My brother arrived in Israel right around the time that my grandmother died, making it impossible for him to return home again in enough time for the funeral and burial. As I recall hearing, he continued to hold onto those last pieces of apple cake even after they were far from edible. I think this was his own way of not letting go of my grandmother too quickly. Since my grandmother’s death those 17 years ago, no family member has been able to successfully replicate that apple cake, whose recipe my grandmother had created and knew by heart, but never recorded on paper. Believe me, we all have tried multiple times. Baking an apple cake for one’s grandson may seem an ordinary task to some. But to those of us who watched her and knew the struggle she was fighting inside her body, it was like the Battle of Waterloo. My grandmother knew she was nearing the end of her life; she could have resigned herself to this. But for her, every second was important, and there were no excuses. As I recall my grandmother relating to me, it was likely not long after she wrote the letter to the Jewish Committee that she was asked to interview for a job working at the children’s home in Otwock, a short distance from Warsaw. The orphanage – like other Jewish-run organizations and institutions that existed in Poland in the wake of World War II – was overseen by the Central Committee of Polish Jews. (I wrote about the orphanage and one of its particular orphans, Walter Saltzberg, in the Forward in August 2011.) But because my grandmother was still quite swollen and ill in the aftermath of the war, due to starvation and wartime injuries, she was unable to go in-person herself to interview for the position. Instead, she sent my great aunt, her sister Lola, in her stead. If I understood correctly, my great aunt actually posed as my grandmother and got my grandmother the job at the orphanage. This kind of stunt would be difficult for most of us to pull off even in good health, but my grandmother knew it was her only chance at survival. Although she did not work there for more than several months, at the most – as I know that she had already left Poland for Germany by the time of the infamous Kielce pogrom of 4 July 1946 – she still had memories of those children years later. According to her, a number of those children had been incarcerated with her in the camps during the war. These were the major tasks that I had set out for myself to accomplish in Warsaw – to find great great grandfather Pszenica’s grave and any documentation about my grandmother’s family. Obviously, I could not resurrect my grandmother, great aunt, or all the ghosts of their murdered family members through achieving these tasks. Nevertheless, I felt that at the very least – and perhaps, in fact, at the very most – I had helped to memorialize these individuals – to give some lasting identity to those who have virtually nothing tangible today to attest to their sheer existence. After all, at the end of the day what is it that truly remains of a person, but the memories, the deeds, and the name of that person?

The aforementioned account of my search for information about my maternal family in Poland, which both began and ended in Warsaw, is but a part of the genealogical journey I made in the fall of 2014. The remainder of that two-week long trip also included excursions to Kielce and Chmielnik, where I explored the respective city and town of my maternal grandfather and great grandmother; Kraków; Majdanek, where my great aunt Lola was incarcerated following the destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto and her subsequent round-up at Umschlagplatz in May 1943; and Treblinka, where much of my family and Polish Jewry, as a whole, was brutally murdered. However, given the space constraints of this blog, I will conclude here and leave the rest for a future blog. Trekking back to Poland and following the threads of my grandmother’s story was both difficult and moving for me. But, it was also comforting. I take solace in the fact that, in this small way, I am telling the story that my grandmother and her family can no longer tell themselves… and that, through this, their legacy lives on. If you have any old or newly uncovered documents pertaining to your own family history that you would like translated, please feel free to contact me at: [email protected].

35 Comments

Tom

8/7/2016 08:48:56 am

As you said the "story was both difficult and moving" - having the ability to flesh out your family's past with detailed knowledge is amazing and finding those documents are, well, lucky to say the least. Thanks for a glimpse into a past I'll probably never find for my own family, but appreciate for yours.

Reply

Efrat

11/17/2019 12:31:20 am

Hi Tom

Reply

8/7/2016 09:55:29 am

Thank you very much, Tom, for your thoughtful and generous words. Admittedly, when I began this research into my family actually years ago, I never would have imagined that I would find anything -- certainly not what I ended up uncovering.

Reply

8/8/2016 06:22:35 am

How wonderful that you had your great great grandfather's gravestone restored and went back to visit it, and to also find other documents about your grandmother's family. I totally empathize with journeys like that to put the pieces of the past together and give these ancestors some dignity. Thanks also for the images you shared, especially of post-war and present-day Warsaw, and of that amazing Jewish cemetery!

Reply

8/8/2016 08:45:26 am

Rivka, I shared your blog so that more people can know about the wonderful things you are doing.

Reply

8/8/2016 09:35:53 am

Judy, 8/8/2016 08:56:57 am

Thank you very much, Annette, for your thoughtful sentiments. I know that you, too, have made your own genealogical journey back to visit your ancestral home in Germany. As such, I'm sure that what I have described in my blog must resonate with you on a deep level.

Reply

8/8/2016 08:33:25 am

I actually wanted to compliment you on your blog. It is all so interesting to me.

Reply

8/8/2016 09:41:10 am

Dear Dr. Wasserman,

Reply

8/8/2016 09:52:44 am

Dear Arthur (Avrom),

Reply

8/8/2016 08:37:32 am

I have recently signed up for the above Rivka's Blog which I find most interesting. It contains a wealth of information, especially for those of Polish ancestry.

Reply

8/8/2016 09:49:25 am

Rubin,

Reply

Russ Maurer

8/8/2016 11:46:55 am

Rivka, thank you for sharing these precious and intimate discoveries with all of us. You have done well to have pieced together the evidence to recreate your ancestors so vividly.

Reply

8/8/2016 03:15:43 pm

Russ, thank you so much for your sincere and generous comments regarding my research and discoveries. This means a great deal to me -- especially coming from such an astute genealogist and scholar such as yourself!

Reply

Irena Brubaker

8/8/2016 01:42:30 pm

Thank you for sharing. I am happy to learn you have succeeded in finding & restoring foot prints of your family members' life in Poland. Your Grandmother is proud of you for job well done. The apple cake story moved me to tears...

Reply

8/8/2016 06:28:24 pm

Irena,

Reply

Bozena Brzeczek Masters

8/8/2016 05:56:03 pm

[The following is a post previously received on Facebook and re-posted here with the permission of Bozena Brzeczek Masters:]

Reply

Rivka Schiller

8/9/2016 07:30:53 pm

Hello Bozena,

Reply

Lisa Sharon Belkin

8/8/2016 06:04:36 pm

You have done an incredible amount of work here! I look forward to reading other materials of yours!

Reply

8/8/2016 06:39:03 pm

Thank you so much for your note of recognition, Lisa!

Reply

Mindy Schiller

8/8/2016 06:43:20 pm

Your post was very special, Rivka. It brought me to tears.

Reply

8/8/2016 07:00:30 pm

Thank you, Mindy, for your thoughtful remarks. Indeed, I think you were correct about the story regarding Bubbe and the apple cake. It did have a place here.

Reply

Eugene Markow

8/9/2016 08:07:30 am

Great, and very detailed, blog post. I especially enjoyed looking at the old pre-WWII postcard and other photos & documents.

Reply

8/9/2016 05:28:02 pm

Thank you very much, Eugene, for your lovely remarks.

Reply

Ruth Baerman

8/9/2016 01:53:11 pm

Rivkaleh (if I may be so bold), this needs to be a book! Just read for 10 minutes, just enough to get my feet wet, so to speak. Brilliant and beautifully written.

Reply

Rivka Schiller

8/9/2016 07:01:49 pm

Ruth,

Reply

Ruth Altman

8/9/2016 04:12:54 pm

A very moving story Rivka. I just returned from a trip to Poland and Lithuania and have been to the places you mentioned here. Thank you.

Reply

Rivka Schiller

8/9/2016 07:08:49 pm

Thank you very much, Ruth, for your kind remarks and for sharing that information about your own recent trip to Poland and Lithuania. I hope you had a pleasant and informative journey.

Reply

Rivka: Enjoyed reading your blog and amazing quest to restore dignity and memories to your relatives. I found your blog from a Face Book post- I am about to launch a Kickstarter campaign for an educational short doc series on the Holocaust, and was just doing some PR research in order to get the word out. I am always fascinated with the past and the realization that once people leave this earth, the preservation of memories and historical events is an important duty for all of us- otherwise all that dies along with humanity. Thanks for sharing your story, and glad you were able to find some answers along with being able to restore your great grandfather's headstone!

Reply

8/14/2016 08:45:46 pm

Phil: Thank you very much for your thoughtful remarks about my blog and recognition of my achievements! I also appreciate your sharing this bit of information about your own work into the preservation of the memory of the Holocaust. I am glad to help you promote your doc series, if I can (perhaps we can discuss this further elsewhere :-)).

Reply

8/18/2016 06:55:00 am

Dear Rivka,

Reply

8/18/2016 10:46:22 am

Dear Lauren,

Reply

1/8/2017 05:32:58 am

I just wanted to congratulate You on your blog. I was glad that You described the story of Dom Sierot and Janusz Korczak. My father Misha Wasserman Wroblewski was the only teacher that survived the deportation on August 5th to Treblinkas gas chambers. I also went to Poland but I found almost nothing or actually nothing new.

Reply

1/9/2017 08:29:04 am

Dear Dr. Wasserman Wroblewski,

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed