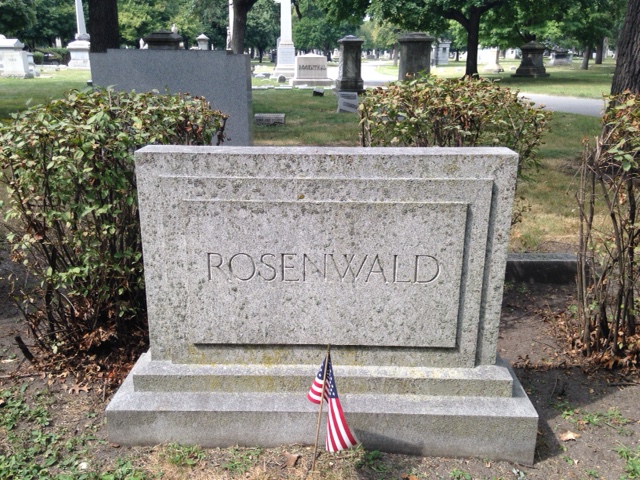

Julius Rosenwald (1862-1932) (https://goo.gl/xIJ2pP) Julius Rosenwald (1862-1932) (https://goo.gl/xIJ2pP) Growing up Jewish in Chicago, as I did, with roots in the city dating back four generations (to 1890) on my paternal side, I felt very much a part of the landscape of the city’s history. More specifically, I felt steeped in the history of the local Jewish community, which was marked by such notable names as Dankmar Adler (architect, 1844-1900), Benny Goodman (musician, 1909-1986), Barney Ross (boxer, 1909-1967), Ben Hecht (journalist, playwright, screenwriter, and novelist, 1894-1964), Meyer Levin (journalist, novelist, and playwright, 1905-1981), Saul Bellow (novelist, 1915-2005), and Julius Rosenwald (department store mogul and philanthropist, 1862-1932). Thus, when Aviva Kempner, an award-winning filmmaker and producer contacted me last spring to ask if I would like to do some research for her on behalf of the latest film she was working on regarding Julius Rosenwald and his philanthropic efforts toward African Americans, I was thoroughly enthralled. The research would involve examining Yiddish press articles from the Teens, Twenties, and Thirties of the Twentieth Century – newspapers that included the Forverts (Yiddish Forward), Morgen zshurnal (Morning Journal), and the Yidishes tageblat (Jewish Daily News) that related the status and treatment of African Americans (at that time, still referred to as “Negroes”) in the American South. What I knew about Rosenwald was that he had been a leading figure in the still-existent Sears, Roebuck & Company department store and mail order enterprise, founded in Chicago by Richard Sears and Alvah Roebuck in 1886; that he had been a trustee at the University of Chicago (my Alma Mater), on whose campus befittingly stands in his memory a Rosenwald Hall; and that he had also provided significant funding to Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry. I also knew, more tangentially, that he had resided in the affluent German-Jewish Chicago enclave of Hyde Park-Kenwood, where President Obama resided prior to becoming President of the United States; that he had been affiliated with the Classical Reform Chicago Sinai Congregation, and that his grandson, Armand Deutsch, had been one of the possible intended victims of Richard Loeb and Nathan Leopold, two infamous members of Hyde Park-Kenwood’s elite German-Jewish community, who subsequently murdered Deutsch’s classmate, 14-year-old Bobby Franks. I had also heard that Rosenwald had done a great deal for African Americans; however, as to what exactly that meant, I had relatively little knowledge. I would not truly learn the full extent of Rosenwald’s philanthropic contributions – particularly to African Americans – until seeing Ms. Kempner’s documentary, Rosenwald, this past summer, in my local theater. As a Jew, Rosenwald was particularly moved by the plight of African Americans, about whom he was noted as stating the following: "The horrors that are due to race prejudice come home to the Jew more forcefully than to others of the white race, on account of the centuries of persecution which they have suffered and still suffer." As an outgrowth of his relationship with Booker T. Washington (1855-1915), one of the foremost African Americans of his day, and the social justice influence of Rabbi Emil G. Hirsch (1851-1923) of Sinai Congregation, Rosenwald embraced the cause of bettering the lives of African Americans – especially those in the rural South. This included providing over four million dollars (equivalent to over seventy-four million dollars in 2015) in matching funds to the construction of 5,300+ schools in the “Jim Crow” southern states. Informally, these schools became known as the “Rosenwald Schools,” and they lasted up until the time of desegregation. Thanks to these schools, over 500,000 students received an education in fifteen states, ranging from Maryland to Texas. The “Rosenwald Fund” – the umbrella fund for the “Rosenwald Schools” – was established in 1917. In addition to helping found the aforementioned schools, it also established a fellowship fund for talented African Americans and white Southerners, which spanned the years 1928-1948, and provided educational opportunities for aspiring writers, artists, and singers, including: Marian Anderson, Ralph Bunche, W. E. B. DuBois, Ralph Ellison, Zora Neale Hurston, James Baldwin, Jacob Lawrence, and Woody Guthrie. As for my research toward the documentary, Rosenwald, it provided background material that demonstrated that even as recently as the 1930s, African Americans were still being treated not only as second class citizens, particularly in the American South, but actually continued to function as outright slaves in various settings, which included southern plantations. Clearly, it was scenes such as the following (extracted and translated from the above Yiddish Forverts article from 1927), which opened Rosenwald’s eyes regarding the mistreatment and persecution of African Americans in the United States, and provided the impetus for much of his philanthropic work: Negro Slavery A few days ago it was reported in the newspapers that in the Mississippi Valley, which became very familiar on account of the great flood, there still exists full-fledged Negro slavery. The Negroes are kept there on the plantations like real slaves. They are sent by force to work, and are considered the property of the plantation owners, just like in the good old days of slavery in America. At that, a characteristic fact is related by a doctor, who was sent to the flooded region to vaccinate against pox, in order to safeguard the flocking populace against an epidemic. The doctor and his aids completely unexpectedly encountered a disturbance in their work with the Negroes. They [the Negroes] were afraid of allowing themselves to be vaccinated against pox without the agreement of their bosses, the plantation owners. They told the doctor to go to the plantation owners to ask for their permission. And how surprised the doctor was, when the plantation owners indeed refused to give their permission. They only agreed later on, when the doctor gave them a warning that he would entirely end his sanitation work in the region. Distressfully, slavery’s stain of shame still continued to rear its ugly head in America – certainly, well up until the time of Rosenwald’s death in 1932 – and indeed, well beyond. I am proud to have participated in the making of this compelling film, and strongly urge those of you who haven’t yet seen it, to make an effort to see it if and when it comes to your local area. Ultimately, I hope that Rosenwald will come to DVD, so that those of you who were unable to see it in the theaters will still have an opportunity to see it on your own viewing screen. For additional information about Julius Rosenwald, his philanthropic efforts, and the documentary film about him, visit: www.rosenwaldfilm.org.

4 Comments

Matt Kaplan

2/7/2016 09:07:54 pm

Hi Rivka;

Reply

2/7/2016 09:21:07 pm

Hi Matt,

Reply

SHARUNDA THORN

5/10/2017 10:43:36 am

Hi my name is Ms.Thorn. I was reading the passage and I wanted to inform you there is a school left in Jacksonville Texas (east Texas)that we are currently trying to restore. This building is a historical land mark. Our mission for the Rosenwald School in the community is to create an environment that achieves equality for the people and ensure that each woman, man, and child is fully respected and learn to respect others. To provide a safe and caring place for growth for the future. we are looking for donations, ideals or even help to restore the history. There is a go fund me page set up under the Rosewald school new beginning anything helps even a prayer. Thank you for reading and may God Bless, for more information I can be emailed at email above.([email protected]) Thank you

Reply

5/10/2017 11:57:18 am

Dear Ms. Thorn,

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed