|

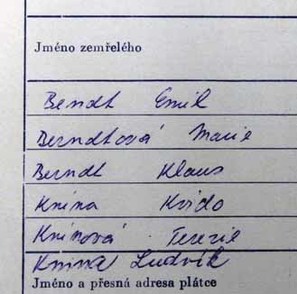

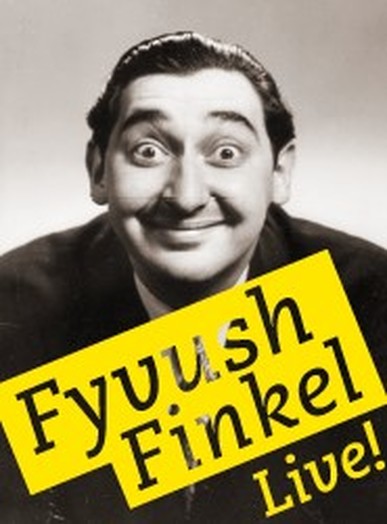

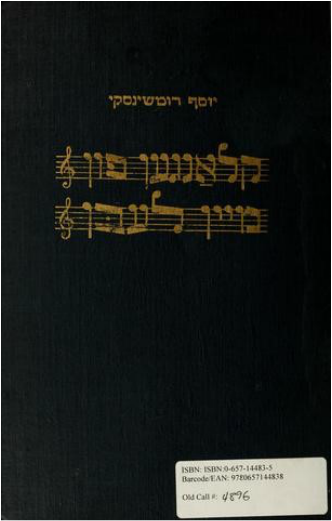

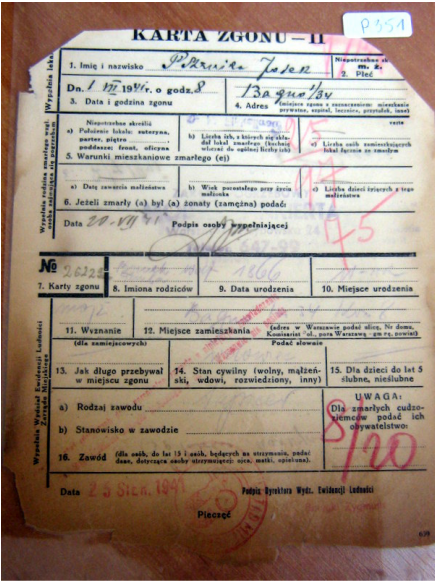

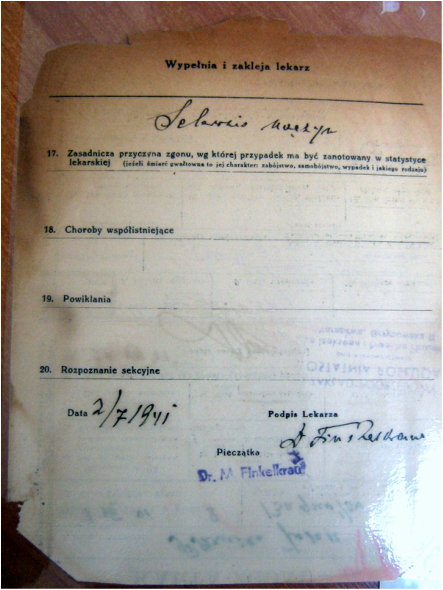

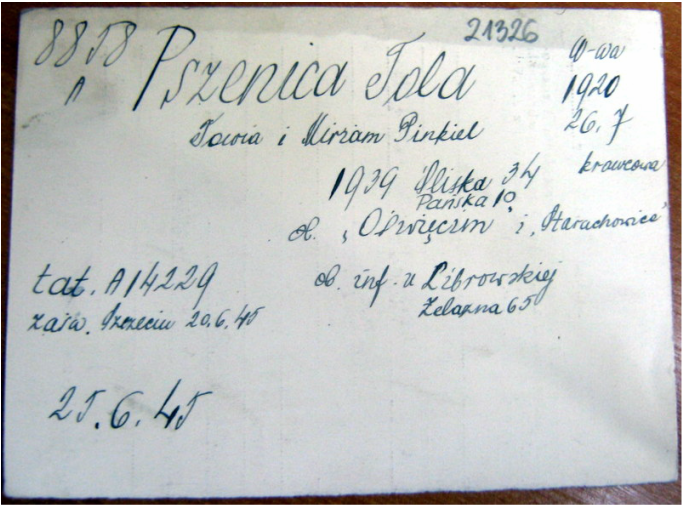

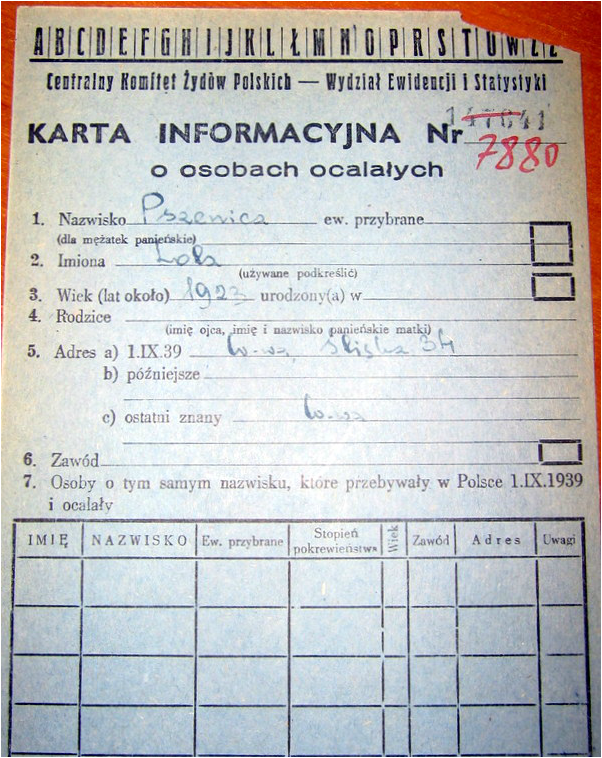

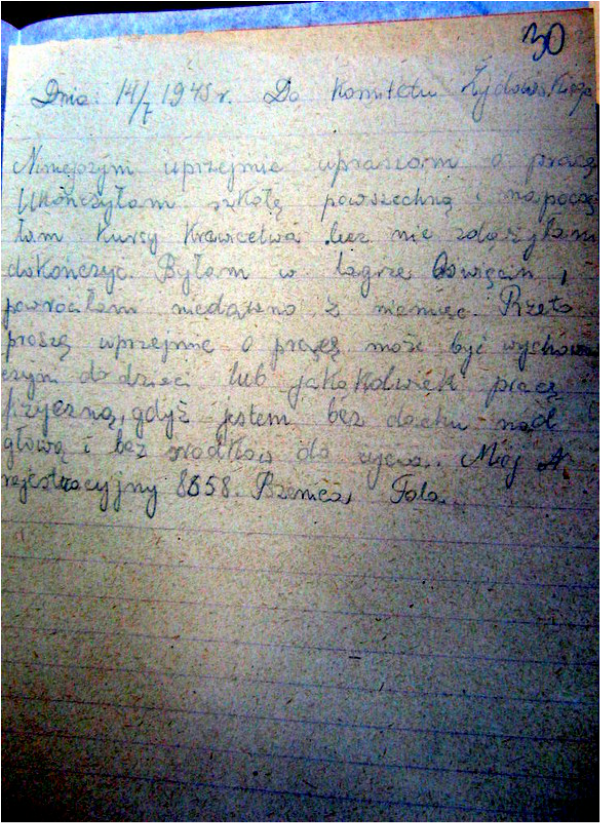

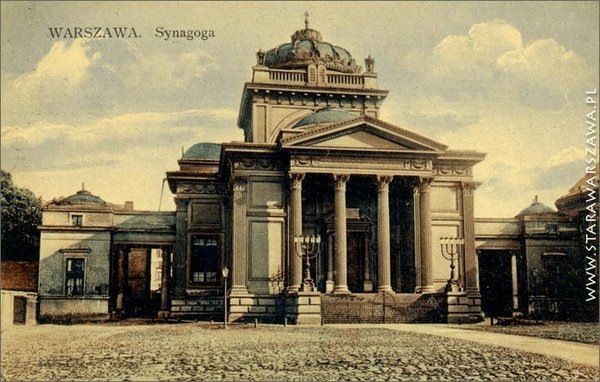

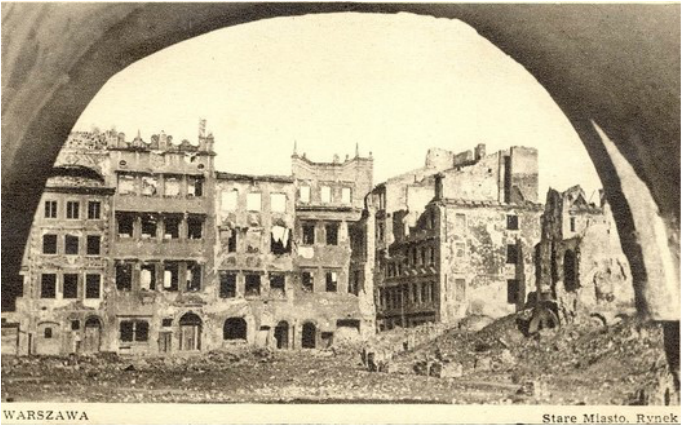

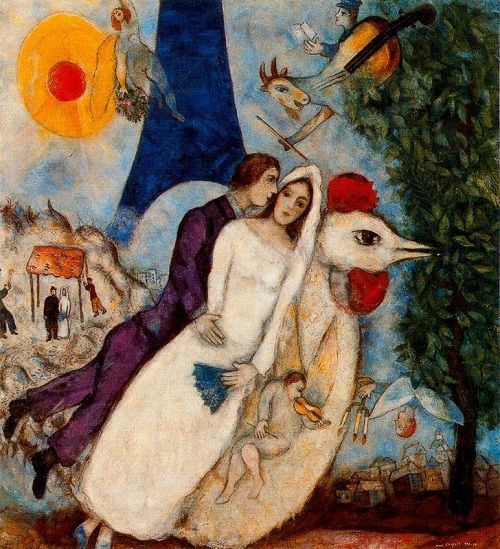

When I was growing up, I was perpetually fascinated by matters relegated to realms unknown. Namely, this applied to such phenomena as witchcraft, psychic dreams, ESP, curses, and other related and unexplainable activity. In part, I believe that this fascination stemmed from the stories my father would make up to lull my younger siblings and me to sleep at night, as well as the folktales – some of them quite frightening – that I used to enjoy reading when I was relatively young. But mainly, I was piqued from early-on by the unusual occurrences my maternal grandmother, Tola Pszenica Pinkus (b. Warsaw, 1921-d. Chicago, 1999), related to me about her family and herself, growing up in pre-World War II Warsaw, Poland. I always found these unusual occurrences all the more intriguing, given that my grandmother hailed from an upwardly mobile and well-educated Chasidic family that was fairly modern and well-integrated in Polish – and particularly, in Warsaw Jewish – society. Indeed, my grandmother attended Polish public schools and was on the verge of entering her final year of Gymnasium [a college preparatory high school] when World War II broke out on September 1, 1939. What’s more, her father was a polyglot who knew seven languages, a businessman, and medically-trained man who was revered for his knowledge, both by local Jewish and Gentile Polish society. Supernatural occurrences and beliefs are often associated with small-town shtetl life or those who are deemed highly emotional, impressionable, backward, and possibly also rather ignorant and/or poorly educated. These stereotypes simply did not hold sway with my grandmother or members of her family.  Illustration of a woman immersed in a vivid dream. (Courtesy of Beyond the Borderline Personality, accessed 5-5-17.) Illustration of a woman immersed in a vivid dream. (Courtesy of Beyond the Borderline Personality, accessed 5-5-17.) The accounts that I heard most frequently within the realm of “the unknown” pertained to what may be deemed the “psychic dreams” of my grandmother and some of her close Pszenica family members. Given that my grandmother had what I considered the “gift of second sight” – something that appeared to run in her paternal family – I often wondered, as a child, whether I too would ever show signs of this “gift.” On at least one occasion when I mentioned this to my grandmother, she became somewhat irritated with me and responded in her typical matter-of-fact Warsaw Yiddish and slightly-accented English: “Believe me, Rivka, you do not want or need such a gift! S’iz behopt nisht ka’ matune! (It’s no gift at all!)!” When I would then declare my grandmother a “witch” (makhasheyfe in Yiddish) – since witches are said to possess powers of the unknown – my grandmother would usually scoff at me with some of her most typical Yiddish expressions: “Hak mir nisht in shvakhn kop (aran)!” (Literally: “Don’t bang my weak head!”; figuratively: “Stop pestering me!”), “Hak mir nisht ka’ tshaynik!” (Literally: “Don’t bang the tea kettle at me!”; figuratively: “Don’t bother me!”), and “Vus redsti aza narishkaytn?!” (“What are you talking such nonsense?!”). As indicated by my grandmother’s aforementioned reactions, one might say that she viewed this “gift” as perhaps more of a curse than anything else, and that she did not consider this something worthy of my taking it as seriously as I did. Apparently, my grandmother herself had several such unusual dreams throughout her lifetime, beginning from when she was a relatively young girl of perhaps 10, and lasting up until the 1950s – at least – in her post-World War II life in Chicago. The earliest such account that I heard numerous times (because I asked my grandmother to retell it on multiple occasions) was that of the dream that my grandmother had when she was a child and had contracted scarlet fever. As my grandmother conveyed to me, scarlet fever was a potentially fatal disease that children of that place and era (Warsaw, early 1930s) often did not survive; and those who did, were often left brain-damaged, deaf, with heart-damage, and/or a host of other lifelong maladies. During the course of a single night, my grandmother’s temperature rose to a dangerously high level, such that the consulted doctors did not believe that she would survive this ordeal – and that if she did, she would essentially be left a “human vegetable.” As she lay in bed in a comatose-like state, my grandmother had a dream in which she witnessed her namesake, Tobe Sure Pszenica, the mother of her paternal grandfather, Rachmiel Yosef Pszenica. The first Tobe Sure (my grandmother being the second) had died relatively young, even before my grandmother’s father, Toivye Gitman, was born. Therefore, the only immediate physical witness at the time to this foremother was that of my grandmother’s grandfather. After all, there were no photos dating back that far, and I am uncertain how many photos the family had in general, given that photos were not terribly cheap, nor were they as widely accepted among Chasidic Jews (like my grandmother’s family). Indeed, when I asked my grandmother about family photos, her pragmatic and to-the-point remark was: “Ver hot dentsmul gehat gelt ts’ makhn bilder?!” (“Who had the money in those days to make photos?!”) In the dream, my grandmother’s namesake comforted her by presenting her with some beautiful well-ripened plums, saying: “Eat these nourishing plums, my dear, and you will soon be well again. Do not be afraid” – similarly, in Warsaw Yiddish: “Es di flomen, man tayerinke, un di vest bald zan gezint. Hob nisht ka’ moyre.” My grandmother heeded her great grandmother’s words and ravenously bit into the succulent fruit. All the while, as this dream was transpiring, my great grandfather, Toivye Gitman Pszenica and a quorum of adult males stood vigilante at my grandmother’s bedside reciting Psalms throughout the night. Finally, at some point, my grandmother’s fever broke, and she awoke shouting that she had seen “Bubbe [Grandmother] Tobe Sure,” her namesake. My great grandfather was very much moved by my grandmother’s account – especially since he himself had never known this first Tobe Sure. He, in turn, related the details surrounding my grandmother’s dream to his own father, Rachmiel Yosef, the son of the first Tobe Sure. When Rachmiel Yosef heard the physical description of the woman who appeared in my grandmother’s dream – especially, of the sheytl [wig] and brown jumper that she wore – he recognized all of this to be the mother whom he had known, and who had died many years before. He jumped up, exclaiming: “I know precisely which jumper you are talking about. This was an article of clothing my mother used to wear quite frequently.” Afterward, he went to search among old boxes of his departed mother’s belongings and found the exact brown jumper that he had had in mind. He brought it to my grandmother, who in turn confirmed that yes – this was, in fact, the very article of clothing that she had witnessed in her dream.  Jewish undertakers converse next to a pile of wooden coffins in the Warsaw ghetto. Over time, as mortality rates in the ghetto increased, burials in the Warsaw Jewish Cemetery were generally performed in mass graves. (Courtesy of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, accessed 5-6-27.) Jewish undertakers converse next to a pile of wooden coffins in the Warsaw ghetto. Over time, as mortality rates in the ghetto increased, burials in the Warsaw Jewish Cemetery were generally performed in mass graves. (Courtesy of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, accessed 5-6-27.) I believe that until her dying day, my grandmother credited her own great grandmother and namesake for looking over her and ultimately, for saving her young life through the power of that very real dream. A few years after that dream episode, also in the 1930s, my grandmother’s father showed her the headstone of the first “Tobe Sure Pszenica,” whose grave stood in the Warsaw Jewish Cemetery. As a postscript to this story, I have personally made several efforts to locate that grave on my multiple trips to the still-intact Jewish cemetery on Okopowa Street, but to-date, I have not been successful in locating it. Yet another story involving a “psychic dream” that my grandmother had before the Second World War, most likely a few years after the former dream, did not have such positive results. In this other dream, my grandmother unknowingly predicted the death of her maternal grandmother, Roize Urfajg Pinkiel. In the disturbing dream that my grandmother had one particular Friday night, she witnessed an undisclosed lifeless figure lying in bed surrounded by a large crowd of sobbing people. Among these individuals was her mother, Miriam Pinkiel Pszenica, hunched over the lifeless figure and sobbing uncontrollably. Not surprisingly, my grandmother woke up shaken, but I am not certain that she ever discussed the dream with any other family members. It was the regular custom in my grandmother’s family on the Sabbath [Shabes, in Yiddish] that her maternal grandmother would walk over to the Pszenica household following lunch, and the family would gather together, chat, take walks, and the like. But on this one Saturday afternoon following the night during which my grandmother had that frightful dream, Bubbe Roize did not show up at her usual time. Not long thereafter, there was a frantic knock at the apartment door, and a messenger appeared to inform Miriam Pszenica – my grandmother’s mother – that she had to come quickly, as her mother had suddenly become gravely ill and needed her daughter at her bedside. Bear in mind that up until that time, according to my grandmother, her maternal grandmother had never been seriously ill. Yes, she did adhere to cupping – also known as bankes in Yiddish – which was considered a remedy for circulatory problems, but otherwise, she was a rather fit woman. Thus, her illness took the entire family by complete surprise; it was not something that anyone could possibly have predicted beforehand. She had somehow developed an inflammation of the intestines, and in a matter of hours she was dead. Indeed, her daughter Miriam was at her bedside – just like my grandmother had dreamt the previous night – when she passed away. My grandmother’s menacing nighttime vision had in reality come to pass…  Warsaw Jewish Cemetery on ul. Okopowa, recently restored headstone atop the grave of my great great grandfather, Rachmiel Yosef Pszenica, who perished in the Warsaw ghetto in 1941 (b. 1866-d. 1941). (Photograph courtesy of Rivka Schiller, fall 2014.) Warsaw Jewish Cemetery on ul. Okopowa, recently restored headstone atop the grave of my great great grandfather, Rachmiel Yosef Pszenica, who perished in the Warsaw ghetto in 1941 (b. 1866-d. 1941). (Photograph courtesy of Rivka Schiller, fall 2014.) This was the only one of my grandmother’s four grandparents to die before the onslaught of the Warsaw ghetto. The other three were murdered in the early years of World War II/ the Holocaust. One of those other grandparents to die in the war was the aforementioned Rachmiel Yosef Pszenica, who passed away in July of 1941, and whose grave I visited in the Warsaw Jewish cemetery in 2014. In my grandmother’s opinion it was a great blessing for her departed grandmother to have died in the years leading up to the khurbn [Yiddish for a great catastrophe – the Holocaust]. In her words: “At least she was not murdered, but died of natural causes.” Sadly, I have to agree that my grandmother was correct. It was, in fact, a year after Bubbe Roize Pinkiel died that the family held a ceremony at the Warsaw Jewish cemetery to erect her headstone (or matseyve, in Yiddish). At that time, my grandmother’s father took her aside to show her the grave of her namesake, Tobe Sure Pszenica. This was the same woman whom I previously mentioned that saved my grandmother’s life through yet another “psychic dream.” Another remarkable dream my grandmother had, which also came to fruition, took place at the tail end of World War II, the night before she and her younger sister, Lola, were liberated by members of the Soviet Army in early May of 1945. By this point in time, my grandmother and great aunt had just been on a series of death marches ranging from Auschwitz to the Ravensbrück concentration camp, and other sub-camps. My grandmother was so ill and swollen from starvation and malnourishment that she was ready to give up and die. But during that last night of captivity she dreamt that her father, who had been dead already for a few years, having died of starvation in the Warsaw ghetto and been buried there in a mass grave, came to her and told her not to give up hope, for in the morning she would be rescued by three Jews. As it turned out, the following morning my grandmother was approached by a Russian soldier who informed her that he was a fellow Jew, that he had two accompanying Jewish fellows – also officers in the Soviet Army – and that they had come to liberate them. I do not know for certain what the common language was, but I would imagine that Yiddish may very well have factored into their verbal exchange. As my grandmother was to learn from this and subsequent dreams, whenever her departed father came to her in a dream, it was a sign of encouragement and strengthening, and that things would ultimately be alright. Conversely, when my grandmother was visited in a dream by her departed mother, it was a sign of warning that difficult times were ahead. Some years later, once my grandmother was already living with my grandfather, young mother, and my infant uncle in Chicago in the early 1950s, she had another one of these prescient dreams. This time around, though, she was visited by her mother, which as I just mentioned, was an omen of something ominous to come. In that “psychic dream” – the last of the ones about which I know anything – my great grandmother warned my grandmother that she would soon be met with a very trying and troubling year ahead. As I understand it, not long thereafter, my grandfather developed a rather pernicious form of TB. This was actually a recurrence of the tuberculosis he had developed during the war years, and for which he had endured multiple surgeries yet in postwar Germany. As a result of this highly contagious disease, my grandfather was placed in quarantine in the Chicago-Winfield Tuberculosis Sanatorium, located on the far-outskirts of the Chicagoland area. As my grandmother recalled, the sanatorium was only accessible to her by train, and the train only came once on the hour and only during certain hours. At the time, she had no vehicle, had two young children at home, had no source of income, and had few people to whom to turn for help. During that inauspicious year, the doctors at the sanatorium had little hope of my grandfather’s ever leaving in an upright position. What’s more, the bed that he was given still had the name tag of the previous patient attached to it. The unfortunate individual had also been a Holocaust survivor, and he had not pulled through. It goes without saying that none of this boded well. Furthermore, it all weighed heavily upon my grandmother. To make matters worse, my grandmother had brought my mother along on one of her visits, but because my grandfather was in quarantine, my grandmother and mother had to remain outside, waving to my grandfather at the window. This left my young mother in tears – not understanding why her father did not want to see her. From that point forth, my grandmother informed me that she could not bear to take my mother along with her anymore on those visits. It was simply too heartbreaking and painful for her. Ultimately, though, my grandfather proved the doctors wrong and recovered from the disease – but not before having to undergo more surgical procedures. Once he finally returned home from the sanatorium nearly a full year after having been admitted there, my uncle, who was two years old by that time, could not remember his father and ran away from him. As the story goes, my grandfather was able to lure in my uncle by showing him a pocket watch, which apparently fascinated my uncle and won him over. Although my grandfather miraculously survived that horrible year and returned home to his wife and two children, the dream that my grandmother had had with her departed mother had undeniably been fulfilled.  "Jacob’s Dream." Painting of the Biblical figure, Jacob, immersed in his famous dream of angels climbing up and down a ladder that reached into the heavens. (Courtesy of Pinterest, accessed 5-5-17.) "Jacob’s Dream." Painting of the Biblical figure, Jacob, immersed in his famous dream of angels climbing up and down a ladder that reached into the heavens. (Courtesy of Pinterest, accessed 5-5-17.) These are but some of the unusual accounts that were handed down to me via the oral tradition by my grandmother. I am the first one, as far as I know, to set down any of these stories in the written form. All of these particular accounts revolve around “psychic dreams” – dreams that carried with them a vision of something that was yet to come in the near future – whether for the better or for the worse. But there were still additional family accounts that my grandmother conveyed to me, which involved curses (“kloles,” in Yiddish), the “Evil Eye” (“Ayen-hore,” in Yiddish), name changing for the purpose of fooling the “Angel of Death” (“Malekhhamoves,” in Yiddish), and other such seemingly bizarre happenings. However, for the sake of brevity, I have had to limit the scope of this subject. I am sure that in my readers’ research into their own family histories, they have also come across unusual or unexplainable accounts such as the ones I have related here. These are undoubtedly the stories that help form a more nuanced mosaic of one’s genealogy, as they offer true insight into the human beings behind the names on the family tree, and the lives they led. Moreover, these are the types of accounts that have, at least in part, shaped generations of a family. I am curious to learn more about your own such accounts, and hope that you will please consider sharing snippets of these in my blog’s “Comments” section. If you have any Yiddish materials – perhaps even bearing family accounts of unusual or seemingly unexplained events – that you would like translated, please feel free to contact me at: rivka@rivkasyiddish.com.

28 Comments

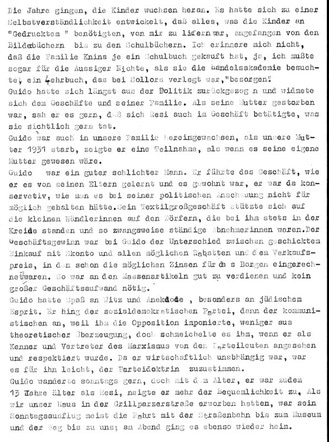

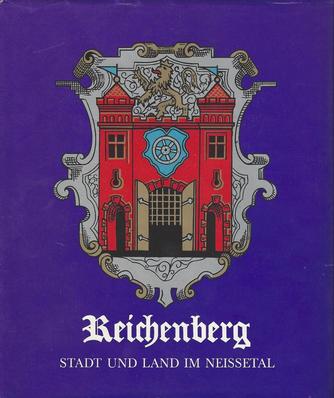

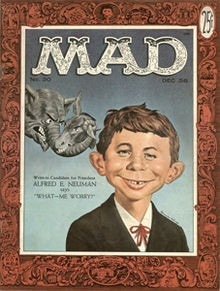

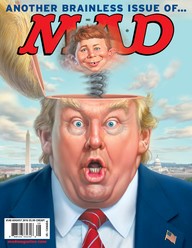

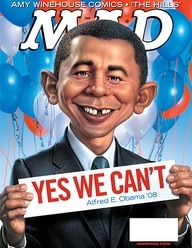

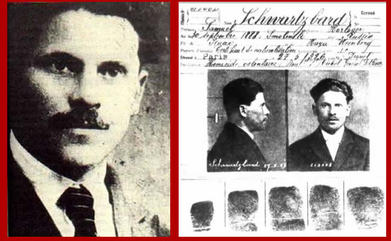

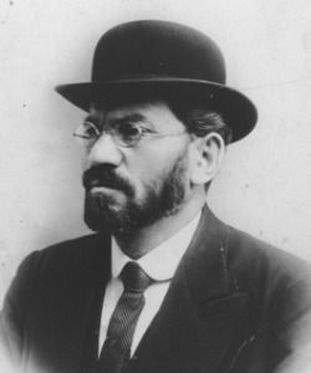

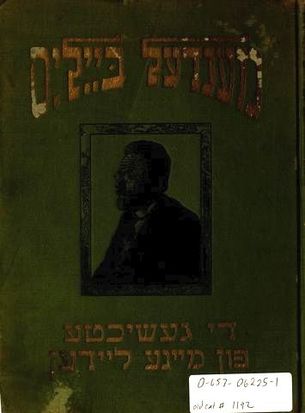

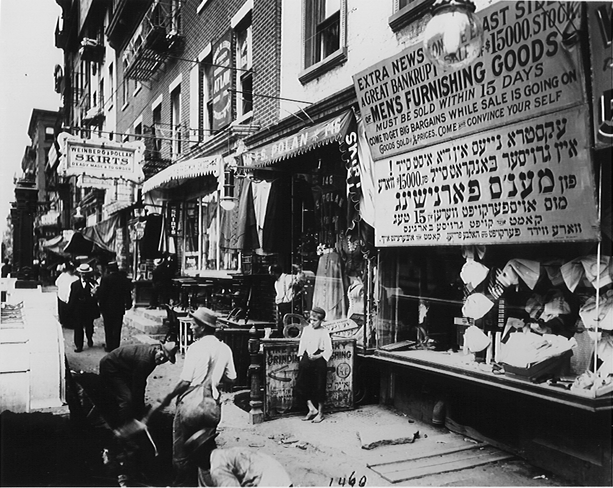

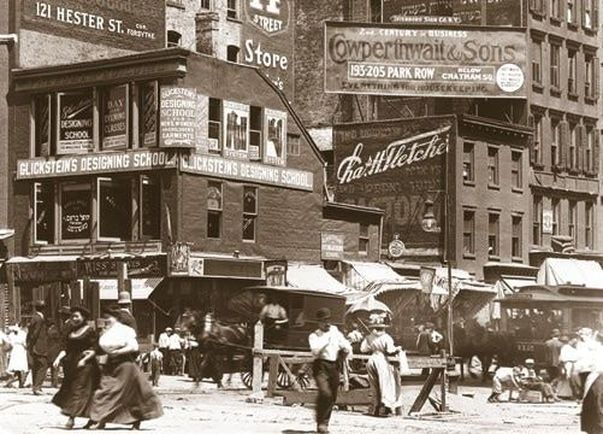

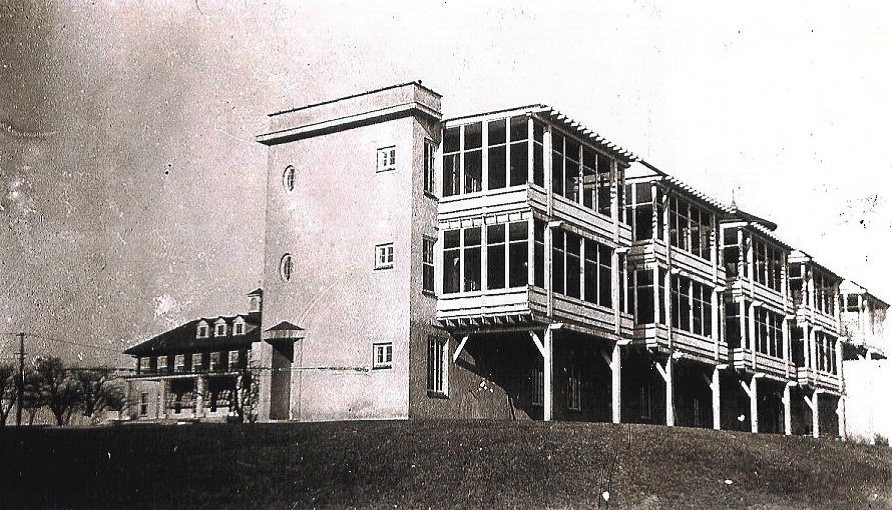

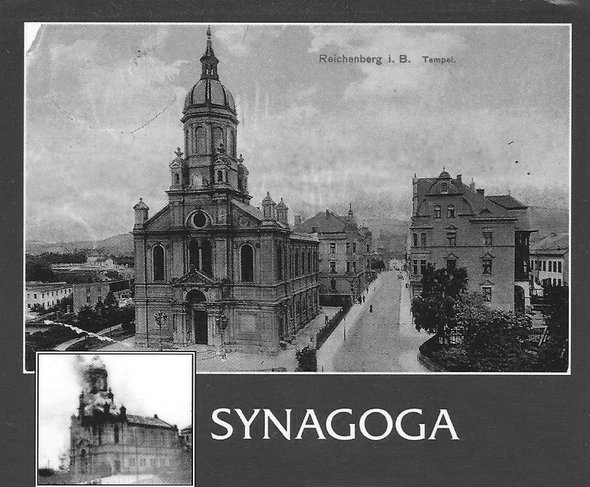

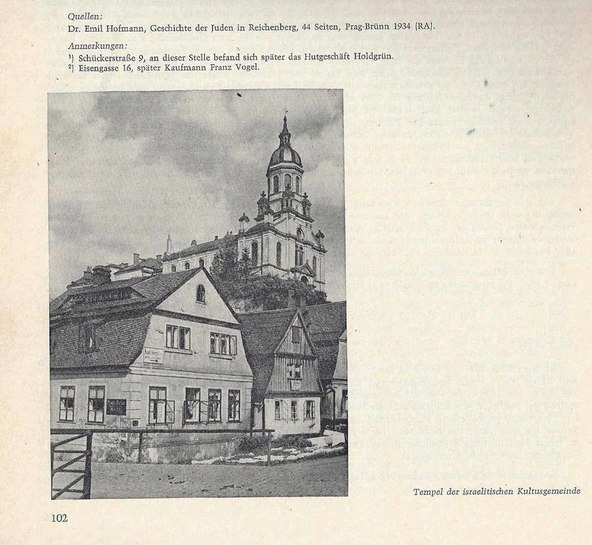

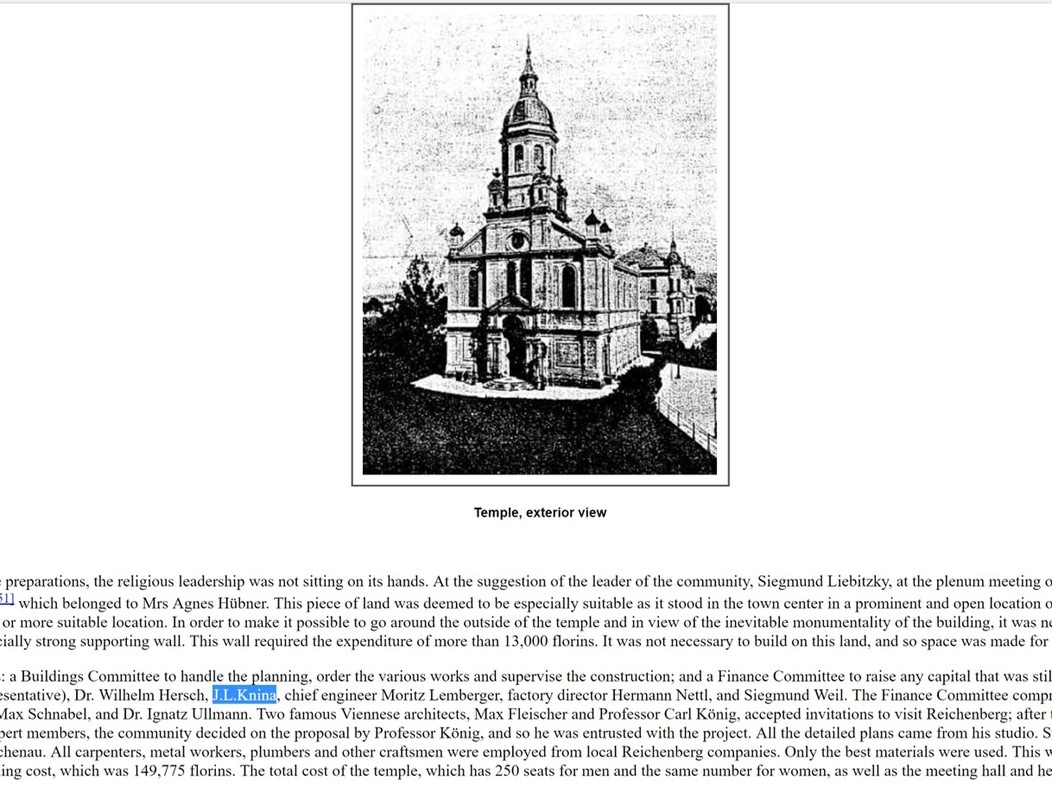

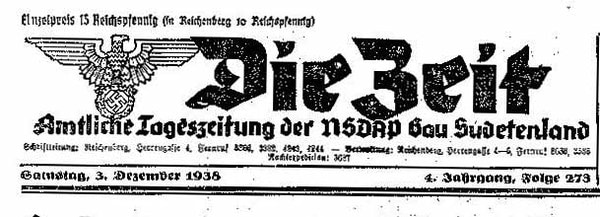

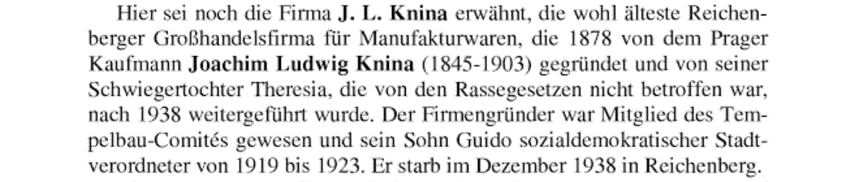

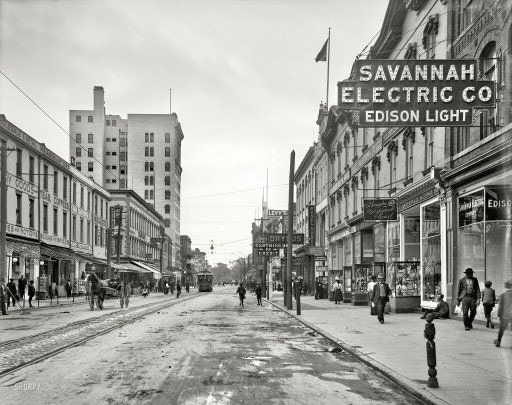

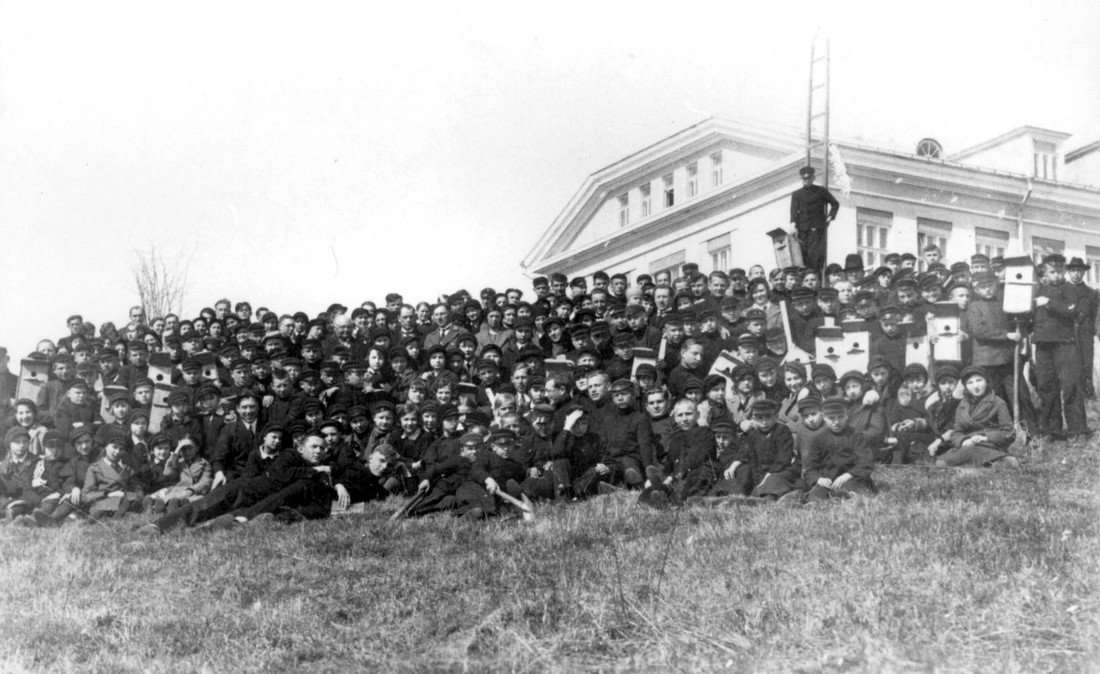

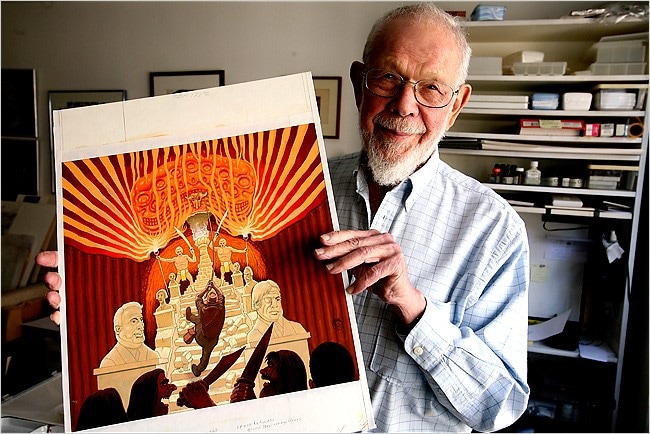

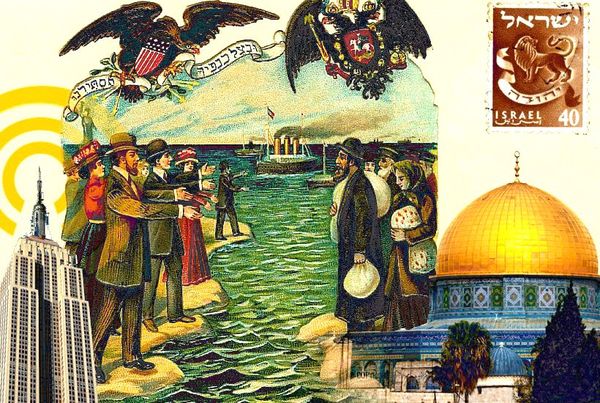

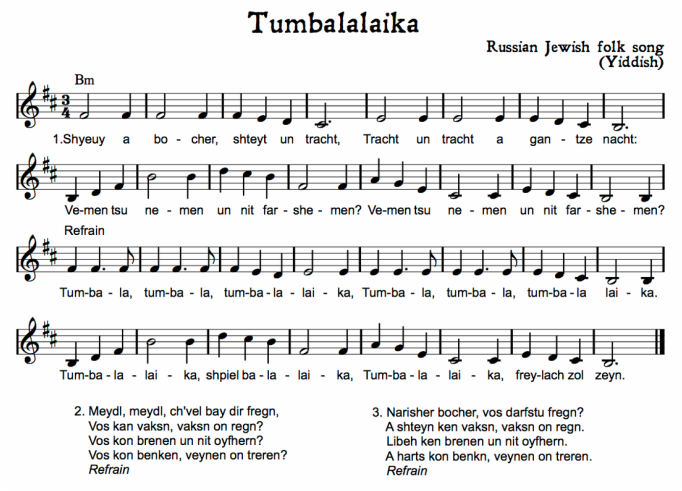

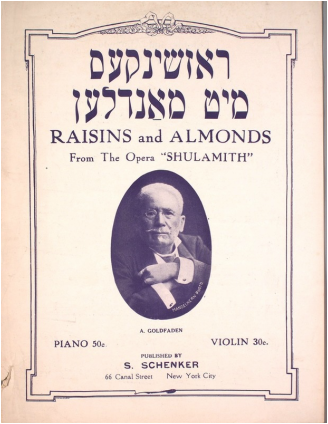

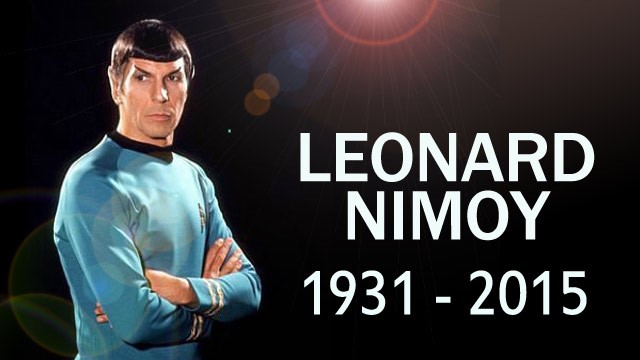

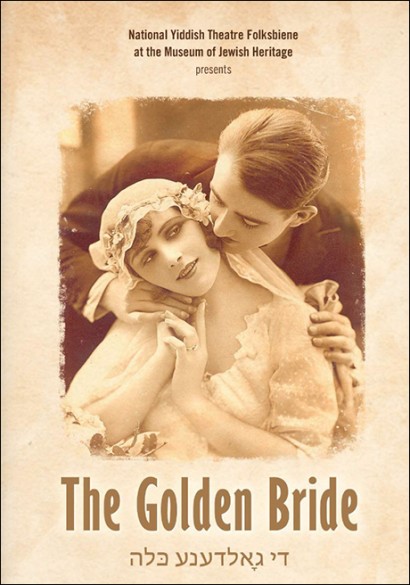

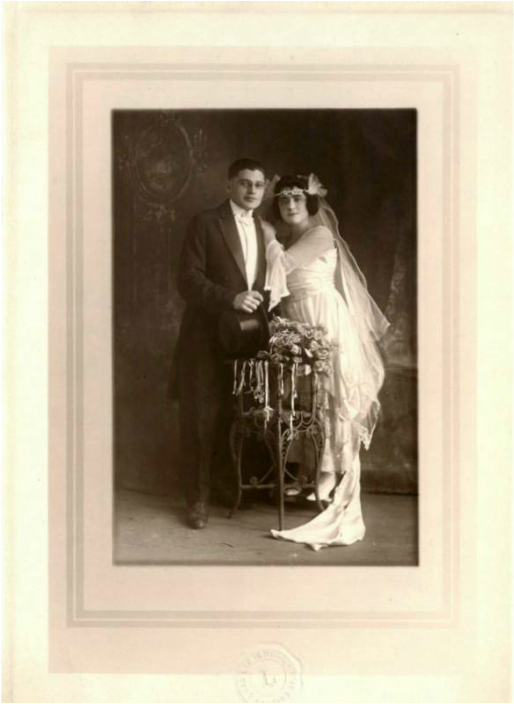

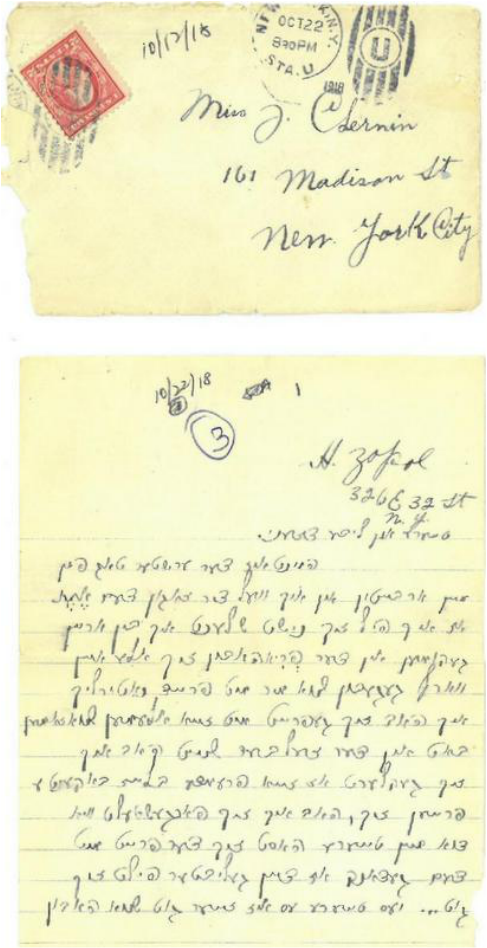

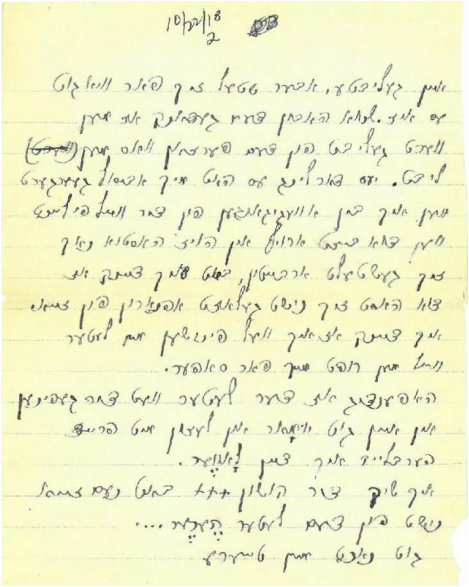

In this month’s blog, I am doing things a little bit differently than I normally do. More specifically, I am sharing with you the guest blog of a good friend of mine, Annette Gendler, who just published her first book, Jumping Over Shadows: A Memoir, which I highly recommend you all read. Without giving away too much about the book’s plot, let’s just say that it revolves heavily around Annette’s genealogical journey and quest for answers about her family’s past in pre-World War II and wartime Czechoslovakia. The work also pertains to questions about identity – and more to the point – about Jewish identity. These are all topics that I have discussed in one form or another in my own past blog articles (see, for instance, my January 2017 blog), as featured in “Forays into Yiddish.” I invite my readers to please take the time to read Annette’s most engaging and well-researched article about her family history in the following blog. Please also feel free to share your own thoughts and comments at the end of this fascinating piece. I always knew that my German great-aunt had been married to a Jewish man in Czechoslovakia before World War II because that marriage had put the extended non-Jewish family, particularly my grandparents, in danger once the Nazis took over their hometown of Reichenberg (now called Liberec). The city turned into a veritable Hexenkessel (witches’ pot) when it was declared “Gauhauptstadt,” i.e. capital of the German Reich’s new region, the Sudetenland, after that area was ceded to the German Reich following the infamous Munich Agreement of September 1938. It wasn’t until my great-aunt’s story resonated in my own life that I began to wonder about this family story when I, living in post-WWII Germany, fell in love with and married a Jewish man. And later, when I decided that this impossible love between a German woman and a Jewish man happening twice in my family would make a good story, I had to try to put it together. What had really happened to my Jewish great-uncle? And what happened to their marriage when the Nuremberg Laws, prohibiting marriages between “Aryans” and “non-Aryans” took effect? Growing up, I was close to the daughter of this marriage, my dad’s first cousin Herta, who told me many family stories. So did my grandmother, who was a gifted storyteller. Nevertheless, being aware of family stories is one thing, being able to retell them and fit them into a historical timeframe is another. For example, when I traveled to Reichenberg for the first time in 2002 and called Herta from a stunningly beautiful café there, she said: “Oh yes, that must be the Café Post. You know, my father loved to go there. He went there every Sunday morning. Met with friends. My mother didn’t quite like this, but that was his habit. Until of course he couldn’t go anymore. But that’s how things were then.” “That’s how things were then”—by this she meant that a man like her father, Guido Knina, who had been part of the bourgeois coffee house culture, couldn’t go to the Café Post anymore after Reichenberg had fallen under Nazi rule because he was a Jew. Under the laws of the German Reich, Jews were banned from public places like cafés. When I later visited Herta in the nursing home, she mentioned, “I always wanted to go to university; I would have loved that. But in those days it wasn’t possible, so what could I do?” Characteristically, she did not mention that in the 1940s, in a Czechoslovakia annexed by Nazi Germany, she was not able to study because, classified as a half-Jew, she was barred from institutions of higher education. Only when I read my grandfather’s memoirs, typed on now yellowed onion skin paper, did I find out that my grandfather had, in fact, arranged for her to be able to get a degree from the Handelsakademie (Academy of Commerce) even though technically she was barred from that, too. But the principal was a cousin of my grandmother, and he agreed to let Herta attend unregistered.  Page from my grandfather’s memoirs that also appears as front matter in "Jumping Over Shadows." Page from my grandfather’s memoirs that also appears as front matter in "Jumping Over Shadows." Those were the intersections of Jewish and non-Jewish life that interested my grandfather, and that he duly recorded in his memoirs because they affected him. I based a lot of my reconstruction of my great-aunt’s story on my grandfather’s memoirs, and specifically a chapter he titled “My Sister.” Very quickly, however, I realized that I needed to fill in the blanks if I wanted to contrast my story of falling in love with a Jewish man with my great-aunt’s. Who had he been? Who had his family been before they became connected with my family? In order to round out the story of this Jewish side of the family, I needed to know more about the Jewish community of Reichenberg. My first find, on the German eBay site, was this book on Reichenberg, published in Augsburg in 1974. I’m fortunate that I am fluent in German, and that my sister, who still lives in Germany, was willing to purchase the book for me. In it, I found several passages that corroborated other parts of my grandfather’s narrative, but it also included a chapter on “Die israelitische Kultusgemeinde in Reichenberg” (the Israelite Cultural Community in Reichenberg). Side note: To this day, Jewish communities in Germany, Austria and Switzerland are called “Israelite,” not “Jewish.” I have often had the impression that the word “Jude” (Jew) is hard to utter for Germans.  Book about the city of Reichenberg published in Augsburg, Germany in 1974. Book about the city of Reichenberg published in Augsburg, Germany in 1974. In seven paragraphs, this book summarizes the history of the Jewish community in Reichenberg. It was the usual sordid tale of rights granted and rescinded, coupled with various harassments, until Jews were given full citizenship by Austro-Hungarian Emperor Franz Josef in 1860, and 30 Jewish families took up permanent residence in Reichenberg. At the time, Reichenberg was a well-to-do center for textile and glass manufacturing and trade. However, these seven paragraphs didn’t give me any specific information on the family I was looking for. The chapter also featured this image of the “temple of the Israelite community.” Most importantly, for my research, it cited its source, an article written by Dr. Emil Hofmann, “Geschichte der Juden in Reichenberg,” published in 1934 (see above the picture where it says “Quellen:” – “Quelle” means source.) I was able to find this article, The History of the Jews in Reichenberg, in translation, on Jewishgen.org as part of a collection of articles titled The Jews and Jewish Communities of Bohemia in the Past and Present, edited by Hugo Gold and also published in 1934. Here I struck gold: “J.L. Knina” was listed as a member of the temple’s building committee. “J.L. Knina” was Joachim Ludwig Knina, father of my great-uncle Guido Knina. Further on, in a chapter titled “Jews in Non-Jewish Organizations,” I found Guido himself: From my grandfather’s memoirs I knew that he and Guido had served as city councilmen together. However, I did not know that Guido had been the first Jew elected to the city council. This is the kind of information that would be noteworthy to a Jewish audience but not to my grandfather. In addition, my grandfather was loath to label people—another reason, perhaps, why he makes no mention of this. This is where research is needed to fill in the blanks and find the information that is neither part of family lore nor contained in family documents. Ordering books, viewing them online, or borrowing volumes on Czech history from the library was, however, not enough. I had to hit the archives. On one of my trips to Reichenberg, in 2009, I went to the public library there, and asked whether they had newspapers from 1938. I thought if I could read reports from that time, I would be able to recreate what life had been like back then. The archivist shook her head and told me that it was unlikely they would have anything because there had been a fire at some point (Now the library is housed in a shiny new glass and steel building.). But she did put in a request and told me to return in two hours. When I got back, she gesticulated that they did have something, and after surrendering my American passport as a guarantee, she handed me a huge ledger of yellowed newspapers from 1938. Actual, physical newspapers! Thankfully, I can read the old Gothic-style German print; as a kid, growing up in Germany, I had been determined to read one of my favorite books, my grandmother’s volume of the saga of Rübezahl, a red-headed giant who lived in the forested mountains surrounding Reichenberg. Even though I knew that from September 1938 on, Die Zeit, Reichenberg’s city newspaper, had been a Nazi organ, it was still a fascinating read. The November 11, 1938 edition gleefully described the destruction of Reichenberg’s synagogue during Kristallnacht: Note here the particularly chilling subtitle: “Only the walls are left standing—the population protests the Jewish murderous attack” referring to the pretext for the pogrom of Kristallnacht, the assassination of German diplomat Ernst vom Rath by Herschel Grynszpan, a 17-year-old Polish Jew, in Paris on November 7, 1938. As far as I know, Guido never found out that the synagogue his father helped build went up in flames. He was already in a sanatorium, suffering from diabetes, and in and out of consciousness. My grandmother spent that day at his bedside. By that time, he and my great-aunt were divorced, presumably so she, the “Aryan,” could take over his textile business, save the family’s livelihood and ferry her half-Jewish children through the Nazi inferno. Most of Reichenberg’s Jews perished in concentration camps. I know of only one of Guido’s cousins, who made it to Palestine. My grandmother corresponded with her, and my husband and I visited her in Haifa on our first visit to Israel together in 1986. In 2012 (my manuscript was already finished), another book on the history of the Jews of Reichenberg was published: Reichenberg und seine jüdischen Bürger by Isa Engelmann, Berlin, 2012. It confirms the family story that Guido’s wife, my great-aunt Theresia (called Resi by my family), took over the business Joachim Ludwig Knina had founded in 1878 and that his son Guido had run until 1938: In order to keep up appearances, Resi had no contact with Guido after the divorce. Instead, my grandparents took care of him. They bribed the staff so he could stay in the sanatorium (Jews were barred from all kinds of institutions by then) and when he passed away in December 1938, they arranged for his funeral. Many years later, his son Ludwig, the only relative to remain in Reichenberg all his life, had my family’s and Guido’s grave put together because, after the war, German graves were regularly vandalized. Now the family gravestone only reads “Rodina Kninova” (Family Knina); unless you request to see the register for this particular grave, you would never know that my family members with the last name Berndt are also buried there:  Again, one piece of evidence, namely the grave, tells only part of the story. The associated document, if you do ask for it, tells another part of the story, namely that in fact more than just “Rodina Kninova” are buried there. But even that is only part of the story. Nowhere, except in my family’s oral history, will you find that Guido, buried here, was Jewish. It all needs to come together—artifacts, documents and lore—to round out the picture. And even then, I am not convinced it is the whole story. What remains of a life, of all lives, are always fragments. Once a subsequent generation finds these fragments, it depends on them, on how they piece them together, what story might be told of the past in the future. I, for one, stumbled upon one stunning fragment that could explain another tragic family story. For that tale, however, you will have to read Jumping Over Shadows.  Annette Gendler is the author of Jumping Over Shadows, the memoir of a German-Jewish love that overcame the burdens of the past. Her writing and photography have appeared in the Wall Street Journal, Tablet Magazine, The Forward, Kveller, Bella Grace and Artful Blogging, among others. She served as the 2014–2015 writer-in-residence at the Hemingway Birthplace Home in Oak Park, Illinois, and has been teaching memoir writing at StoryStudio Chicago since 2006. Born in New Jersey, she grew up in Munich, Germany, and lives in Chicago with her husband and three children. About a year ago at this time, I interviewed two recently emerged and international musical performers, Saul Dreier and Ruby Sosnowicz, of the “Holocaust Survivor Band.” For those of you who did not have the opportunity to read that blog, you may access it here. In the tradition of that piece, I decided to interview – this time in-person – yet another prominent name in the world of art and performance that also bears close ties to Yiddish and to pre-World War II Eastern Europe. The central figure in this month’s blog is that of Al Jaffee, who is perhaps best-known for his work as a writer-artist for the satirical American humor magazine, Mad (magazine). Readers and non-readers alike still recognize the long-running publication for its iconic mascot, “Alfred E. Neuman,” who continues to appear in some form or another on the magazine’s front cover. Mad’'s longest-running contributor is, in turn, Al Jaffee, whose work with the magazine debuted in 1955. Al has worked consistently for the publication since that time, with the exception of a brief period between 1957 and 1958, when he worked elsewhere. Indeed, in 2016, Al’s career earned him a place in the Guinness Book of World Records as the longest active comic artist.  Issue #30 (December 1956) of Mad, the first one to feature the magazine’s mascot, Alfred E. Neuman. (Courtesy of Wikipedia, accessed 3-24-17.) Issue #30 (December 1956) of Mad, the first one to feature the magazine’s mascot, Alfred E. Neuman. (Courtesy of Wikipedia, accessed 3-24-17.) However, what most people who have heard the name “Al Jaffee” do not know about him is that he has led not only a highly productive and creative life, but also a most unusual life, which began in Savannah, Georgia on March 13, 1921. One of the things that makes Al’s life less-than-typical is that his childhood was split between an American English-speaking world and a small-town Lithuanian shtetl life in which Yiddish was the lingua franca for the vast majority of Jews. Al’s parents, Morris and Mildred, had immigrated to the United States sometime before World War I from the remote and impoverished Lithuanian town of Zarasai (also known by several other monikers, including: Ežerėnai [Lith.], Ezhereni [Yid.], and Novo-Aleksandrovsk [Rus.]), and settled in Savannah, Georgia, where Morris Jaffee got a job at what was initially Blumenthal’s Pawn Shop. Subsequently, it became a department store, and Morris was given a managerial position. Then in 1926, Al’s mother, whom Al described as fervently religious and far more “old world” than his Americanized father, up and took Al and his three younger brothers with her back to Zarasai. This trip only lasted until 1927; but subsequently, in 1928/29, she once again took the children with her to her hometown in Lithuania. This trip was not intended to last a long time, yet it ultimately resulted in Al and his brothers spending several of their formative years in the town referred to by different sources as “The Switzerland of Lithuania.” The Jaffee family’s final year in Lithuania culminated in a period of residence in the predominantly Jewish Kovne (Yiddish for Kaunas) suburb of Slobodka. For those interested in the history of Jewish life in Lithuania, Slobodka is perhaps most often associated with the “Slobodka Yeshiva,” which functioned from ~1881 until the outbreak of World War II. Al’s sojourn in Zarasai and Slobodka lasted until May of 1933, at which time his father returned to Lithuania to reclaim his family. Al’s father saw the handwriting on the wall, as Adolf Hitler had just come to power in January of that year, and he insisted on bringing his family back to safer grounds in the United States. Unfortunately, Al’s mother refused to return to the United States or to allow her youngest son to return in the company of her husband and other sons to the United States. The youngest son was later brought out of Lithuania in 1940, scarcely before the outbreak of The Second World War. Al’s mother, however, was murdered with the roughly 95% of Lithuanian Jewry, in the Holocaust. During the time that Al spent in Lithuania, he spoke English at home with his mother and brothers, as this had also been their spoken language at home in Savannah. Al’s father was, in fact, quite fluent in English, and even wrote letters in English for other immigrants who had not (yet) mastered the language. Al’s mother also enjoyed reading English, and asked that her husband send English-language children’s books from the United States for their four boys. Somewhat surprisingly to me, Al remarked that back home in Savannah, his family spoke English – not Yiddish – nor did he hear Yiddish spoken during his time in Savannah. This, of course, presented certain linguistic challenges when Al and his family relocated to Lithuania. Yet, even as English was the spoken tongue of home life, it was not understood by the locals in Zarasai or Slobodka. As a result, Al also had to learn colloquial Yiddish, which he spoke with his relatives, his boyhood friends, and which was spoken at the Jewish school or “kheyder” (or “cheder”) that he attended. He also learned the language, along with Jewish, and more general subject matter, from a “melamed” – a tutor – who came to the Jaffee home. As Al recalled, life in Zarasai – with the large house his family rented, replete with a sizable orchard, bearing apples, pears, gooseberries, and other such delicacies – was much like an Eastern European Jewish version of the all-American Mark Twain novels. While growing up in Zarasai, which Al described as quite primitive – a place where nearly everything, including ink and fishing rods – had to be made from scratch – he would play, go fishing, and dig for skeletons from The First World War with his friends. All of this was conducted in an unsophisticated day-to-day Yiddish. Russian and a scant amount of Lithuanian, which Al remarked that he almost never heard aside from at the local post office, were also spoken on the streets. But among Jews, life functioned entirely in Yiddish. If one needed the aid of a Gentile policeman, for example, who invariably spoke Russian, Lithuanian, or Polish, it was necessary to somehow make oneself understood in one of these other tongues. Otherwise, though, this was the linguistic exception for Jews at that particular place and time – not the norm. When the Jaffee family relocated to Slobodka in 1932 to live near other relatives, Al once again had to employ the Yiddish-speaking skills he had acquired during his years living in Zarasai. Al’s uncle owned the local “Bango Theater,” a popular entertainment site that featured films and actors from all over, including: Gustav Fröhlich, a popular German actor and film director; Clara Bow, an American actress who started out in silent films and transitioned to “talkies”; Birth of a Nation; and Nosferatu, which totally spooked Al when he saw it in his uncle’s theater. According to Al, Slobodka was a generally nice place in which to grow up, barring the fact that as Jews, it was always necessary to be on one’s guard and wear one’s armor against the potential attacks of anti-Semitic Gentiles, both children and adults. Tragically, during World War II, Slobodka would become a true ghetto for Jews, manned by Lithuanian guards, and containing over 29,000 Jews. A significant number of these individuals were murdered in the nearby Ninth Fort, while others yet were deported to additional murder sites.  Members of Gordonia, a Zionist youth movement, accompany fellow member, Yaakov Miller, as he departs for Palestine from the Kaunas train station, 1938. Hebrew caption indicates that photograph was taken on the “7th of Adar 2,” specifically on “Thursday morning, 9:40 am.” (Courtesy of Eilat Gordin Levitan, accessed 3-24-17.) Notwithstanding the heavily Yiddish-oriented world in which Al found himself in Lithuania, he noted that the last time he actually spoke Yiddish was in 1933, at which time he – as a twelve-year-old child – returned to the United States. Nevertheless, as Al asserted, the seeds of Yiddish were evidently planted deeply enough, so that even today – all these more than eight decades later – he still often thinks in Yiddish. As he put it, “The language has many subtleties that can’t be expressed in other languages.” Al’s examples of this included the Yiddish word “tam,” which stems from the Hebrew: “ta’am.” Depending on context, the word can mean: taste, flavor, charm, or appeal. Another one of Al’s Yiddish-isms, one that was supposedly made up by Mad, was the off-color expression: “puts-rebe” (or “putz-rebbe”). This was apparently something that Al heard while growing up in Lithuania, and which was later appropriated by Al’s colleague, Harvey Kurtzman – who found the sound amusing – for their satirical publication. The expression was used in Lithuania, according to Al, to mean a “jerk of a teacher.” To this day, Al revealed, he is asked by Jews and non-Jews alike about the meaning behind the words. And yet another Yiddish expression that Al shared with me was: “Vos zogt der groyser knaker?” – meaning: “What does the big shot have to say?”  Front cover of June 22, 2016 issue of Mad. (Courtesy of Mad, accessed 3-23-17.) Front cover of June 22, 2016 issue of Mad. (Courtesy of Mad, accessed 3-23-17.) As for Al’s work as an artist-writer, this certainly predated his tenure with Mad. He was always artistic as a child – although, as Al conveyed, he does not enjoy “pretty art” – nor does he view art as a “holy business.” Rather, he sees it as a tool for communication and a vehicle for self-expression. But one of Al’s first major “breaks” in the field of artistic expression actually came from the military, when he served with the United States Army during World War II. It was during that time when he worked for the Pentagon and the Air Force Surgeon General’s office illustrating brochures, pamphlets, flow charts, and designs pertaining to physical exercises created and advocated by Colonel Dr. Howard Rusk (1901-1989), a leader in the field of physical therapy for both military personnel and civilians. Later on, Dr. Rusk and Bernard Baruch (1870-1965) would join forces to create the world-famous Rusk Institute of Rehabilitation Medicine in New York City, which continues to apply Dr. Rusk’s exercises to the medical and physical needs of civilian Americans to this day. During this same period of military service, Al came into contact with several other Jewish fellows serving alongside him, many of whom knew at least some Yiddish. One important figure in particular then was Captain Alfred Fleishman (1905-2002) of St. Louis, Missouri. Fleishman came from a Yiddish-speaking family that owned a company called “Fleishman Pickle Co.” Al recalls how Fleishman once took him to a kosher deli in Washington, D.C., and told him about his family. The two of them would throw around Yiddish terms; and from time to time, Fleishman would give him pickles that he had brought back with him from his family in St. Louis. Al made a point in stating that these types of interactions between different ranks in the military were fairly uncommon.  Front cover of August 20, 2008 issue of Mad. (Courtesy of Mad, accessed 3-23-17). Front cover of August 20, 2008 issue of Mad. (Courtesy of Mad, accessed 3-23-17). In looking for additional information about Captain Fleishman, I uncovered two online obituaries about him in The New York Times and the Los Angeles Times. Both of these articles attest to the fact that Fleishman cut a very decent and honorable figure, that his family operated a pickle company in Missouri, and that he was fluent in Yiddish. What came to light most, though, about Fleishman in those obituaries, is that following World War II, he was assigned by the United States military and the American Joint Distribution Committee (AJDC) – also known loosely as the “Joint” – to Austria and Germany. There, he interviewed Jewish refugees in Yiddish, collecting information for the United States government about how best to assist these individuals. Fleishman spent three months in displaced persons camps engaged in this work; and upon return to the United States, he went on a three-month national speaking tour, soliciting aid for the Jewish refugees. According to one of the obituaries, Fleishman considered heading the delegation to Germany and Austria as his greatest accomplishment. In closing, although he does not continue to speak Yiddish on a regular day-to-day basis today, as he once did in Lithuania many years ago, Al Jaffee still feels driven in his work and in his life by the “Yidishkeyt” (or “Yiddishkeit”) to which he was already exposed during his most formative years. If you have any Yiddish materials – humorous, satirical, or otherwise – that you would like translated, please feel free to contact me at: rivka@rivkasyiddish.com. For those of you who are new to my blog or simply did not have a chance to read my previous post: “Wrestling with Identity: What Happens When Old Country Meets New?,” in which I highlighted several of the major themes and subjects that appear in the documents that I have translated over the past nearly 20 years. One of the main themes that I discussed in that blog was the growing divide that I frequently witness between the older generation – the one that is typically more tied to the “Old World” – and the younger generation – usually the one that is more linked to the “New World.” One of the chief forms of that growing divide may be seen vis-à-vis the traditional, religious observance of Judaism, often referred to as “Yidishkeyt” (literally: “Jewishness” in Yiddish). With the shift from one generation to the next, along with the migration from the “Old Country” to the “New Country,” the threads of religious observance oftentimes unraveled – sometimes, in fact, at a rather quickened pace. Due to space constraints, I was previously unable to showcase all of the examples that exemplified the aforementioned pattern of religious and generational divide, which I had in mind for a single blog. As such, I would like to include in the following, the other excerpt I recently translated for a client from the original Yiddish letter that I left out of my January blog. I am certain that this is a theme that is prevalent in the history of many Jewish families that migrated from Eastern and Central Europe to other parts of the world – the United States, South America, and Palestine (later, Israel) – to name a few. Ironically, this divide is also a theme that continues to repeat itself even today, albeit not necessarily in the same form or manner. Translation Follows: p. 2 With God’s help Warsaw, 1939 …. And now, with regard to my child, I believe that I don’t need to praise her. One must have a good husband for her. The world says that for good things, every person is a man [or possibly a husband]. However, that is not the case … Certainly you know, my son-in-law, and you see what it is to conduct oneself Jewishly. Can you take it upon yourself to lead a pure Jewish life, seeing as I don’t believe that my dear daughter will be able to bear it any other way than what she witnessed [while growing up] in my home? And given that I see that you certainly want her, you love her, this is the first thing [i.e., the matter of utmost concern] that she wants … such that [she] does not want to have any hardship and … one with your leading a Jewish lifestyle. Don’t think that I am such a fanatical person or from such a fanatical family. One can see that from my children and from my sister. But still, the first thing [i.e., highest priority] is a Jewish lifestyle. I have a great deal to write about that, but I believe that you understand what I mean. That having been said, write me whether you can undertake this. At that time, I will agree.  “In Commemoration: 1925,” cover of booklet of postcards in Hebrew and Yiddish commemorating the building of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, which the daughter of this letter's author attended in then-Palestine (Warsaw: Jewish National Fund, 1925). (Courtesy of Kedem Auction: https://goo.gl/JfRNfX, accessed 2-7-17.) “In Commemoration: 1925,” cover of booklet of postcards in Hebrew and Yiddish commemorating the building of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, which the daughter of this letter's author attended in then-Palestine (Warsaw: Jewish National Fund, 1925). (Courtesy of Kedem Auction: https://goo.gl/JfRNfX, accessed 2-7-17.) The above translated excerpt was written by a father in Warsaw, Poland on the brink of World War II, to his future son-in-law in Palestine (also frequently referred to as “Eretz Yisrael”). The father is essentially writing here to his potential son-in-law that he will only grant him his blessing to marry his daughter if the young man is prepared to live a traditional Jewish lifestyle – one that his daughter grew up observing in his household. It is also clear from the translated excerpt that if the potential son-in-law were to respond negatively to the author’s demand, he would not be given a blessing to marry the letter writer’s daughter. As evidenced by other letters written by the same author to the identical son-in-law-to-be, the author wanted the young man to quit his current job and get another one that would allow him to observe the Jewish Sabbath by not requiring him to work then. According to my client, the author’s daughter (my client’s mother) and future husband (my client’s father) came from vastly different backgrounds, though they were both born and raised in Poland. She hailed from an upper-middle class Warsaw family that was religiously observant and was herself well-educated. Conversely, her young man came from a non-religious working class family from Pabianice, a town in the vicinity of Łódź. His education ended by the age of 14, at which time he went to work. He became a hairdresser, often servicing clients who were not Jewish. In contrast, she was accepted to study at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, which in part, prompted her to move to Palestine in 1936. As a postscript, my client informed me that her parents – in spite of whatever differences they may have had – married on June 4, 1939 – within close proximity of when this letter was written. Theirs, according to my client, was a happy union that lasted nearly 50 years. As my client expressed to me, her mother always remained a little bit more religious than her father. But this did not adversely affect their many years together. Aside from the themes about which I have now written, I imagine my readers would also like to know something about the characters who appear in the family letters and other documents that I encounter in my translation work. Not surprisingly, the vast majority of the texts I read pertain to common “everyday” Jews in countries such as Poland (the largest number hail from there), present-day’s Ukraine and Belarus, Romania, Slovakia, Czech Republic, Russia, England, South America, South Africa, Palestine and Israel, and the United States. The characters who are given life – indeed, resurrected and immortalized – through their own words, are frequently businessmen such as the above example, written in Warsaw on the verge of World War II. In numerous other cases, the author is a woman – often a mother writing to one or more of her children – as seen in the example portrayed in my previous blog, written in 1920s’ Kraków. Siblings, grandparents, and other close family members are also included in this lineup of correspondents. However, over the years, I have also occasionally found references to well-known historical figures of various bents: writers, politicians, explorers, victims, heroes, and villains. Some of these individuals are still remembered today, even though they may have lived more than a century ago. It is about a few of these figures that I will now elaborate. 1) Roald Amundsen (1872-1928) – This sturdily-built Norwegian explorer who called himself “the last of the Vikings” was the first person to reach the South Pole on December 14, 1911, which he named Polheim – Norwegian for “Pole Home.” Initially, his country, the rest of the world, and even his own crew, thought that Amundsen’s intended goal was the North Pole. His crew only learned of the true target site when their ship was well off the coast of Morocco and Amundsen announced that they were not headed for the North Pole, but to the South Pole. Amundsen and his crew returned to their base camp some 99 days and 1,860 miles after their departure. Amundsen also achieved other great feats, including successfully sailing through the Northwest Passage in 1903 and flying over the North Pole in 1926. He was ultimately killed while flying on a rescue mission in 1928 over the Arctic Ocean. Ironically, only that same year, he was quoted by a journalist as saying the following about his beloved Arctic: "If only you knew how splendid it is up there, that's where I want to die." No offense to the Norwegians (and perhaps Americans of Norwegian stock), but in all honesty, I wonder how many people today even recall this modern-day Viking. When encountering this name in one of my family letters, I was subtly reminded of one of our local Chicago high schools – “Amundsen High” – about which I had heard while growing up there. But even so, I, too, needed to refresh my memory by reading up on Amundsen. Here is a snippet of the reference to Amundsen that I translated from the original Yiddish in an undated letter written in a reprimanding tone by one brother in Europe to another brother, “Yisroel,” in America: “…. Finally, after such a long [period] of silence, you once again remembered and took a little time, and wrote your brothers a letter. As I see it, in America, it is very hard work to write a letter. One must wait for a letter for a good couple of months. Just like Amundsen, who focuses his speech on the North Pole. Certainly, you know who Amundsen is.” Based on the above excerpt, it is evident that in his day – the early 20th century – Amundsen was clearly a celebrated figure on both sides of the Atlantic. Similarly, this correspondence also reflects the misinformation that the world had up until the time that Amundsen’s voyage was already underway, regarding the North Pole being his goal. Perhaps it is also worth mentioning that Amundsen is among the very few famous Gentiles I have encountered in my readings and translations over the past nearly 20 years. I suppose that that in itself speaks loudly for this man’s monumental – albeit unfortunately, little remembered – achievements.  Undated photo of Symon Petliura (1879-1926) (courtesy of Wikipedia: https://goo.gl/jf7Xme, accessed 2-3-17). Undated photo of Symon Petliura (1879-1926) (courtesy of Wikipedia: https://goo.gl/jf7Xme, accessed 2-3-17). 2) Symon Petliura (1879-1926) – Unlike Amundsen, Petliura established a highly negative reputation for himself among Jews, Poles, Bolsheviks, and other political and ethnic groups. It is Petliura, General Secretary of Military Affairs of the Ukrainian People's Army – or at the least, his military forces – who is credited for instigating many of the anti-Jewish pogroms that accompanied the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the ensuing Russian Civil War. According to death counts at the time, “it was estimated that at least 30,000 Jewish men, women and children were massacred in Ukrainian towns by Petlura’s forces” (Jewish Telegraphic Agency, May 27, 1926, accessed 2-2-17). Ultimately, Petliura was assassinated by a Jewish anarchist and Yiddish poet named Sholom Schwartzbard (1886-1938) on May 25, 1926, while strolling in Paris. Schwartzbard purportedly committed this act to avenge the murders of all his close family members during the pogroms of 1919-1920. Schwartzbard was acquitted by a Parisian court, and the murder trial – a cause célèbre of its day – emerged as a political case against the Ukrainian government. Today, Petliura is honored and remembered by the Ukrainian people as a national martyr and hero – one of their leading modern-day freedom fighters. As for Schwartzbard, he was aided by Jews the world over for what many of them considered an act of true heroism and justice. A committee was even formed for this very purpose in Chicago, aptly named the “Sholem Shvartsbard komitet” (or “Sholom Schwartzbard Arrangement Committee”). Indeed, it was this same committee that published Schwartzbard’s two autobiographical works in Yiddish: In krig mit zikh aleyn (“At War with Myself”) (1933) and In’m loyf fun yorn (“Over the Years”) (1934). This controversial, so-called modern-day avenger of justice for Jews, died on March 3, 1938 in Cape Town, South Africa while on a trip to raise funds for the publication of a Yiddish encyclopedia. As per his will, he was later reinterred in Israel. The Shalom Schwarzbard Papers, 1917-1938, may be accessed today at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York City.  Images and police paperwork of Sholom Schwartzbard (1886-1938) at the time of his assassination of Symon Petliura, Paris, France, 1926 (courtesy of Russia House News: https://goo.gl/ld6Wp5, accessed 2-7-117). Images and police paperwork of Sholom Schwartzbard (1886-1938) at the time of his assassination of Symon Petliura, Paris, France, 1926 (courtesy of Russia House News: https://goo.gl/ld6Wp5, accessed 2-7-117). The following is but a brief excerpt regarding Petliura’s pogromist bands, which I translated from Sefer Burshtin (“The Book of Bursztyn”), the memorial book of a town that is located today (c. 2017) in the Ukraine: During the years 1917-18, at the end of the First World War, fights continued for a long time between the Ukrainians, Poles, and Bolsheviks in the Bursztyn area. Because of its strategic placement, Bursztyn sustained a key position. It is clear that the scapegoat was always the Jewish population. Everybody tore pieces from them. Whichever army went through there robbed and raped Jewish women, filling the town with wailing. The women were raped in the presence of their husbands, parents, and children. The most heavily felt in the town were the Petliura-ists. Jewish life was utterly abandoned. In the pogroms and rapes there was participation both by the Ukrainian peasants and the intelligentsia, who demonstrated the lowest degree of animalism and sadism (pp. 147-148).  Mendel Beilis (b. Russian Empire, 1874-d. United States, 1934) (courtesy of the Forward, Dec. 18, 2013: https://goo.gl/lDT1iY, accessed 2-3-17). Mendel Beilis (b. Russian Empire, 1874-d. United States, 1934) (courtesy of the Forward, Dec. 18, 2013: https://goo.gl/lDT1iY, accessed 2-3-17). 3) Mendel Beilis (1874-1934) – A contemporary of the aforementioned noteworthy figures, Beilis is yet another name that has crept into the texts that I have translated. Without going into the elaborate details about him or his trial, suffice it to say that he was at the center of yet another cause célèbre, like Sholom Schwartzbard. However, in Beilis’ case, he was unquestionably a martyr, wrongfully accused of murdering a 12-year-old Andrei Iushchinskii in Kiev. The claim at the time by anti-Semitic hordes, members of the then Czarist government, and other members of Russian society, was that this was a typical case of blood libel that Beilis had perpetrated against an innocent Christian youth. Short of revisionists and anti-Semites, I would contend that there has been unanimous agreement among scholars, journalists, and laypersons in the West, that Beilis was scapegoated for an act he never committed. The reason being, was because he happened to live and work close to where the murdered boy was found. Moreover, Beilis was the only known Jew in the vicinity. This was the key point of significance, given the highly anti-Semitic regime and atmosphere that existed at the time in Czarist Russia. Beilis was arrested shortly after the victim’s body was discovered, and he languished in a squalid prison cell for over two years. His court case – by all accounts a kangaroo trial – took place in Kiev and lasted from September 25 through October 28, 1913. Thankfully, Beilis was finally acquitted of the crime, though the so-called Jewish institution of blood libel was not deemed to be fallacious. At the time, Beilis’ fate was documented in numerous newspaper articles and featured in many postcards. The international Yiddish press was certainly included among those periodicals and ephemera. In the aftermath of the acquittal, Beilis and his family tried to settle in Palestine, but ultimately immigrated to the United States. There, he wrote a memoir about his experiences in 1925, entitled (in Yiddish), Di geshikhte fun mayne layden (“The Story of My Sufferings”). The royalties of the book – which was also translated into English – helped sustain Beilis and his large family financially during his final years. Beilis died unexpectedly in Saratoga Springs, New York on July 7, 1934 and was buried in the same cemetery in Queens, New York, as the renowned Yiddish writer, Sholem Aleichem (1859-1916).  Di geshikhte fun mayne layden (“The Story of My Sufferings”) (1925) by Mendel Beilis (courtesy of the National Yiddish Book Center: https://goo.gl/HyvbHS, accessed 2-3-17). Di geshikhte fun mayne layden (“The Story of My Sufferings”) (1925) by Mendel Beilis (courtesy of the National Yiddish Book Center: https://goo.gl/HyvbHS, accessed 2-3-17). The following is a terse, but highly revealing excerpt from a family letter I recently translated from the Yiddish. The author’s words patently convey that emotions ran high – particularly among Eastern European Jews – during Beilis’ trial. Up until his acquittal, there was always the much warranted fear that Beilis would be found guilty and made to suffer the consequences of such a conviction. Written by Dawid Srebnagóra, in Płońsk, Russian Empire only one day before Beilis was found innocent – to various family members: Płońsk October 27, 1913 p. 3 When I returned home from Płock, I became seriously ill. I made use of doctors and medications. I had recited blessings for Beilis’ procurator. I am now taking a pen in my hand for the [very] first time, and my hand is still shaking. When I read the above words, I initially did a “double take” on the surname mentioned here, and then set out to confirm that this was indeed a reference to Mendel Beilis. I was somewhat stunned (though my hands were not quite shaking) to learn that this letter was written only a matter of hours before Beilis’ long-awaited acquittal and freedom. These are only a smattering of the larger body of famous and not-so-famous names I have encountered in the texts that I have read and translated over the years. Some of the other names that I will mention only in passing, are: Golda Meir (1898-1978), Israel’s first and only female Prime Minister to-date; and the Bielski Brigade, a network of Jewish partisans led by members of the Bielski family of Nowogródek, Poland, from 1942 to 1944 in Western Belarus. They singlehandedly succeeded in rescuing more than 1,200 Jews from an almost certain death. The Bielski Brigade entered the public sphere only as recently as 2009, in the film, Defiance, based on Nechama Tec’s book, Defiance: The Bielski Partisans (1993). I look forward to the diverse and many-faceted personalities I will surely encounter in my future translation assignments. Furthermore, I hope to have the opportunity to share those additional Yiddish translator’s discoveries with you, my readers. Should you have any documents pertaining to famous or not-so-famous individuals, or any other materials that you would like translated from the Yiddish, please do not hesitate to contact me at: rivka@rivkasyiddish.com. My clients often ask me about the type of themes and subject matter that I encounter in my unusual line of work. In the nearly twenty years since I began translating Yiddish texts, I have definitely found certain themes that are relatively common and widespread among family letters, in particular. In thinking this over recently, I was able to break down those frequent topics of correspondence into the following general groups: 1. Shortages of money and/or food – This is especially prevalent in letters written in Eastern Europe during times of economic depression, and/or warfare (e.g., World War I and II). Since many of the letters I encounter stem from the interwar period, I can say without question that these hardships become increasingly pronounced during the final years and months leading up to The Second World War. In certain instances, this coincides quite blatantly with the anti-Jewish laws that were enacted against Jews in large swaths of Eastern Europe. 2. Instructions regarding maintenance of the family business – Be it about business conducted in Europe (the proverbial “Old Country”) or already in the United States, South America, Palestine – “Eretz Yisrael” – or elsewhere (the proverbial “New Country”), this is a theme that frequently repeats itself – generally between fathers and sons, brothers, and other male family members. Only in rarer instances have I seen female family members included in these financial discussions. 3. Hope that the family will soon be reunited in the “New Country.” In the current state, the family is fragmented, divided between different continents – the “Old Country” versus the “New Country.” Occasionally this division is simply between different cities within the “Old Country.” It is entirely common to find the “Almighty’s” name invoked here. Many parents and grandparents (and other family members) often write something akin to: “I hope that the blessed Lord will help me in seeing you in-person, once again.” Sometimes the invocation is even more dramatic and imploring: “May I still lay eyes on you one last time before I depart this earth.” 4. Illness and death – References to family tragedies and misfortunes are not wholly uncommon. Usually these subjects are mentioned in conjunction with the worsening physical state of a parent or grandparent (or other close relative) and/or news of his/her untimely death. Sometimes this is clearly linked to the generally nefarious condition for Jews in Eastern Europe prior to (and leading into) the Holocaust. At times, when the letter is directed at a son, he is entreated with the responsibility of saying Kaddish (the Jewish prayer for the dead) and observing the seven-day period of Shiva (the time allotted within traditional Judaism for mourning). Traditionally, it was the obligation of the son/s to recite Kaddish for a year following the death of a parent. 5. Maintenance of religious traditions, primarily in the migration from the “Old Country” to the “New Country.” It was well-known that America, in particular, was not so much the proverbial “Goldene Medine” (Golden Land) - referenced by the likes of Jewish immigrant writers such as Anzia Yezierska (1880?-1970) in Hungry Hearts and other related works. Rather, for many Jews, America represented the “Treyfe Medine” (Unkosher Land) – at least for those Jews who continued to adhere to traditional, religiously observant Judaism. This realization on the part of Jews who remained behind in the “Old Country” regarding the decline of religious observance set in as early as the turn of the previous century. What’s more, it lasted right up until the outbreak of World War II. This is reflected in several letters that come to mind from the interwar period, usually written by admonishing parents to their children who had already immigrated to the “New Country” (mostly, from the letters I have translated, the United States).  “New Country”: Scene of the Lower East Side of New York City, turn of the 20th Century. Note that none of the adult males depicted here – many, if not all of them, likely Jewish immigrants – have beards, a typical mark of a religiously observant adult Jewish male. Also note that in many cases, business and shop signs bear Yiddish advertisements (sometimes, without the accompanying English translation). (Courtesy of the Tenement Museum New York: goo.gl/1Ob7Xw, accessed 12-31-16.) Anecdotally speaking, I will never forget a vignette my grandfather related to me vis-à-vis the perceived decline of observant Judaism in the “New Country,” in contrast with that of the “Old Country.” According to my grandfather, who was born in Kielce, Poland in 1904 – prior to such historical events as the sinking of the Titanic (which my grandfather recalled) and World War I (which, for some reason, my grandfather never mentioned to me) – there had been a local Jew in his community who had actually “gotten out” before World War II (my grandfather’s words) and come to America. Yet unbelievably, he returned to Kielce sometime during the interwar period, because as he informed the local Jewish community, it was impossible to maintain one’s “Yidishkeyt” (observance of traditional Judaism) in the “New Country,” as it was entirely “treyf” (unkosher). Cases in point of this growing religious divide between the older generation in the “Old Country” and the younger generation in the “New Country” may be seen for example, in some of the entries in the Forverts' /Yiddish Forward’'s advice column, known as “Dos Bintel Brief.” The column, which in Yiddish, literally means “The Bundle of Letters,” ran for over 60 years (from 1906 until at least 1970), and doled out various forms of advice regarding the struggles and woes of Jewish “greenhorns” – and their offspring – in the United States. The following abbreviated excerpt is but one such case highlighting this very divide: 1908 Worthy Editor, I have been in America almost three years. I came from Russia where I studied at a yeshiva. My parents were proud and happy at the thought that I would become a rabbi. But at the age of twenty I had to go to America. Before I left I gave my father my word that I would walk the righteous path and be good and pious. But America makes one forget everything. Here I became an operator, and at night I went to school … entered a preparatory school, where for two subjects I had a Gentile girl as teacher… I don’t know what I would have done without her help. I began to love her, but with mixed feelings of respect and anguish … and I never imagined she thought of marrying me… Then she spoke frankly of her love for me and her hope that I would love her… I was confused and I couldn’t answer her immediately. In Europe I had been absorbed in the yeshiva … She is pretty, intelligent, educated, and has a good character. But I am in despair when I think of my parents. What heartaches they will have when they learn of this! I asked her to give me a few days to think it over. I go around confused and yet I am drawn to her. I must see her every day, but when I am there I think of my parents and I am torn by doubt… Respectfully, Skeptic from Philadelphia (A Bintel Brief, edited and with an introduction by Isaac Metzker. New York: Ballantine Books, 1972, pp. 77-78.) In contrast to the above categories, I may also add here – should the reader be wondering about themes that are scarcely discussed in the letters that I have translated – that I have a brief list, as seen in the following: 1. Serious financial corruption and fall-out within families; 2. Family members marrying outside of the Jewish faith; 3. Marital indiscretions, illegitimate births, abortions, and the like. Perhaps not surprisingly, this category, as well as the previous one, are typically referred to in rather euphemistic terms. I would like to focus on the last category of my most frequent themes in my current blog (“Maintenance of religious traditions”), as it is a subject that has appeared with greater recurrence in letters that I have translated recently. In order to shed further light on this phenomenon, I shall provide one excerpt here from some of these letters – to be continued (ideally) in my next month’s blog. However, in order to honor the privacy of my client, names have either been omitted or changed here. p. 1 With God’s help November 25, c. 1920s, Podgórze (Kraków) Dearest daughter, Lea, I received your letter today. Your words shook my heart, such that I could not calm down from crying. I had joy and suffering. For every word, I wished [you] well; that everything should always go well for you, and that my eyes should yet see you. For you recognize your sin. Therefore, the blessed Lord will forgive you; and I forgive you, as well. I am very glad that you are living a Jewish lifestyle. The blessed Lord will always help you… p. 2 …. And that which you write, that Rifke says that since you write, she need not also write … Were she still to have feelings toward her parents. But I see that her feelings have already been extinguished. The most significant thing is that she does not live a Jewish lifestyle, so she has no heart to write her parents. She must wrangle with the fact that nobody lives forever; not be [unduly] proud about her little house, seeing as her father had more than she has. And she did not take anything with her, now that she had an opportunity to do penance [i.e., for the sins/wrongdoings she did to her parents and in not living a Jewish lifestyle] and left it to you [i.e., that “you” should be responsible for writing, since she has no heart to do so]. Thus, I do not envy her. As I learned from my client regarding the above excerpt, which I translated from a larger body of text, the author of this letter was a very pious woman. Several of her children were already living in the United States at the time when she wrote these words to one of her daughters. The author, known by her descendants as “Bubbe [Grandmother] Dina,” was quite adamant that her children maintain their religiously observant lifestyles – regardless of whether they were now living in a more “open” and less Jewish environment overseas. What disturbed her most, though, as my client related, was that one of her daughters – Rifke – had decided to marry a man who was not religiously observant. The family’s oral tradition was that Rifke had always been “the rebellious child” – the one who had distanced herself from the rest of the family, stopped observing the Jewish Sabbath, keeping kosher, and the like. As such, my client was not in the least bit surprised to read (in translation) these admonishing words of “Bubbe Dina” regarding Rifke’s not living a “Jewish lifestyle.” The above letter excerpt – translated from the original Yiddish – is but a small window into the types of subject matter that I frequently encounter in my work as a Yiddish translator. In my next blog, I will pick up this subject again – and possibly some of the other themes I mentioned above. As one can see from the words expressed here, there was an evident growing divide – certainly along the lines of religious Jewish observance between the older and younger generations, even within close-knit families. This divide was all the more blatant when the older generation (that generally constituted the authors of the letters that I receive) still remained behind in the “Old Country” and the younger generation had already immigrated to the “New Country.” I would imagine that many of my readers are familiar with this phenomenon within their own families. As such, I invite you to please share you own accounts of this particular theme in your comments following my blog post. I am always interested in and intrigued by reading about such family “sagas” in my work as a Yiddish translator.  “New Country”: Delancey and Essex Streets on the Lower East Side of New York City, c. 1908. This was formerly one of the most prominently Jewish immigrant neighborhoods in all of New York. Faint Yiddish advertisements may be seen in the background. (Courtesy of Old NYC Photos: oldnycphotos.com: goo.gl/jr5agn, accessed 12-31-16.) Should you have any such family letters pertaining to any of the subject matter discussed here or beyond that you would like translated from the Yiddish, please do not hesitate to contact me at: rivka@rivkasyiddish.com.  “Old Country, New Country”: Illustration that may be interpreted to represent the stark contrast between the “Old Country,” as demonstrated by the lone traditional Jewish shtetl fiddler situated amidst the large and looming urban landscape of the “New Country” (in this case, New York City). (Courtesy of Timeline Touring: http://timelinetouring.com/images/fiddler.jpg, accessed 12-31-16.) Growing up in a family environment in which Yiddish was yet another vernacular spoken language along with English, I was exposed from a very early age to Yiddish songs and even nursery rhymes, which were generally sung to and by my younger siblings and me. Indeed, some of my earliest memories include dancing and singing along to records of Klezmer music that played on our record player. The songs amplified on that old and overworked record player included Yiddish language singers that were especially popular (and several of whom are still musically active today) in the early-to-mid-1980s – musicians and vocalists such as Henry Sapoznik of the then Klezmer ensemble, “Kapelye”; Chava Alberstein; Dudu Fisher; Mike Burstyn; Hankus Netsky of the Klezmer Conservatory Band; the late Barry Sisters; and the recently deceased, Theodore Bikel (1924-2015). It has been some time since I have heard those songs played with any regularity – and certainly not on a record player or tape recorder, for that matter – in our age of CDs, YouTube, and the like. However, in recently surfing the selections of Klezmer music available today on YouTube, I am reminded of specific songs that were once so familiar to me – and likely very familiar to many of my readers, as well: (and here, I am using the most commonly used orthography for these songs) “Rumania, Rumania,” “Mayn Shtetele Belz” (“My Small Town of Belz”), “Der Rebbe Elimelech” (“The Rabbi Elimelech”), “Papir iz Dokh Vays” (“Paper is Still White”), “Oyfn Veg Shteyt a Boym” (“On the Road Stands a Tree”), “Tumbalalaika” (“Play Balalaika”) and a host of others that are simply too many to include here. If you were to ask me which of these numerous songs I considered my favorite, I would be hard-pressed to answer you. It really depended on the given day and my particular mood at the time. And all these years later, I still feel exactly the same way.